This is a method that I have been excited about ever since learning about #birdclass in the “Evidence-based undergraduate STEM teaching” MOOC last year: Help students discover that the content of your class is not restricted to your class, but actually occurs everywhere! All the time! In their own lives!

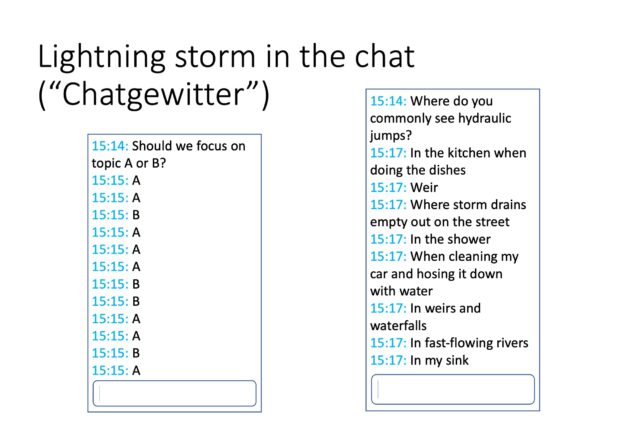

The idea is that students take pictures or describe their observations related to course materials in short messages, which are posted somewhere so every participant of the class can see them.

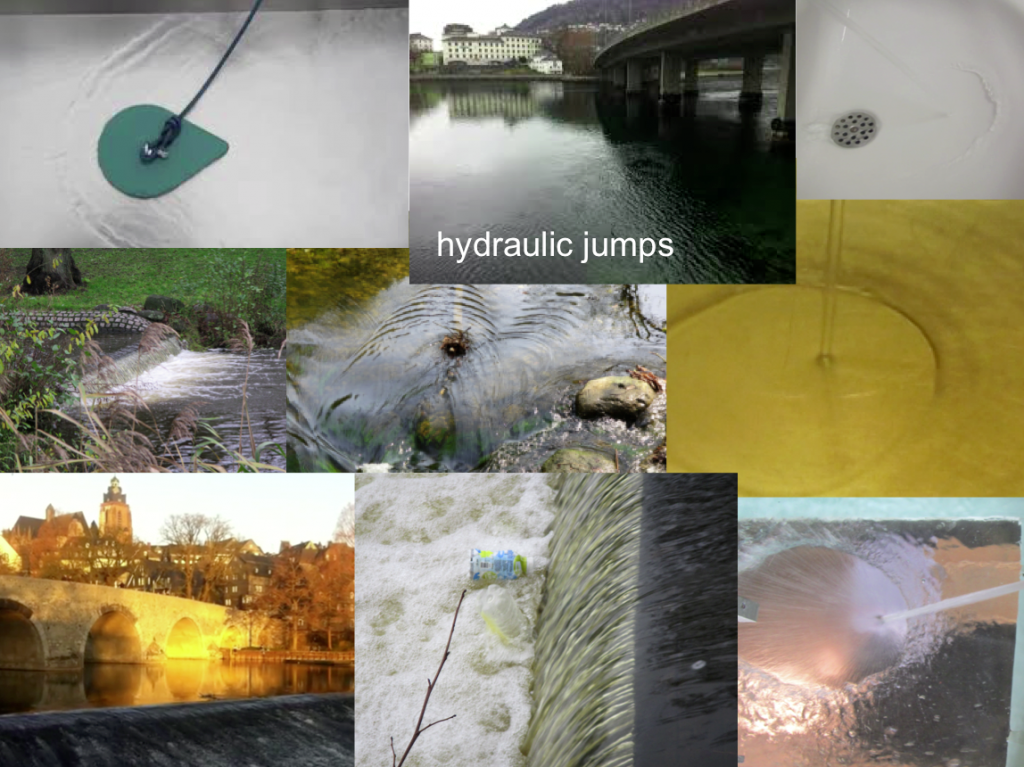

One example where I would use this: Hydraulic jumps. As I said on Tuesday, hydraulic jumps are often taught in a way that students have a hard time realizing that they can actually observe them all the time. Most students have observed the phenomenon, maybe even consciously, yet are not able to put it together with the theory they hear about during their lectures. So why not, in your class on hydrodynamics, ask students to send in pictures of all the hydraulic jumps they happen to see in their everyday life? The collection that soon builds will likely look something like the image below: Lots of sinks, some shots of people hosing their decks or cars, lots of rivers. But does it matter if students send in the 15th picture of a sink? No, because they still looked at the sink, recognized that what they saw was a hydraulic jump, and took a picture. Even if all of this only takes 30 seconds, that’s probably 30 extra seconds a student thought about your content, that otherwise he or she would have only thought about doing their dishes or cleaning their deck or their car.

A collection of images, all showing hydraulic jumps of some kind.

And even if you do this with hydraulic jumps, and not with Taylor columns or whatever comes next in your class, once students start looking at the world through the kind of glasses that let them spot the hydraulic jumps, they are also going to look at waves on a puddle and tell you whether those are shallow water or deep water waves, and they are going to see refraction of waves around pylons. In short: They have learned to actually observe the kind of content you care about in class, but in their own world.

The “classic” method uses twitter to share pictures and observations, which apparently works very well. And of course you can either make it voluntary or compulsory to send in pictures, or give bonus points, and specify what kind and quality of text should come with the picture.

You, as the instructor, can also use the pictures in class as examples. Actually, I would recommend picking one or two occasionally and discussing for a minute or two why they are great examples and what is interesting about them. You can do this as introduction to that day’s topic or as a random anecdote to engage students. But acknowledging the students’ pictures and expanding on their thoughts is really useful to keep them engaged in the topic and make them excited to submit more and better pictures (hence to find better examples in their lives, which means to think more about your course’s topic!).

And you don’t even have to use twitter. Whatever learning management system you might be using might work, too, and there are many other platforms. I recently gave a workshop for instructors at TU Dresden and talked about how awesome it would be if they made their students take pictures of everything related to their class. They were (legitimately!) a bit reluctant at first, because you cannot actually see the topic of the course, measuring and automation technology (MAT), just the fridge or camera or whatever gadget that uses MAT. But still, going about your everyday life thinking about which of the technical instruments around you might be using MAT, and discovering that most of them do, is pretty awesome, isn’t it? And documenting those thoughts might already be a step towards thinking more about MAT. At least that is what I claimed, and it seems to have worked out pretty well.

We are about to try this for a course on ceramics (and I imagine we’ll see tons of false teeth, maybe some knees, some fuses, many sinks and coffee cups and flower pots, maybe the occasional piece of jewelry ), and I am hoping they will relate what they take pictures of to processes explained in class (like sintering, which seems to be THE process in that class ;-))

I am going to try to implement it in other courses, too. Because this is one of the most important motivators, isn’t it? The recognition that what that one person talks about in front of the class all the time is actually occurring in – and relevant to – my own life. How awesome is that? :-)

Have you tried something similar? How did it work out?