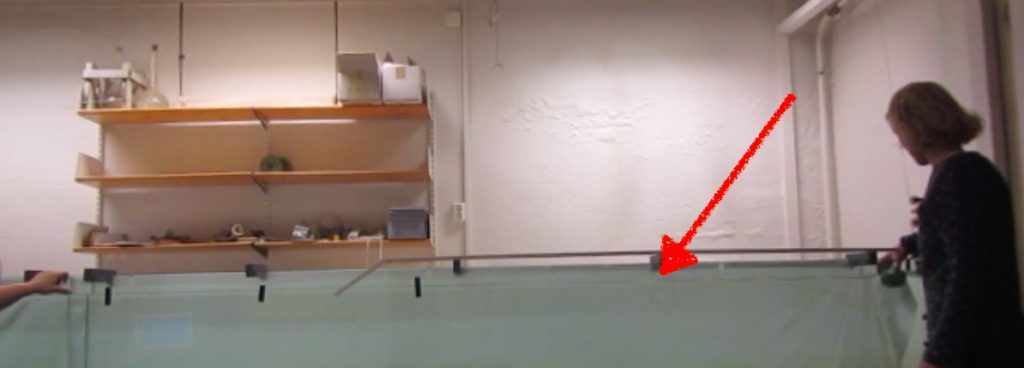

Hi, I’m Dan Wallace, a PhD student at the Institute of Sound and Vibration Research in Southampton, UK. I’m interested in lots of areas of acoustics — here I am working on a prototype 3D audio system in one of our anechoic chambers, as part of my Masters project.

Dan inside an anechoic chamber. Photo credit: Dan Wallace/University of Southampton

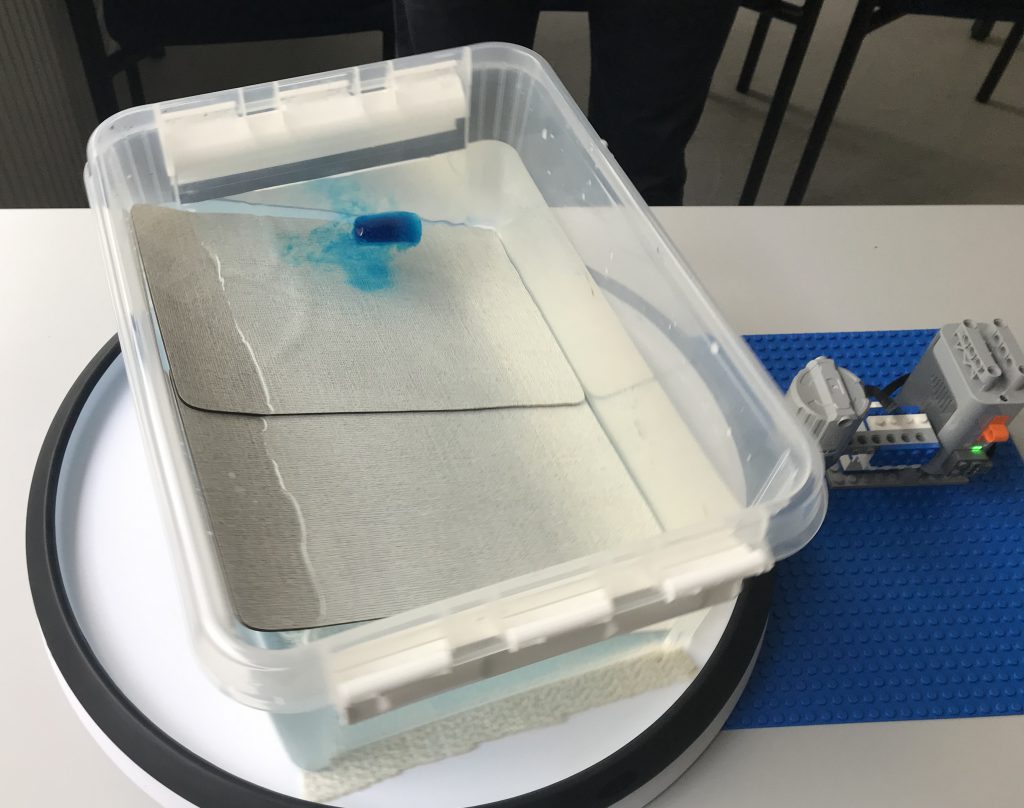

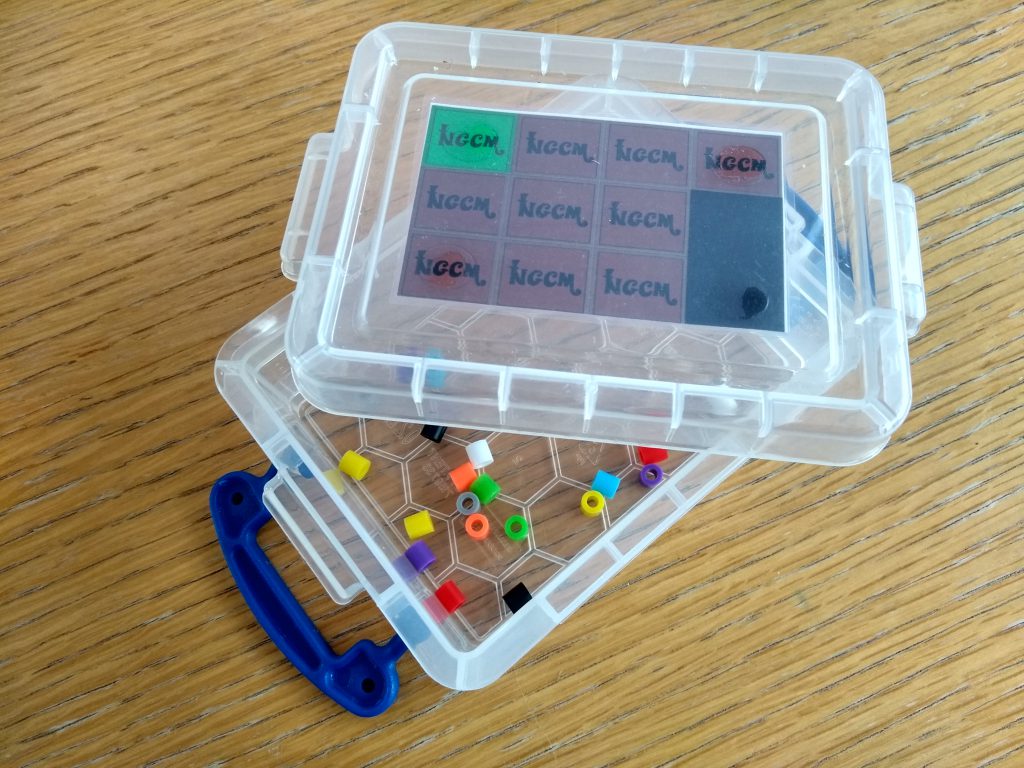

Today though, I’d like to talk about a machine I’ve designed, the CHocolate Oriented Machine-learning Processor (or CHOMP for short). CHOMP is a machine learning system designed to play a table-top game to super-human levels, with no silicon chips, no neural networks, not even any electricity… Introducing CHOMP!

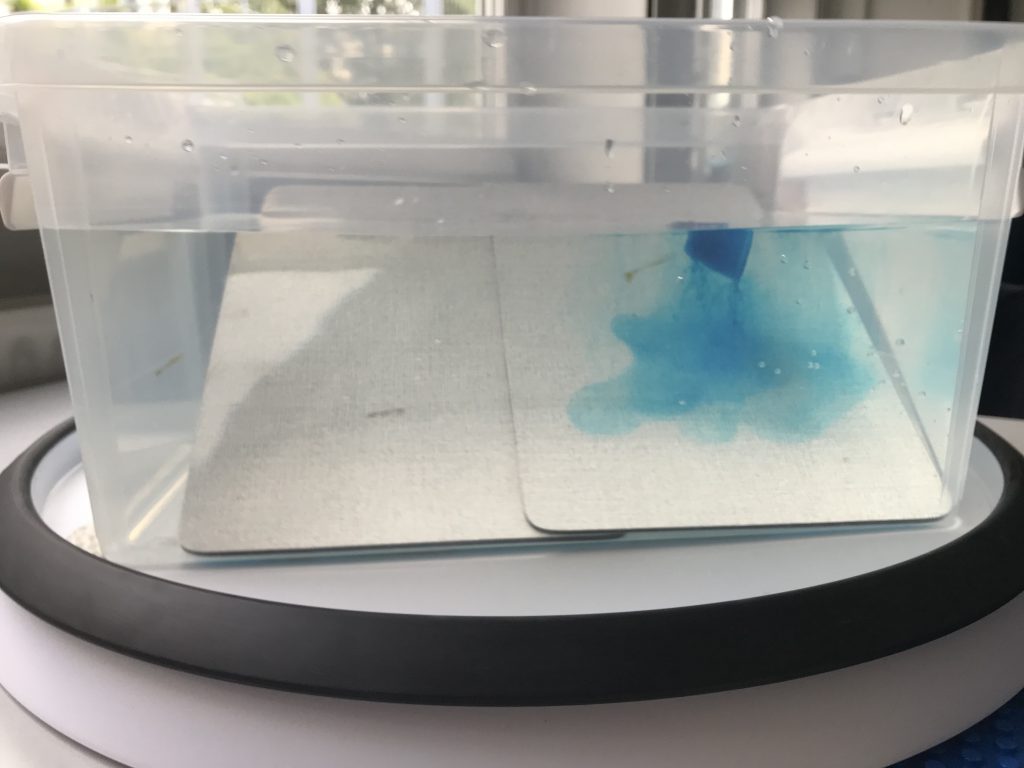

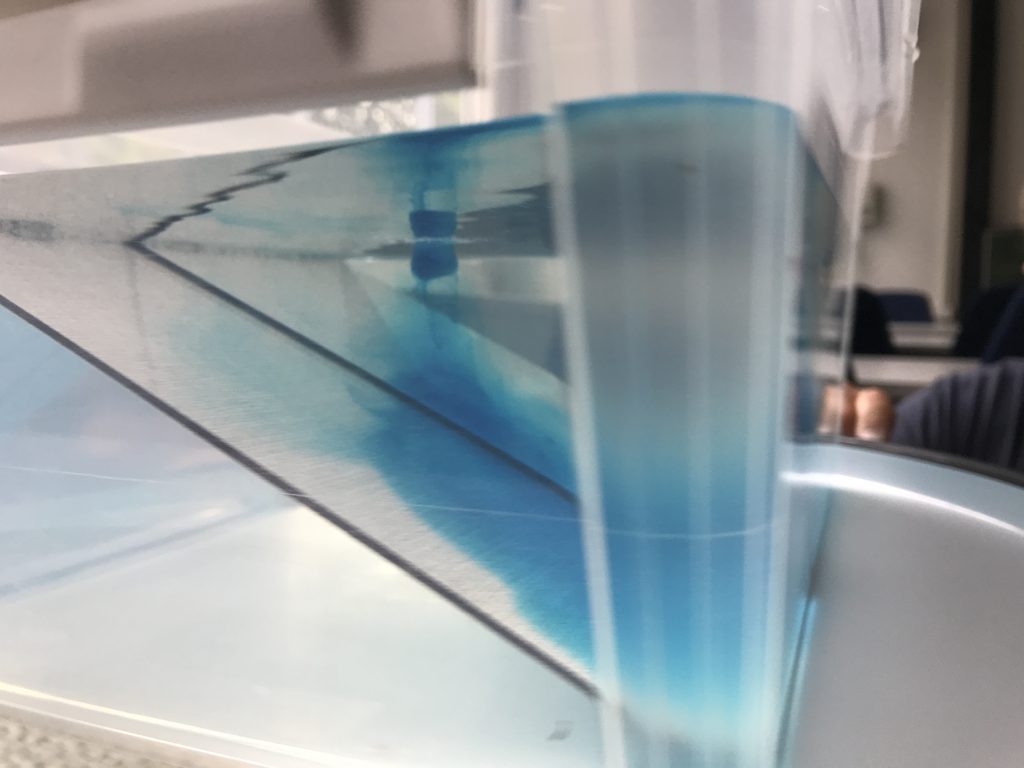

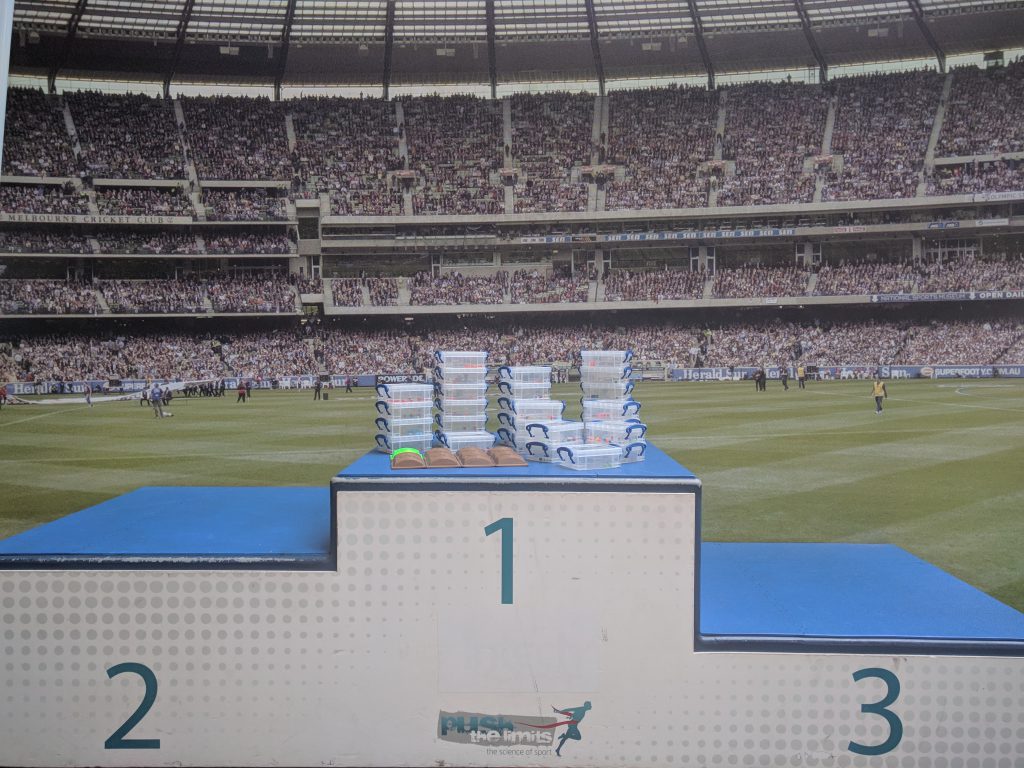

Chomp’s hardware: A bunch of plastic boxes. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

This pile of plastic boxes has triumphed over PhD’s, employees of Google DeepMind, numerous seven-year olds and our University Vice-Chancellor – all it takes is a little training.

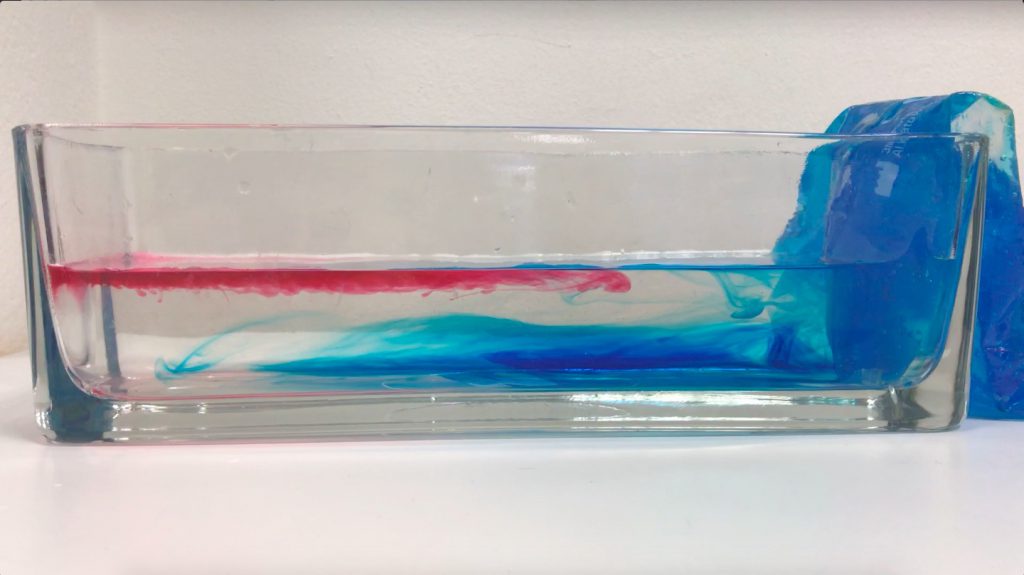

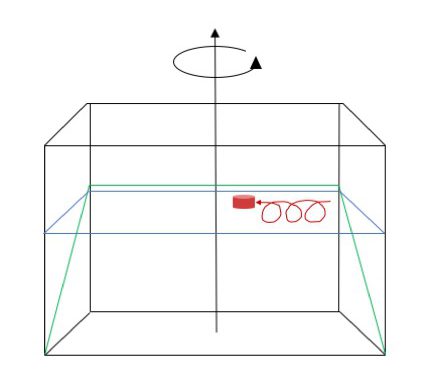

First, let’s introduce the game we’re playing. Like all the best games, our game is played with a big bar of chocolate, but for sustainability (of our waistlines), ours is 3D printed. By the way, NGCM stands for Next Generation Computational Modelling. NGCM is the Centre for Doctoral Training who are supporting me throughout my PhD with training, equipment and funding.

3D-printed chocolate bar. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

Players alternate taking bites out of the bar of chocolate from the bottom right corner, and the aim of the game is to avoid the poisoned square in the top left corner. Bites can be as big as you like, provided you follow one simple rule: Pick a square, remove it, then remove all squares below it and to the right.

A game of chomp. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

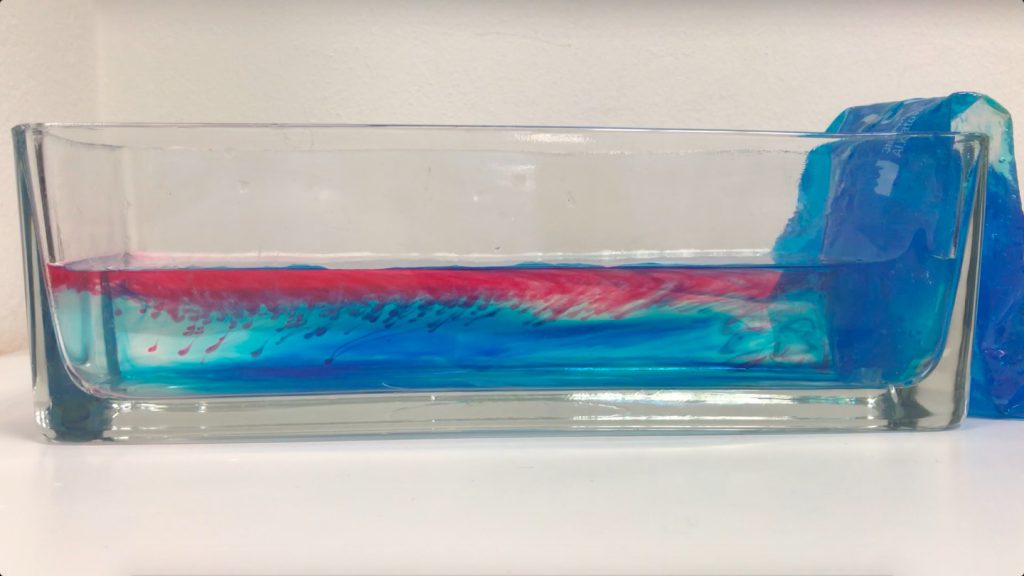

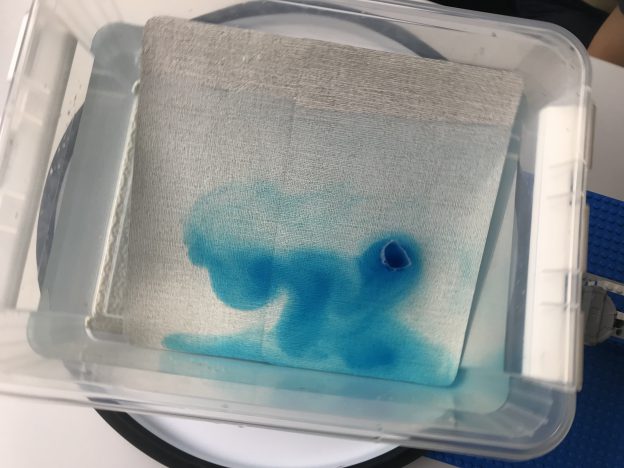

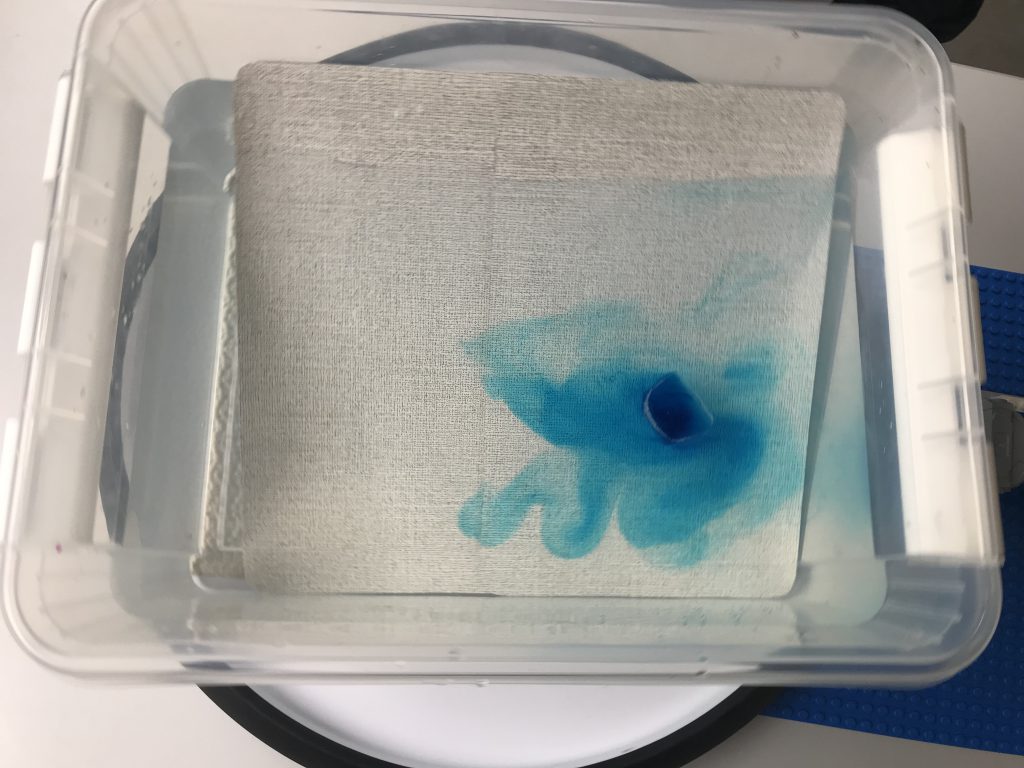

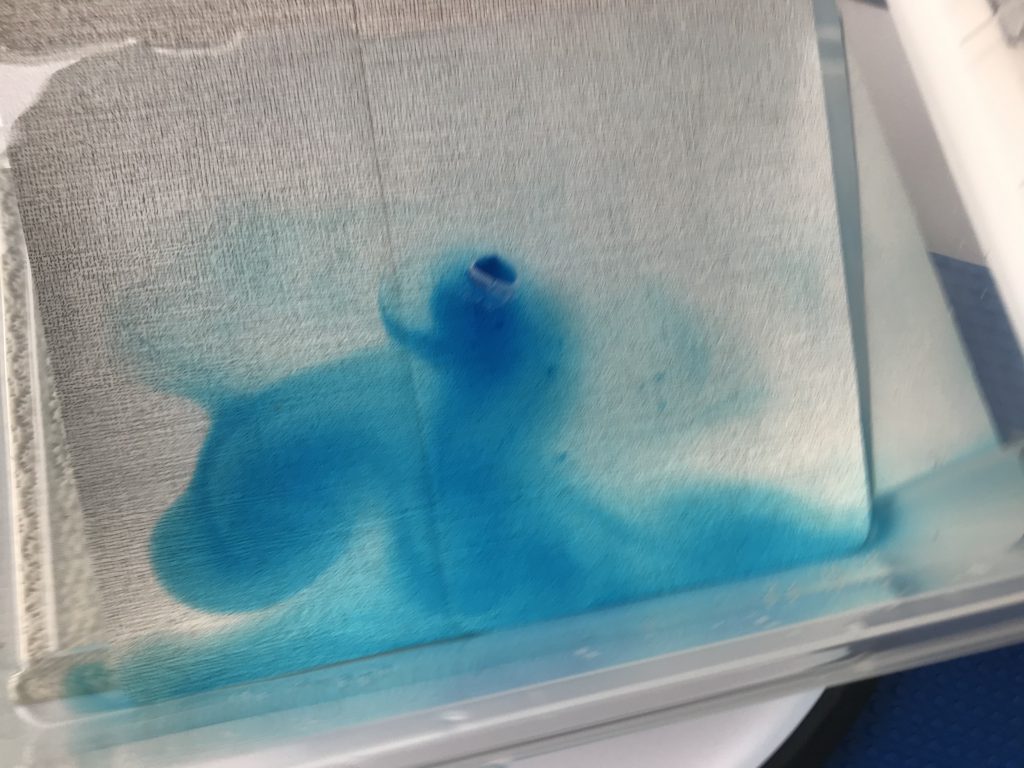

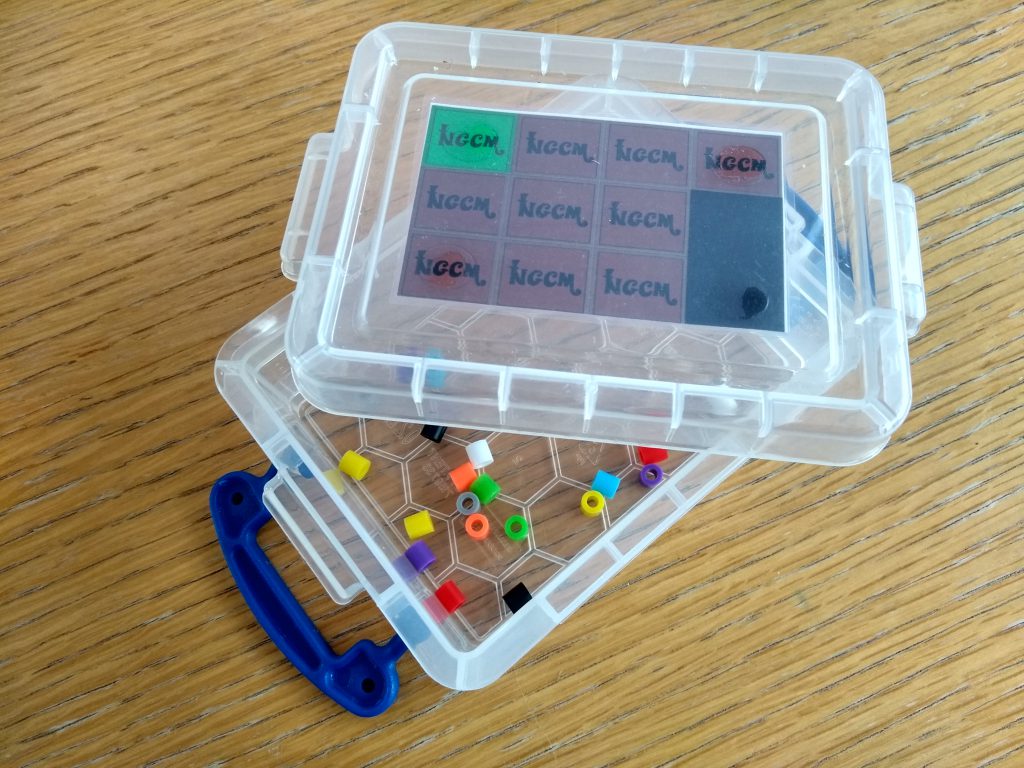

Let’s look a little closer at CHOMP to see how the machine makes decisions. Each of the 33 boxes which make up CHOMP is labelled with a picture of the chocolate bar in a different state, and in every box are some coloured beads.

A glance inside the inner workings of Chomp: one of Chomp’s plastic boxes with colored beads inside. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

Each different coloured bead represents a different sized bite out of the chocolate bar – remember the rule: Pick a square, remove it, then remove all squares below it and to the right. When playing against people, we provide a handy map to show which coloured bead refers to which square. CHOMP lacks the dexterity to choose moves for itself, so we let players help by picking a bead at random from the correct box.

Which color bead corresponds to which move? Photo credit: Dan Wallace

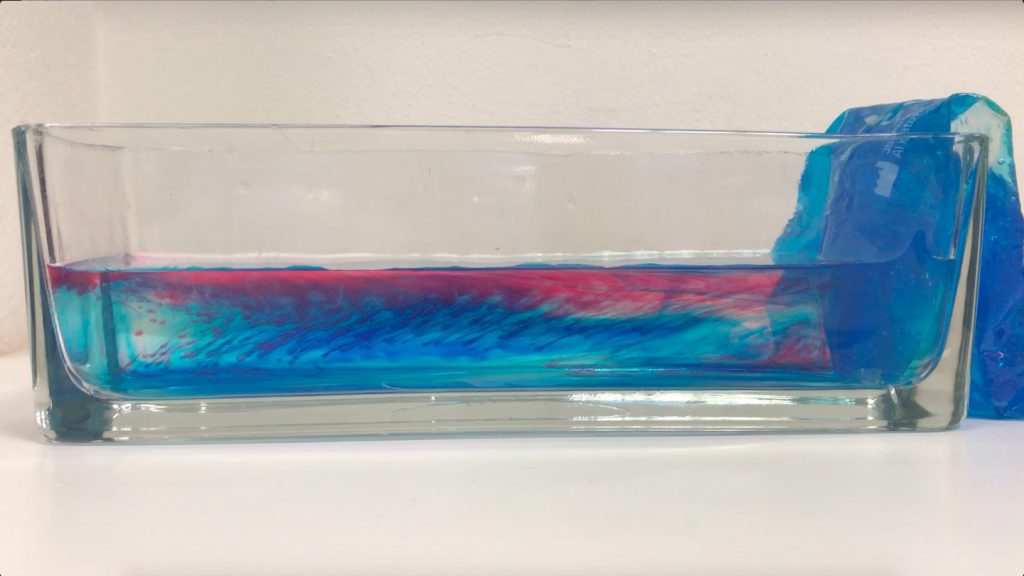

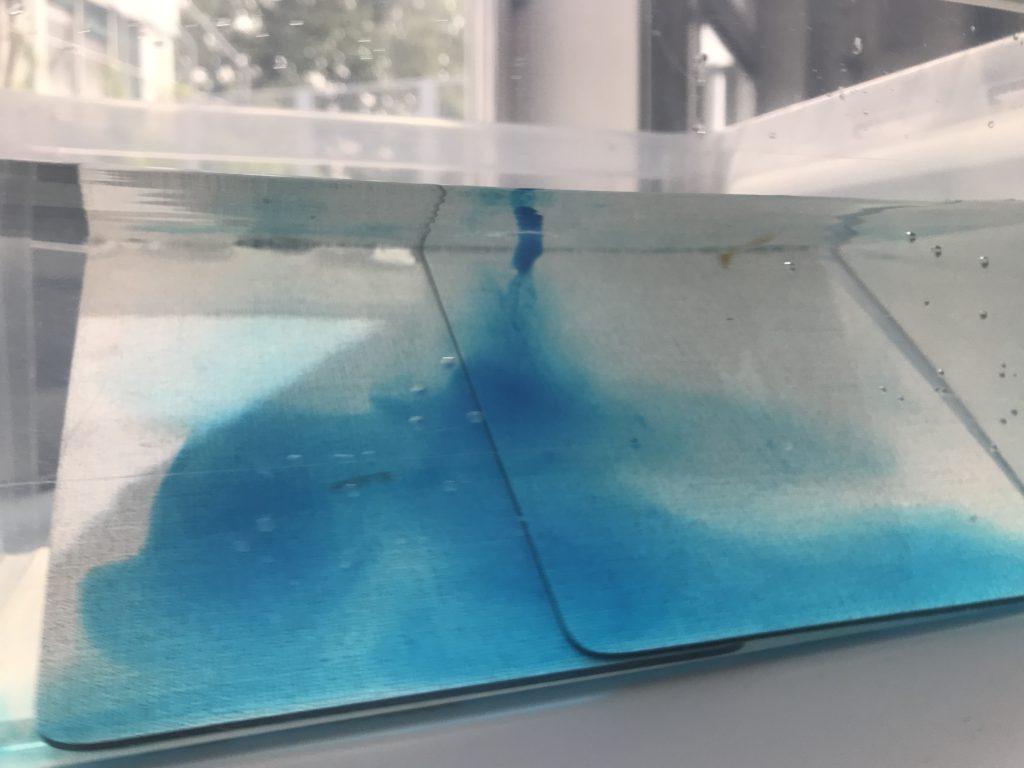

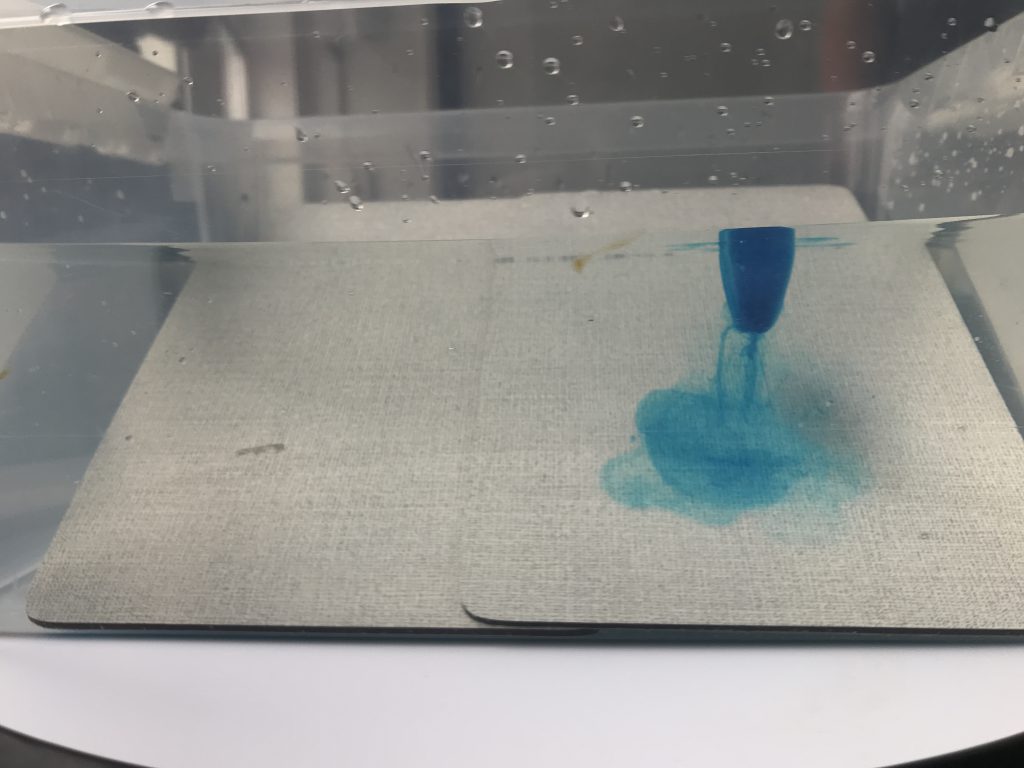

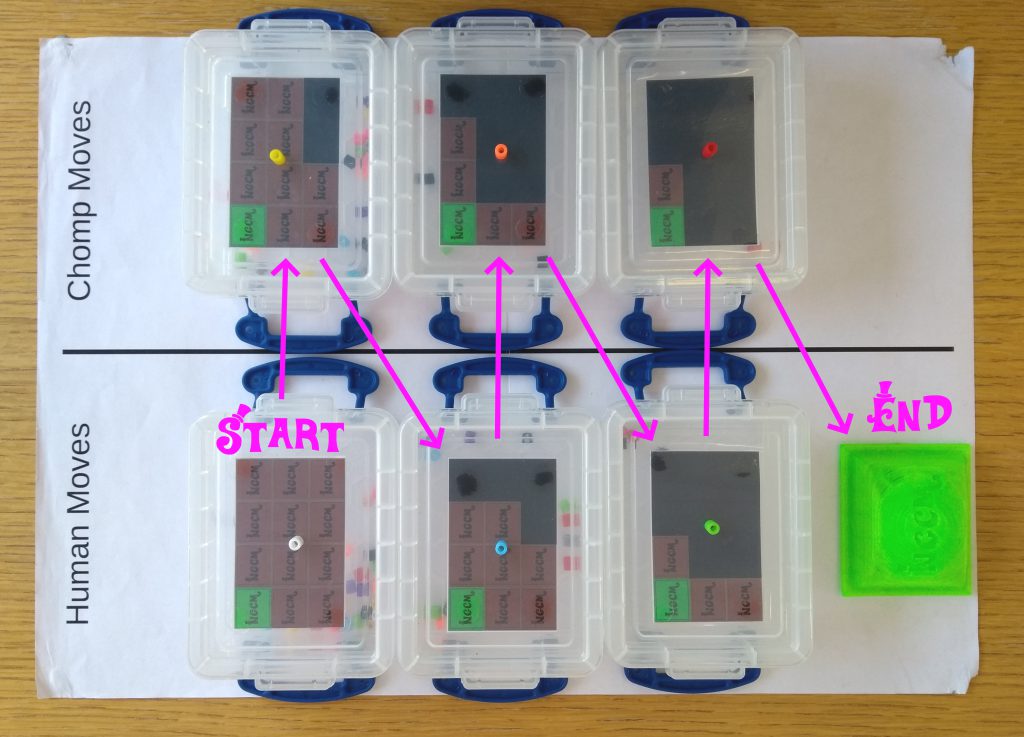

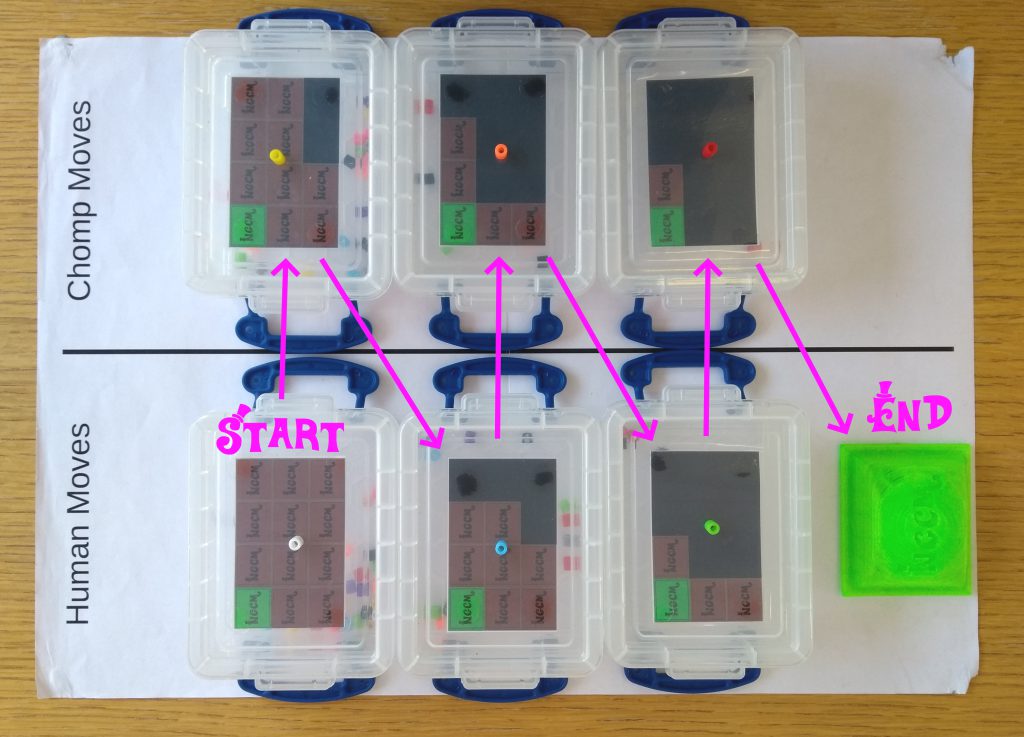

As we play the game, we record the moves which are played by each player by placing the chosen bead on top of the box it came from. At the end of the game, we have two lists of moves, one of which ended in a loss (in this case, made by the human) and another which ended in a win (for CHOMP!)

Documenting a single game of Chomp. Displaying the moves that got chosen by the human and “the machine”. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

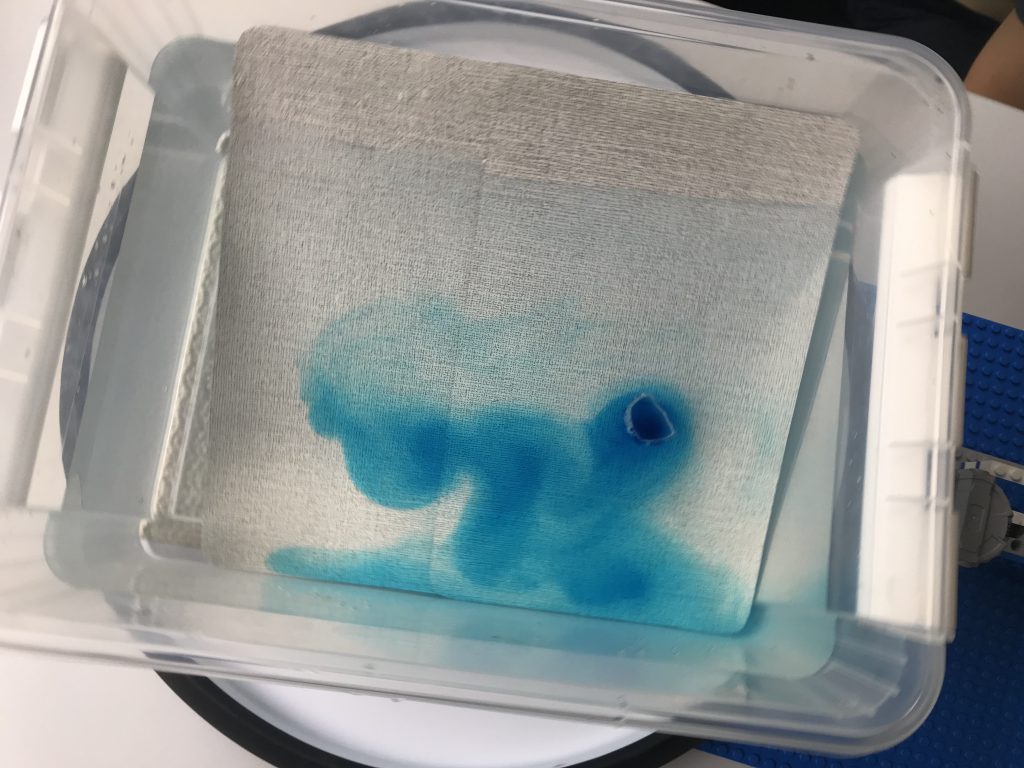

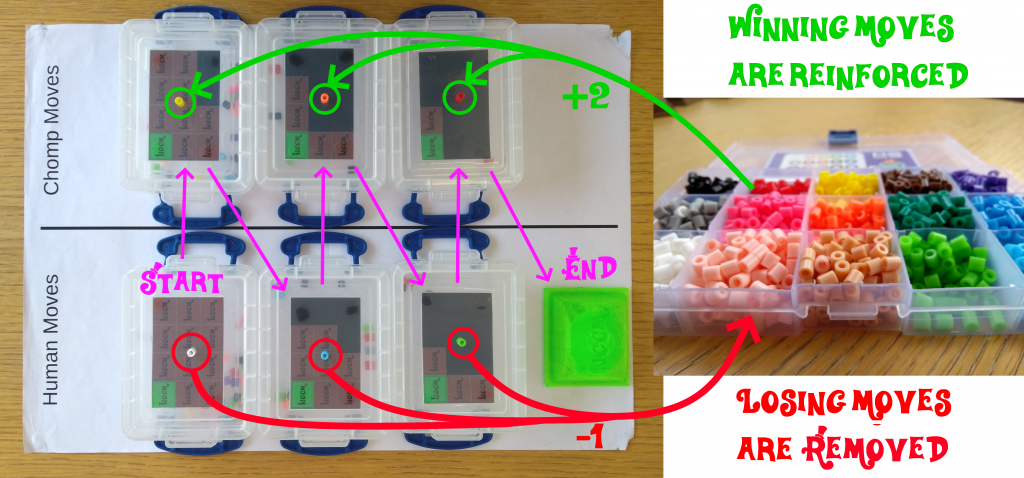

This information about good and bad moves enables us to train the machine.

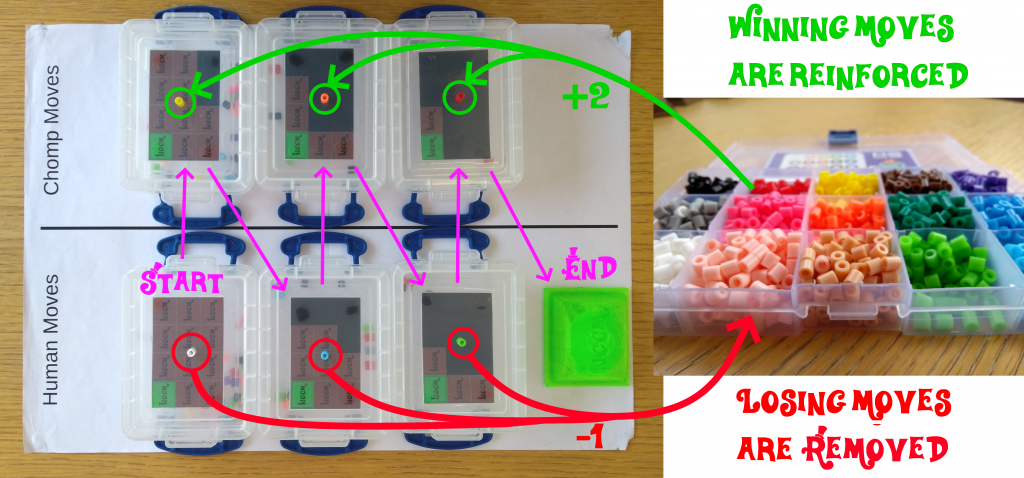

Every losing move is removed from the game, decreasing the probability that CHOMP would choose that move, from that position, in the next game. Every winning move is returned to its box, with two extra beads, increasing the probability that CHOMP will make good moves. Through this process alone, called “Reinforcement Learning”, CHOMP learns the winning strategy.

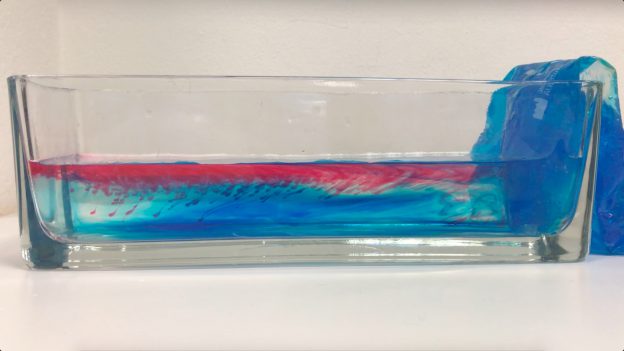

Winning moves are reinforced by adding more beads the color of the winning move. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

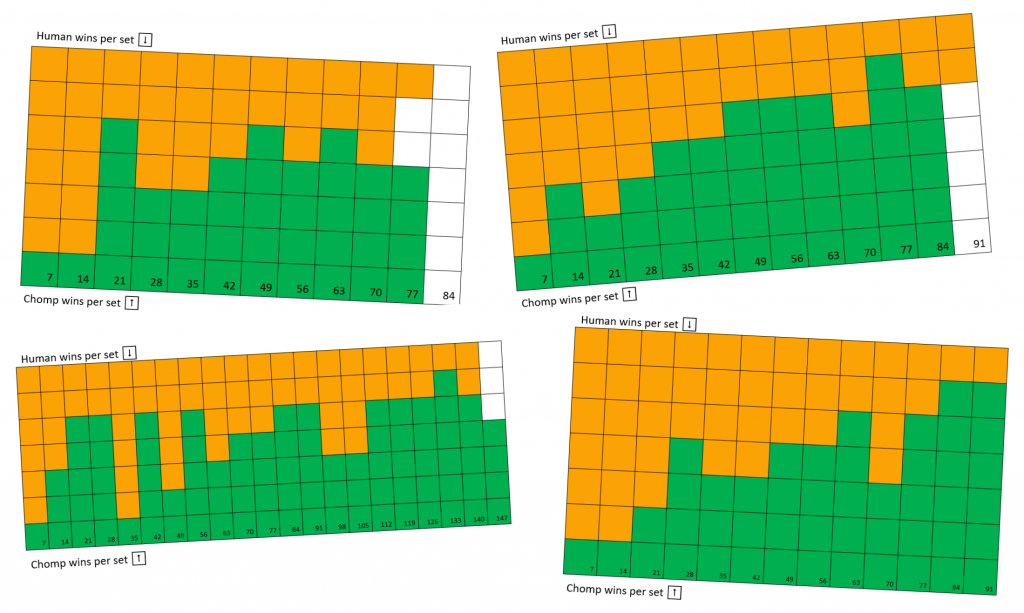

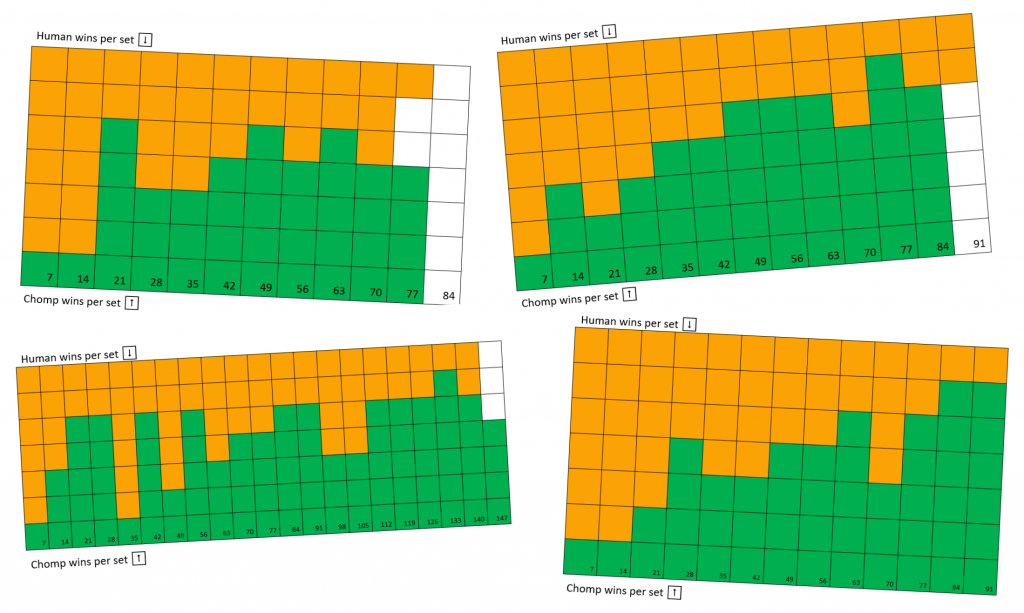

And it works! We have recorded every game we’ve played with CHOMP since spring of 2018, marking games off in sets of seven. Human wins are marked in orange from the top of a set, and CHOMP wins are marked in green from the bottom. At the start of each tournament (the leftmost column in each chart) we reset CHOMP so that every bead in each box is equally likely to be chosen. The results show that while CHOMP might win a game by chance, six times out of seven, humans win. Over time though, CHOMP gets stronger and stronger, winning five or six games out of seven after around 70 games worth of training.

Documenting how the probability of winning against Chomp decreases the more Chomp has been trained. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

We usually give our opponents a Cadbury’s Chomp bar as a prize for beating the machine. If they lose, we still give them chocolate as a thank-you gift for helping to train up CHOMP. We are #notsponsored by Cadbury’s yet!

If you are lucky you win a Cadbury bar when winning against Chomp! #notsponsored by Cadbury (yet?). Photo credit: Dan Wallace

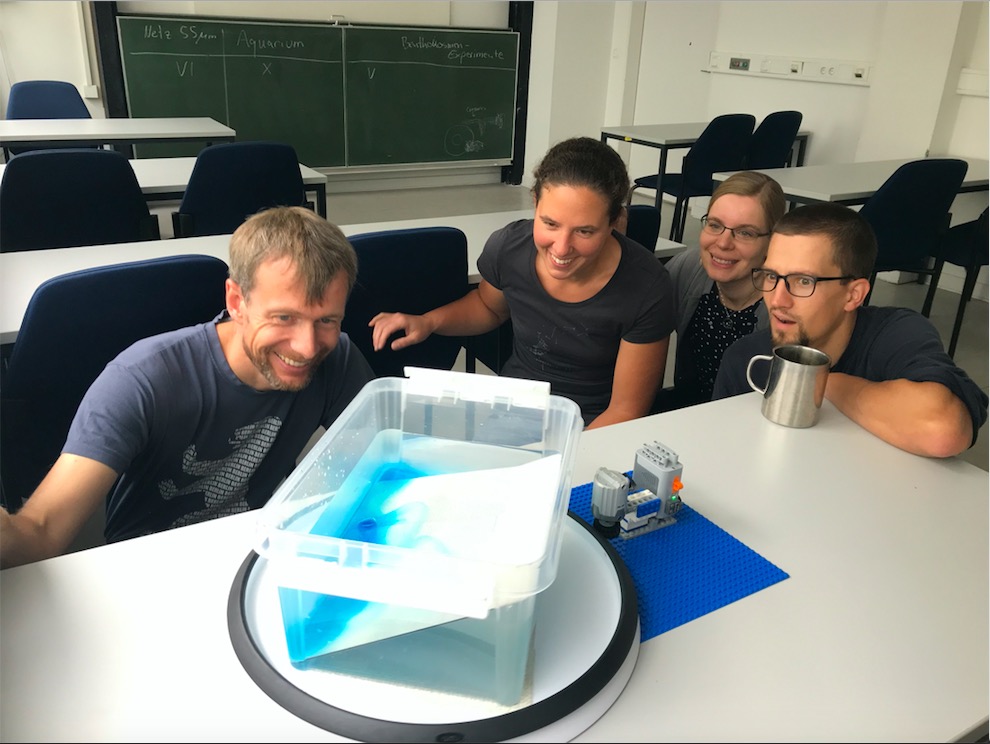

The beauty of CHOMP is that it is simple enough for a five-year-old to play, but powerful enough to surprise a professor. We’ve taken CHOMP to schools, science centres, university events and academic conferences, receiving some brilliant feedback from our defeated opponents. I’ll leave you with some quotes:

“So often, communication about AI and technology centres on the amazing tech, this game removes all that and shows how these machines operate beneath the algorithm!”

“Great presentation and concept. I loved seeing the “analogue” version of something so often thought of as digital!”

“Very interesting, it tears apart the fear of AI, because it’s just plastic boxes!”

Chomp on a winner’s podium. Photo credit: Dan Wallace

CHOMP is fully open-source, and instructions on how to make your own set can be found at www.github.com/dw-ngcm/chomp. If you’re running an event and you’d like CHOMP to feature, please contact me at D.Wallace@soton.ac.uk.