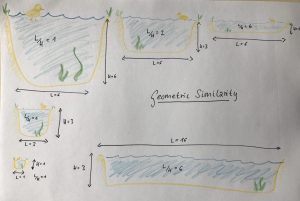

Tides themselves don’t induce (a lot of) mixing, only tides hitting topography do. An experiment.

As you might have noticed, the last couple of days I have been super excited to play with the large tanks at GFI in Bergen. But then there are also…