Finally published yesterday: “Student guides: supporting learning from laboratory experiments through across-course collaboration” by Daae et al. (2023)

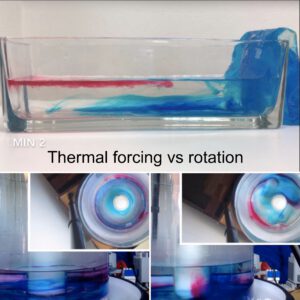

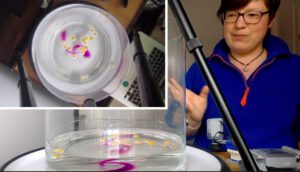

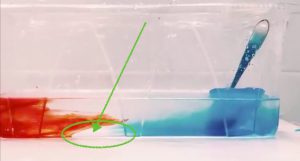

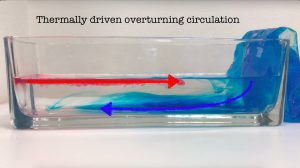

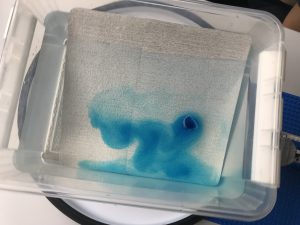

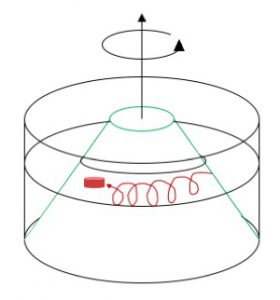

A project near and dear to my heart is using the DIYnamics rotating tank experiments in across-course collaborations. “Older” students, who did experiments the previous year, are trained to then…