Currently reading and thinking about Sustainability Communication

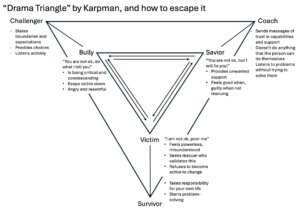

Yesterday, I talked to someone about Sustainability Communication and what we should be teaching our students, and I was honestly expecting something like the Karpman Drama Triangle (see featured image)…