Reposting a guest post I wrote for the @DIYnamicsTeam‘s blog:

When we came across the DIYnamics article right after its publication, Torge and I (Mirjam) were very excited about the endless possibilities we saw opening up with an affordable tool like the DIYnamics rotating table. We applied for, and were granted, money for an “innovative teaching” project by Kiel University’s PerLe (1) and built four DIYnamics rotating tables (five if you count the one I built for personal use ;-)), which we’ve been working with for about a year now. Since we are using them in a slightly different context than we’ve seen described before, and also have modified and added some of the experiments, I thought I’d report on it here. If you have any comments or suggestions for us, please do get in touch!

DIYnamics tables in undergraduate education

In contrast to using the DIYnamics rotating tables mainly for outreach purposes which is the most common application I am aware of, we are using them as part of a regular Bachelor-level class on “ocean and atmosphere dynamics” at Geomar, Germany. I have gained a lot of experience using a rotating table in undergraduate education at GFI, Norway, but there we only had one – much bigger – table available. Now we have four that can be used simultaneously! This is great for so many reasons:

Time efficiency for the instructor

With only one rotating table available, the typical setup I have used was to have small groups of students come in at different times over the course of a week or so, to do that week’s experiment with me. But that meant that I would spend a lot of time in the lab, and a large part of that time would be spent on waiting for the water on the rotating table to have spun up into solid body rotation, as well as prep time or cleaning, drying, putting away time.

Of course, wait times can easily be used for discussions of the upcoming experiment, of the concept of a “spun up” body of water, of how to judge whether or not a body of water is spun up or not, and many other things. But those are things that don’t necessarily have to be discussed in a setting of one instructor per each small student group, they could just as well be discussed in student groups and then in a larger plenum.

Exchange between student groups

In the setup with one table and student groups coming in one after the other, students would then write lab reports, submit them, and come back for the next experiment. While I am sure there was some exchange between student groups happening (which we could sometimes see from eerily similar ways of expressing things between groups, or errors propagating through several groups’ reports), that wasn’t an instructional design choice.

Now, however, when we have student groups working on the same experiment at the same time in the same room, it is very easy to have discussions both within individual groups and then across groups. There are many instructional methods to choose from that facilitate that kind of exchange, for example “think, pair, share”, where students first think about a question individually, then pair up with a partner (or the group at their tank) to discuss, and then results are shared with and discussed in the whole class.

Seeing many implementations of the same experiment

One reason why these discussions are especially fruitful if done in connection with simultaneously-run tank experiments is that, even if all student groups get the exact same instructions, two implementations of the same experiment do not ever look the same. There is always something that’s different. Maybe one tank is spun up less than the others, or a bit wobbly, because someone bumped into the table mid-spinup. Or the dye that is used as flow tracer has a different density for one group (less diluted? Different temperature?) and thus behaves differently. Or dye is put in a different spot in the tank and thus shows different features of the flow field. There are so many tiny things that can and will be different from experiment to experiment, and it’s a great learning experience to see an ensemble of different implementations and discuss what change in boundary conditions made results look different rather than just seeing one implementation and wrongly assuming that this is the one and only way this experiment always turns out.

Seeing many different experiments at the same time

And then, there is of course the opportunity to have different student groups work on different experiments simultaneously, which cuts down on total prep and spin-up time and enables students to see a larger variety of experiments. It also opens up the possibility that students pick what experiment they want to work on – either new ones or repeating older ones that they would like to take better pictures of or modify something in the boundary conditions. This seems to be very motivating!

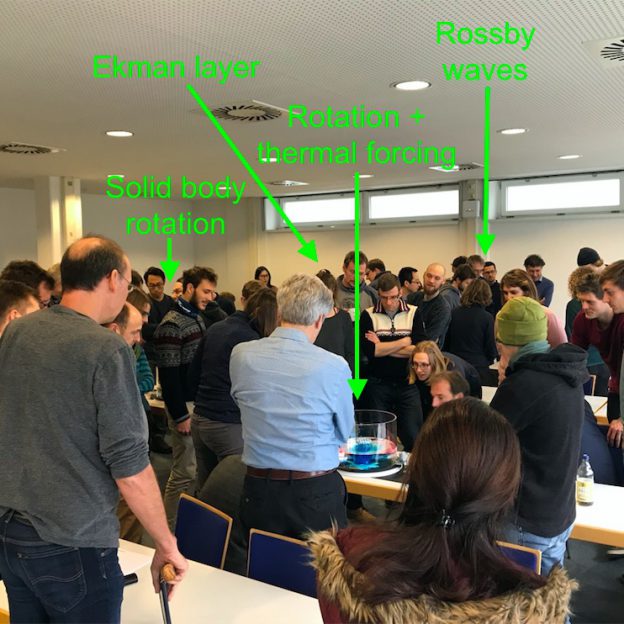

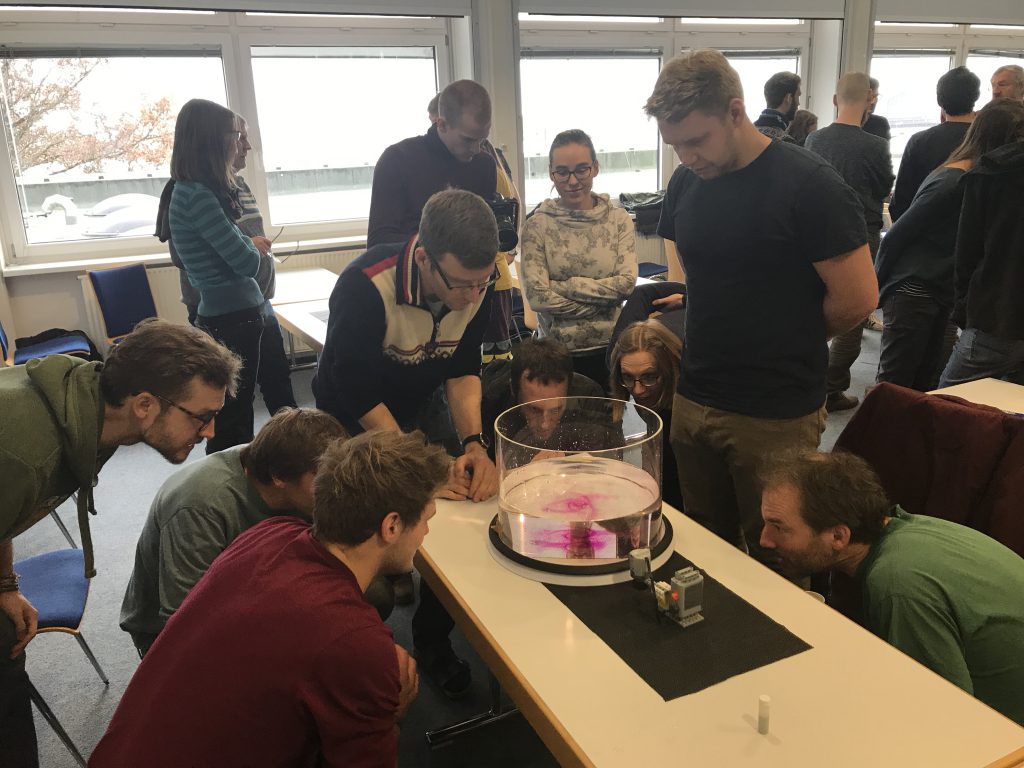

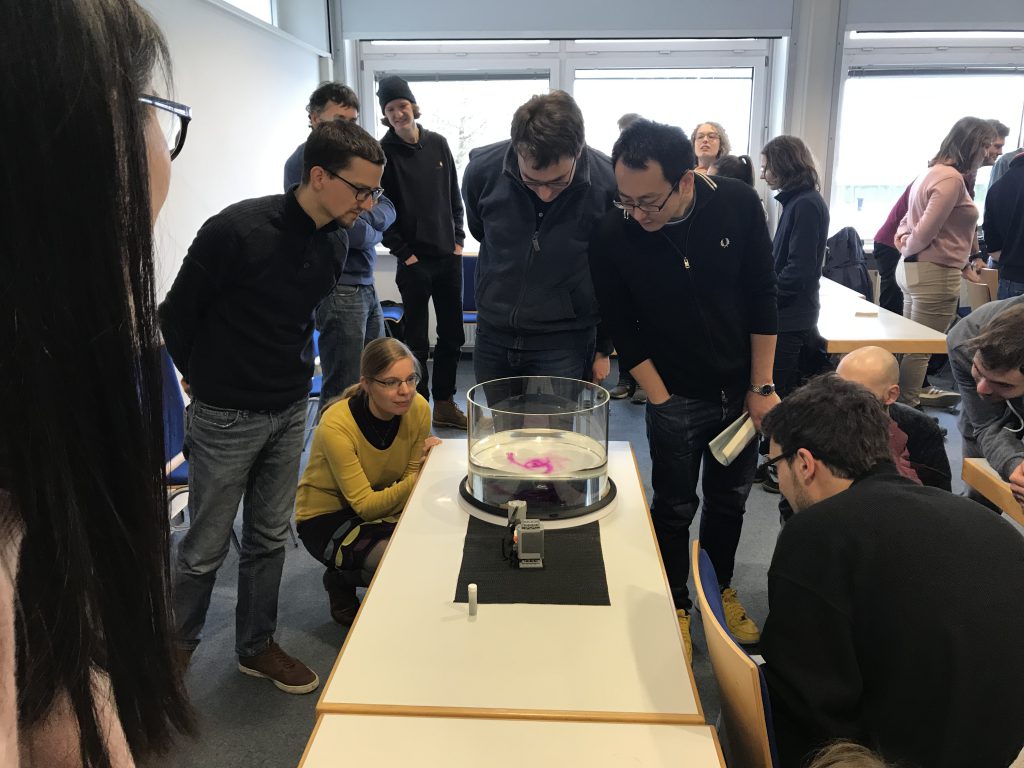

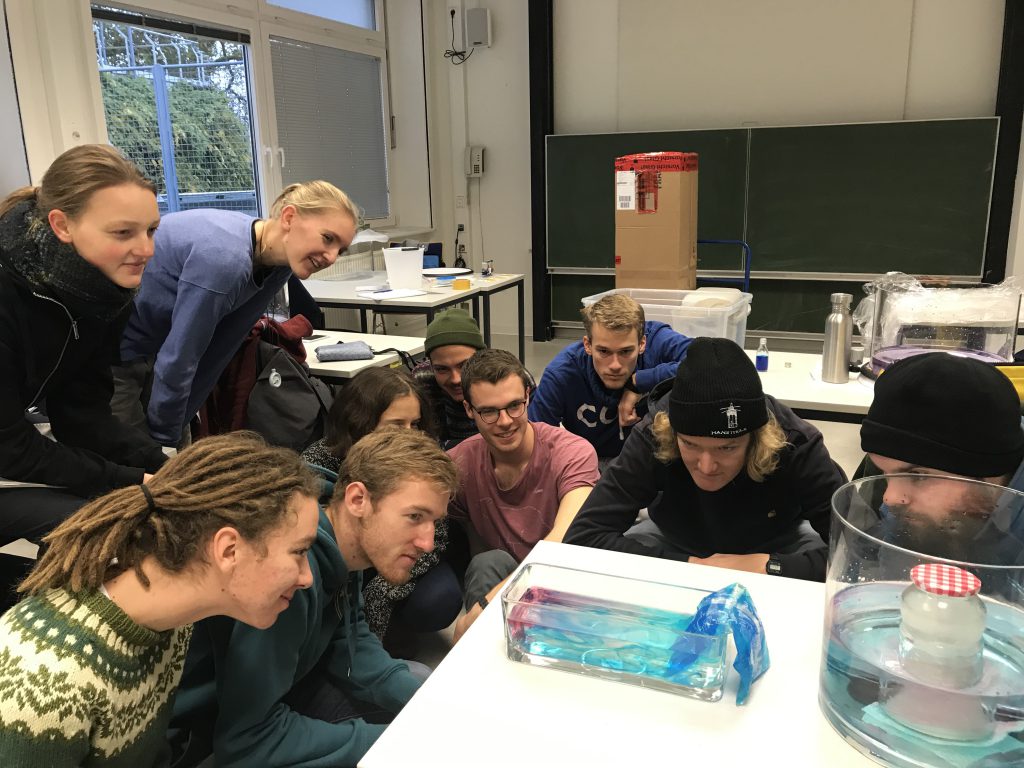

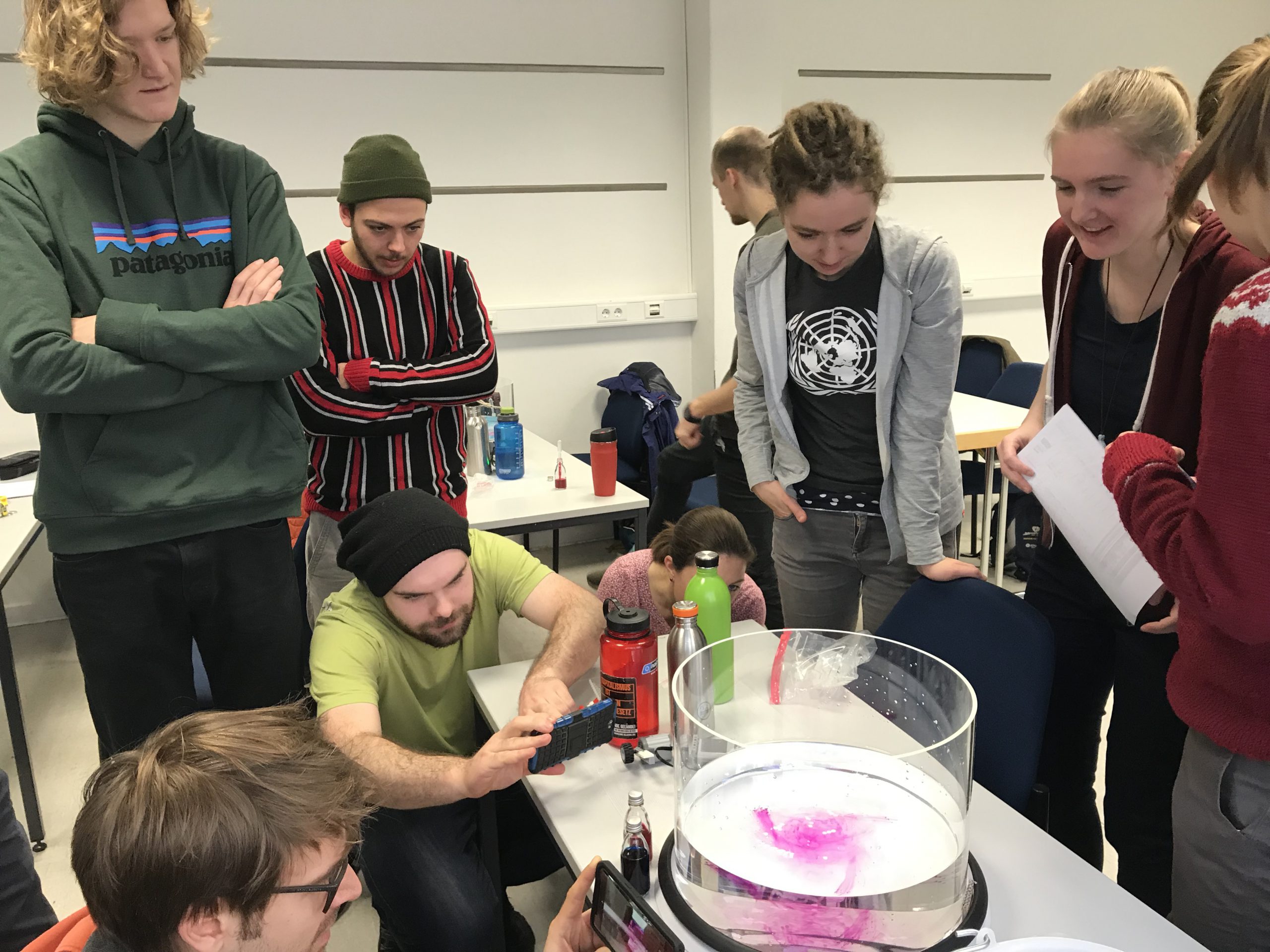

Our group of students coming together at one tank to discuss observations. Note that in the background a square tank is sitting on a different rotating table, being spun up for the Rossby wave experiment described below

Why we are using higher-walled tanks

In contrast to the tanks we’ve seen used on the DIYnamics rotating tables before, we chose to invest in some high-walled tanks.

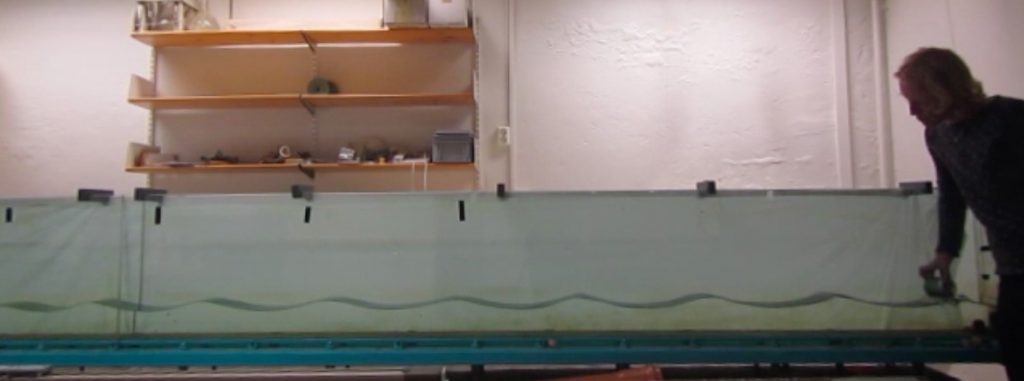

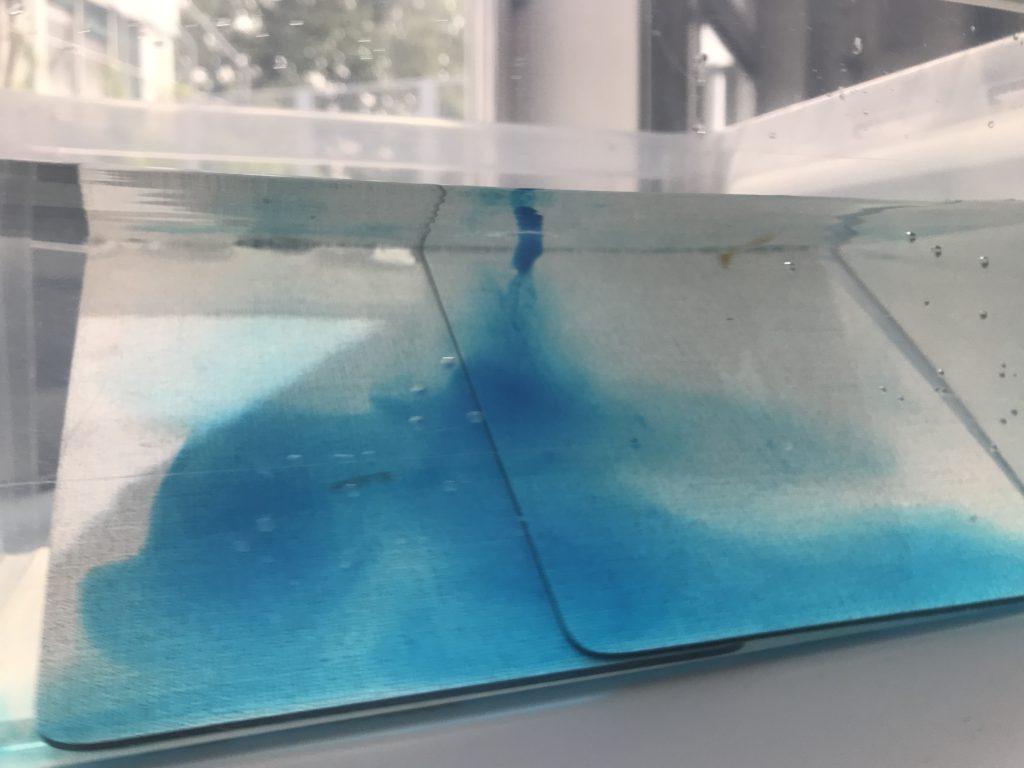

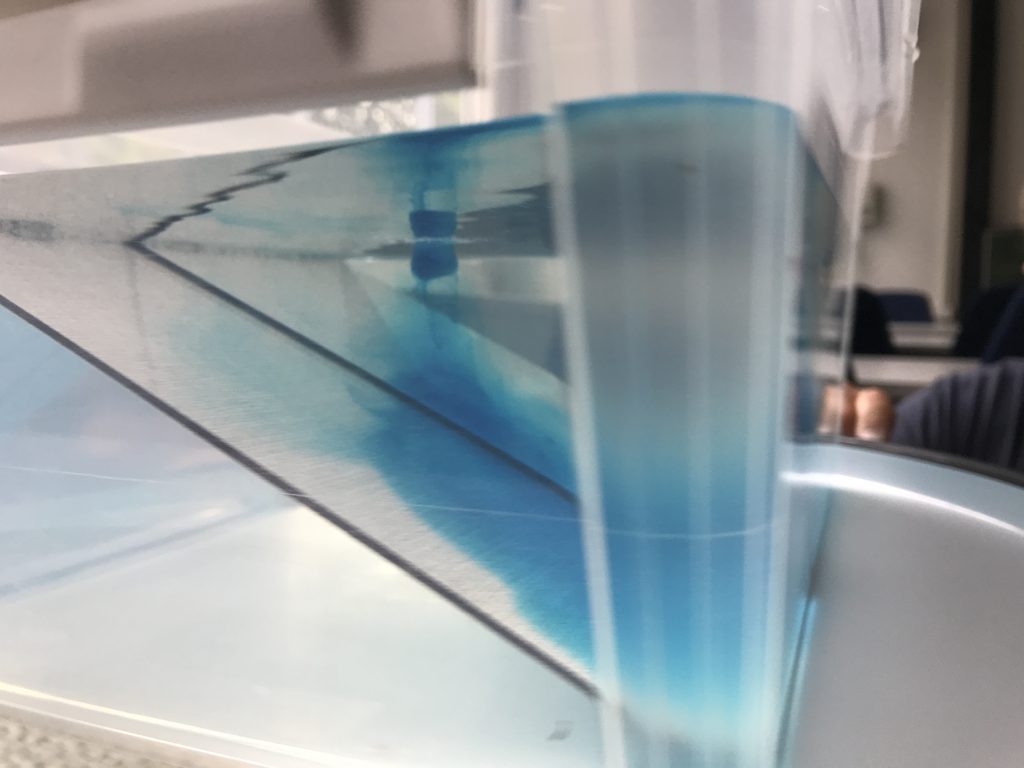

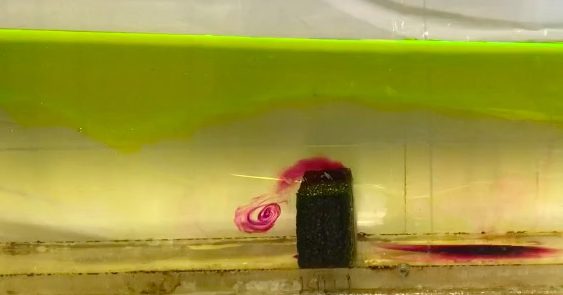

An interesting feature of rotating fluid dynamics is that the flow becomes 2D, so technically having a shallow layer of water is completely sufficient to give a good representation of those flows. And if we look at the aspect ratios of the oceans, they are in fact extremely shallow compared to their horizontal extent. But it’s easy to see a 2D flow in a shallow tank and assume that it’s 2D because of the shape of the tank, not because of the flow itself. So having an exaggerated third (depth) dimension that can be easily observed by looking into the tank from the side actually helps drive home the point that there is “nothing to see” on that dimension because the flow really is as 2D as theory told us it would be.

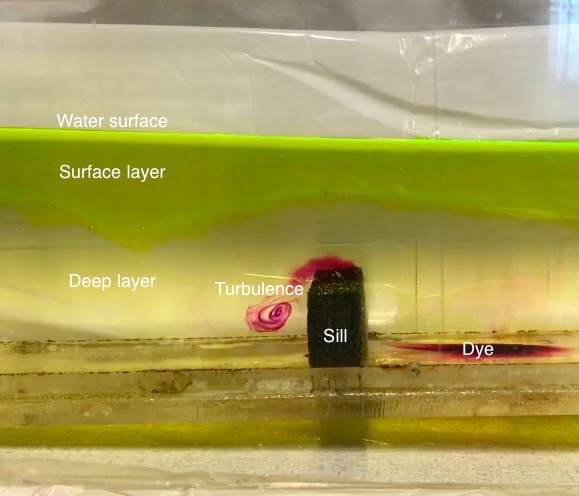

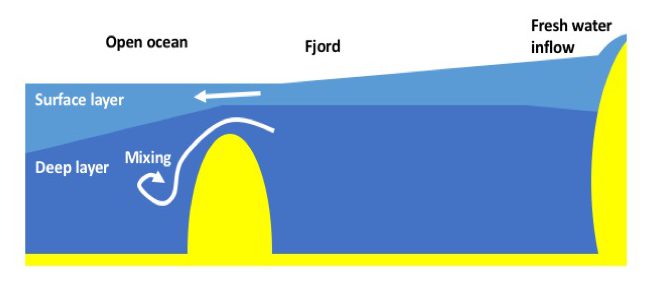

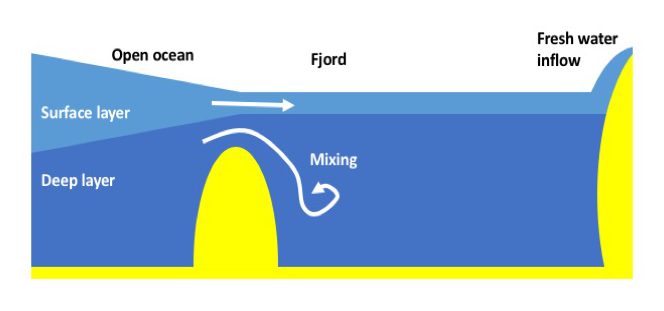

But then there are of course the cases where the flow isn’t 2D, and then a higher-walled tank is really convenient. For some experiments where there are exciting things to discover by looking into the tank from the side, check out this blog post over on my blog.

Students working with an experiment on the Ekman bottom boundary layer – one of the experiments that really benefit from a larger water depth because this allows for observations of the development of the boundary layer over time.

Experiment on planetary Rossby waves

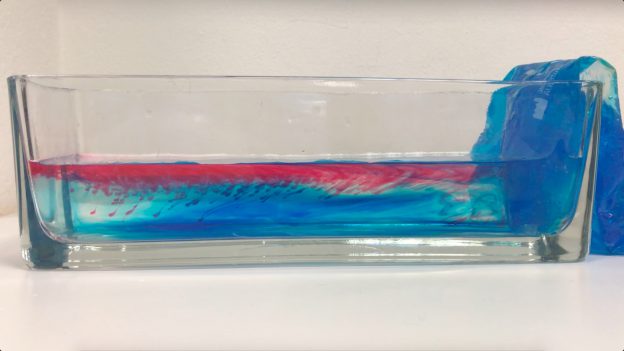

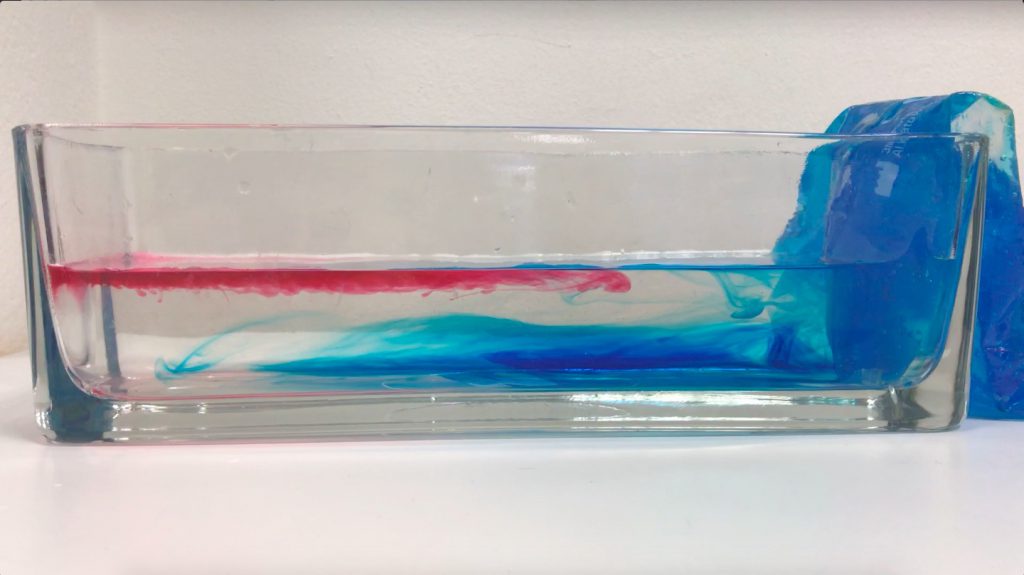

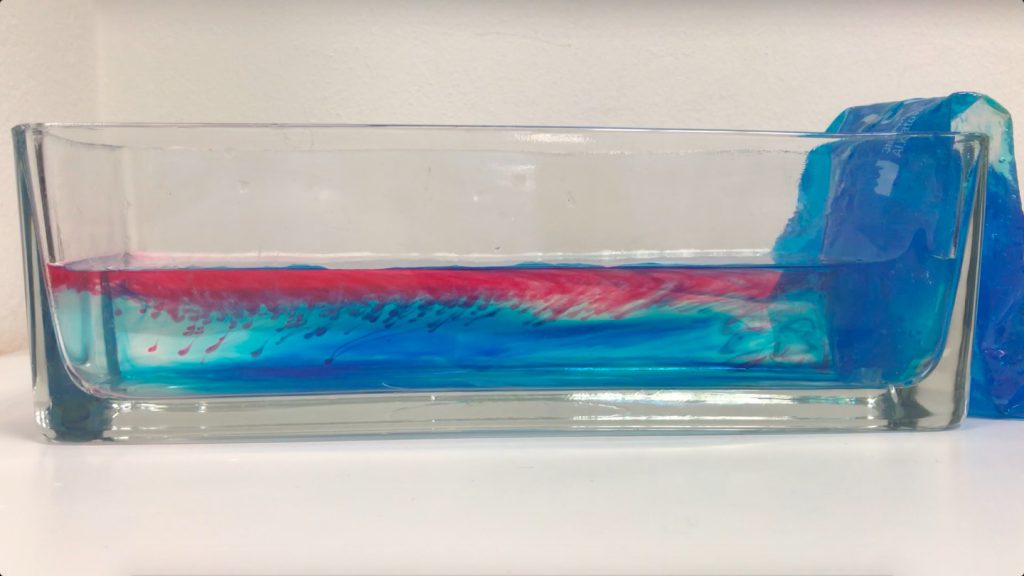

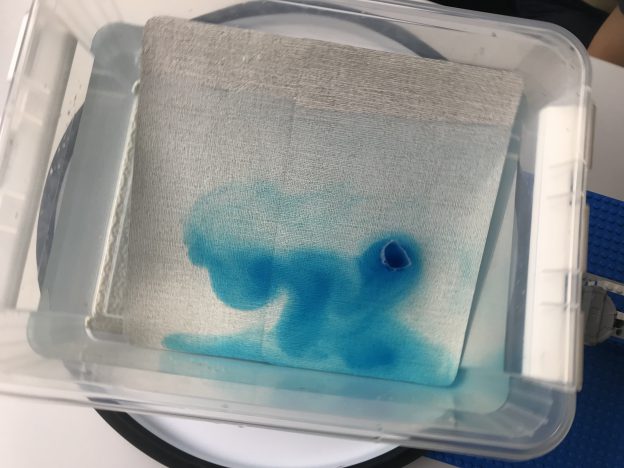

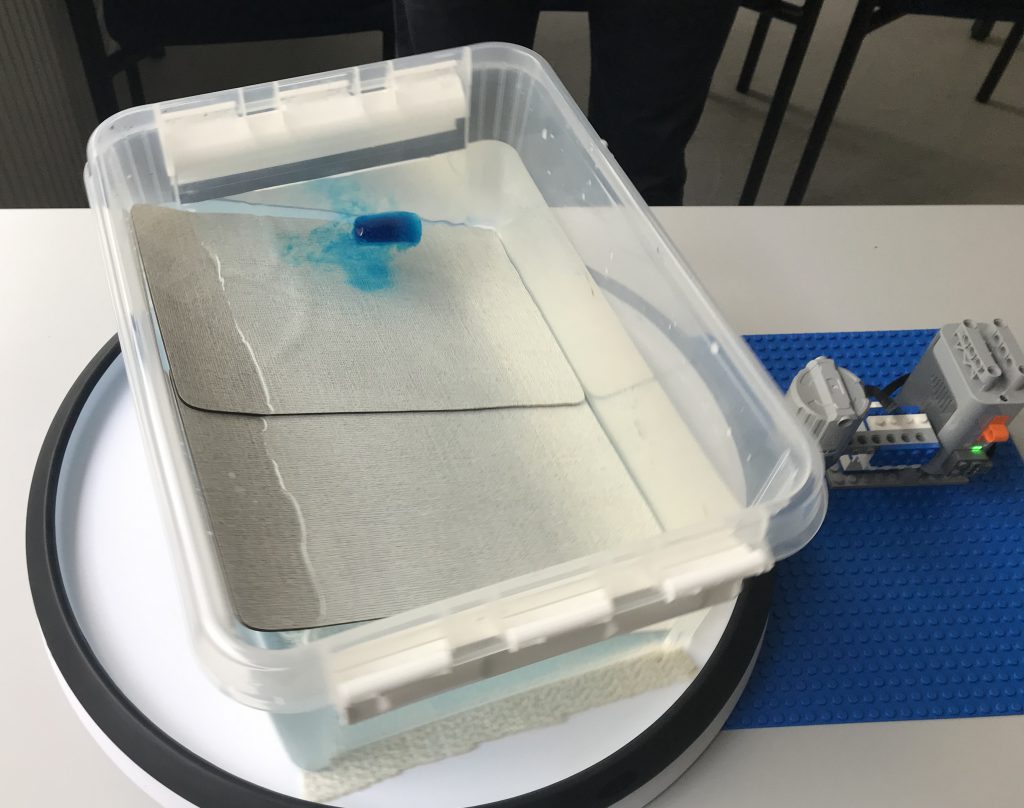

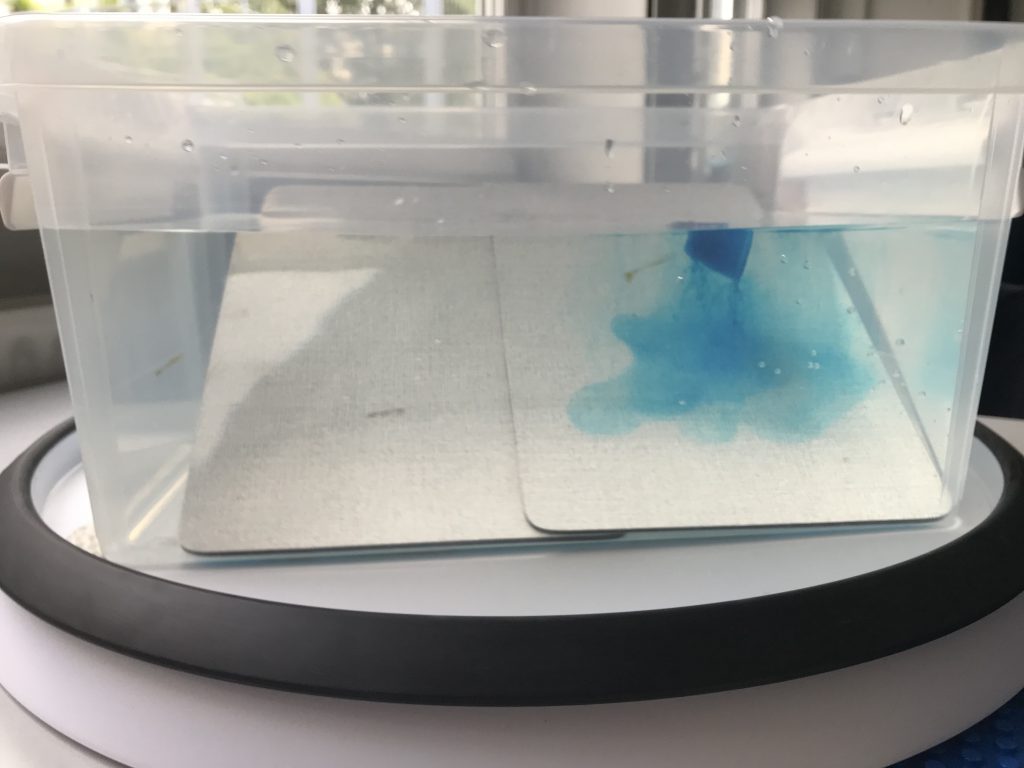

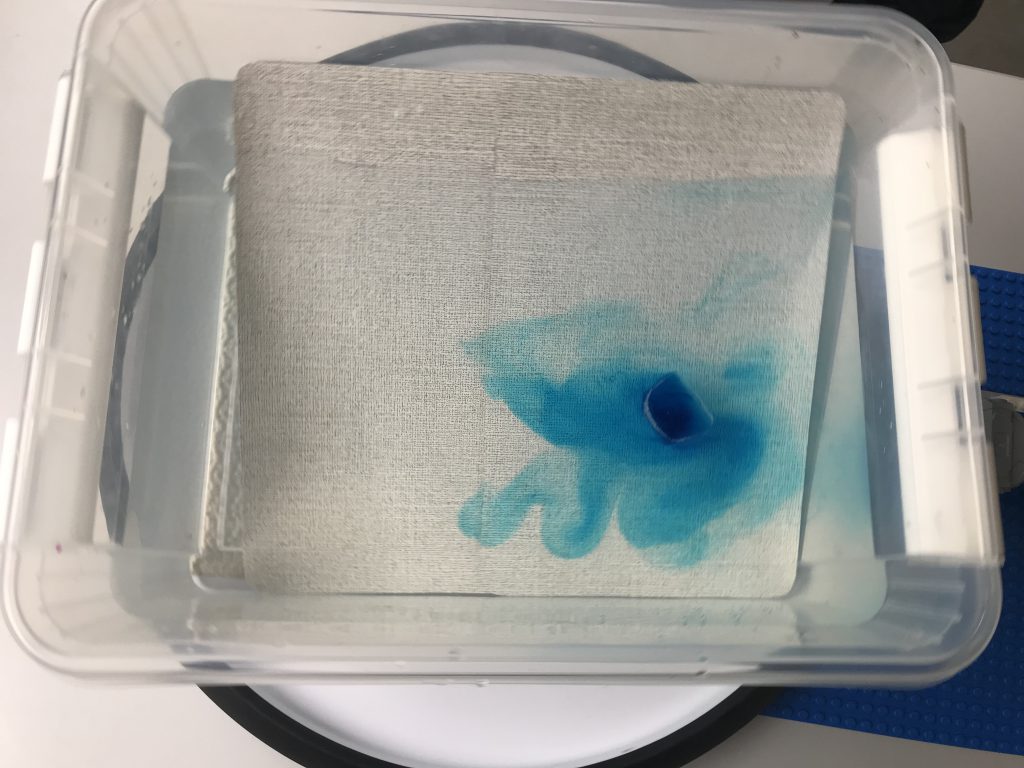

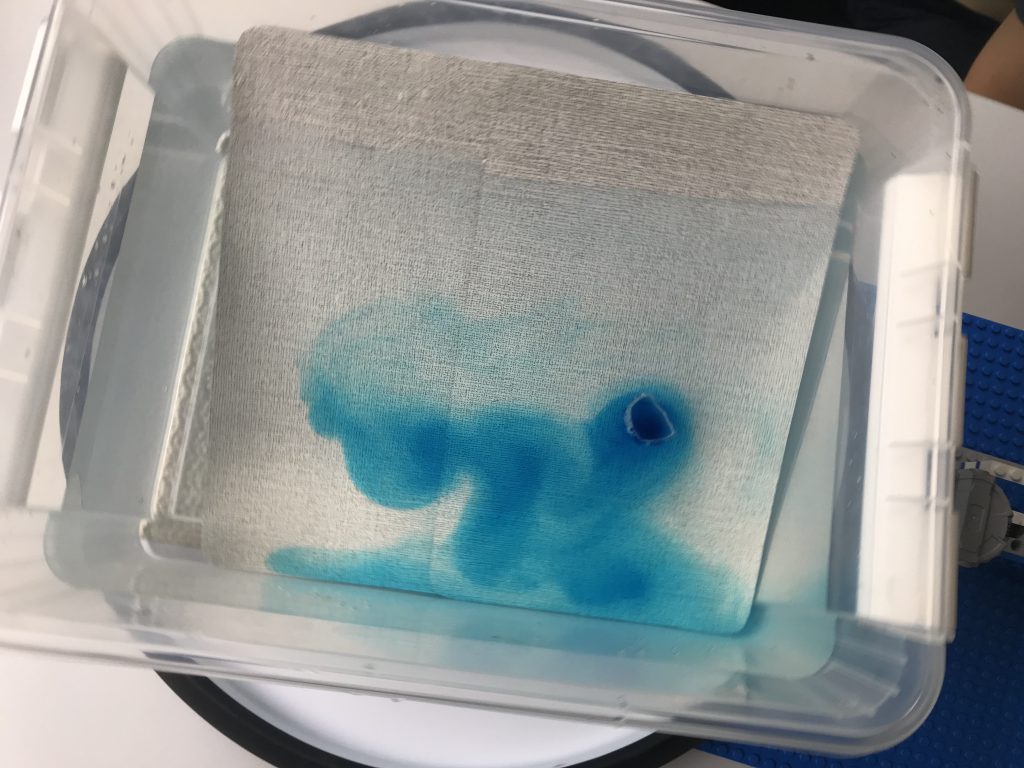

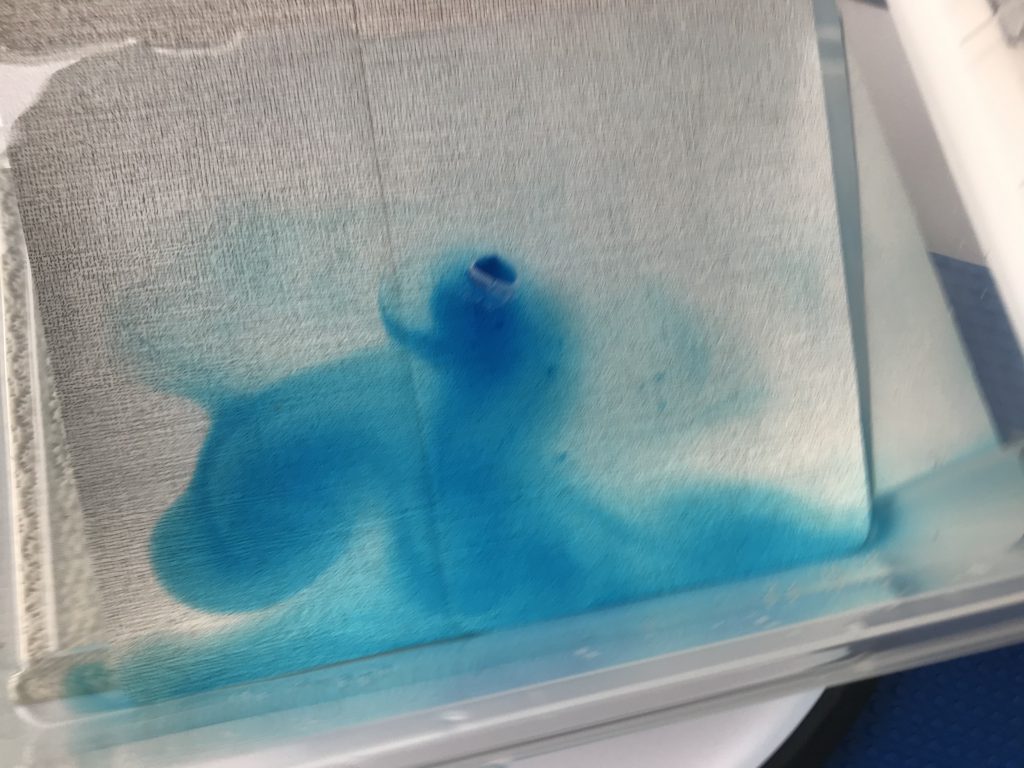

One of the first experiments we tried on our DIYnamics rotating table was a “planetary Rossby wave” experiment. We hadn’t bought our cylindrical tanks yet (read more about those below), so using a clear plastic storage box was very convenient. Btw, this is one of the experiments where looking into the tank from the side gives a lot of interesting insights!

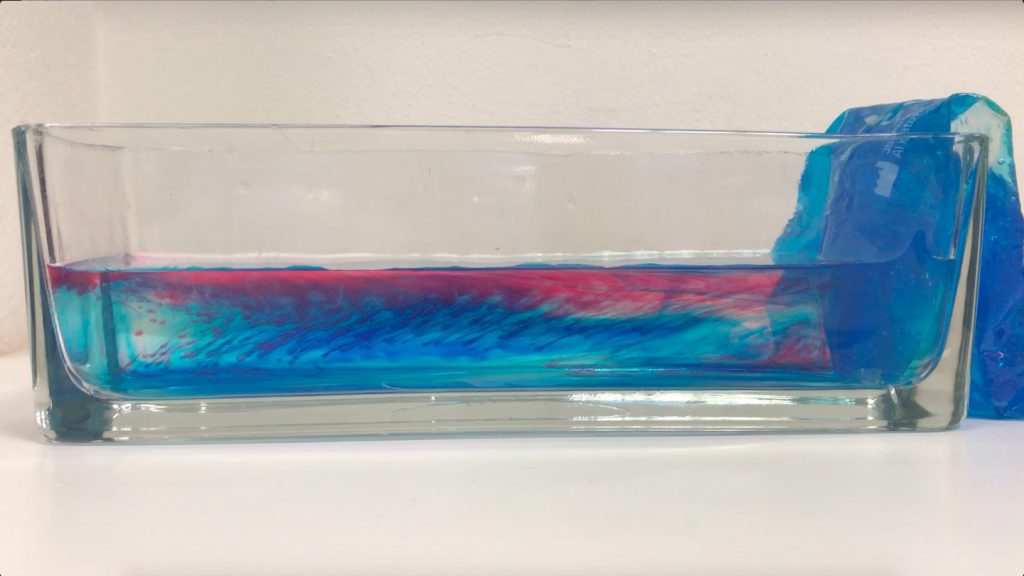

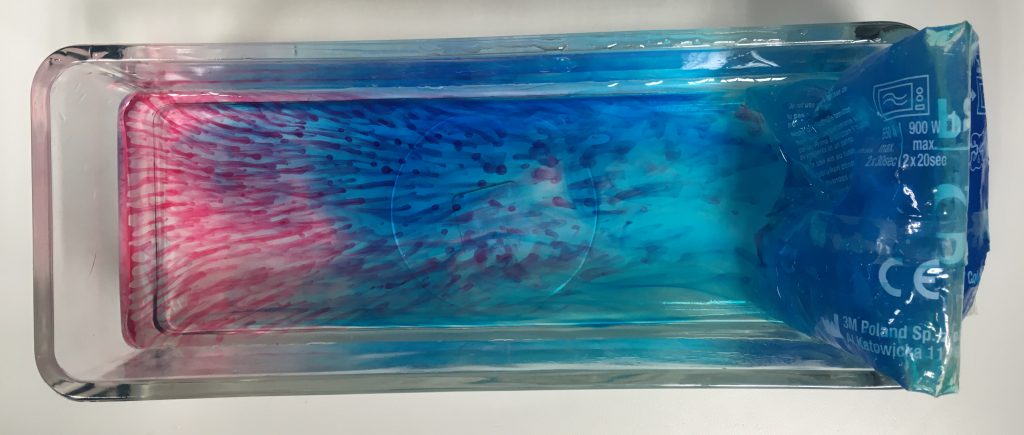

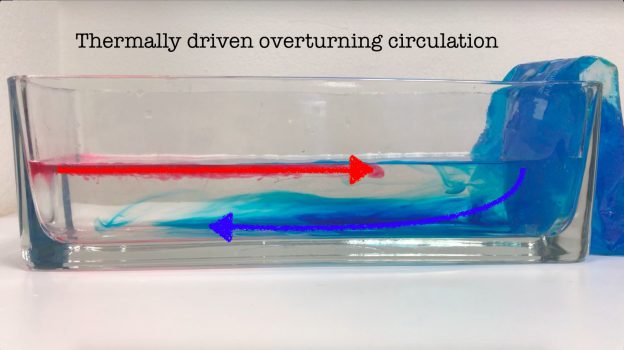

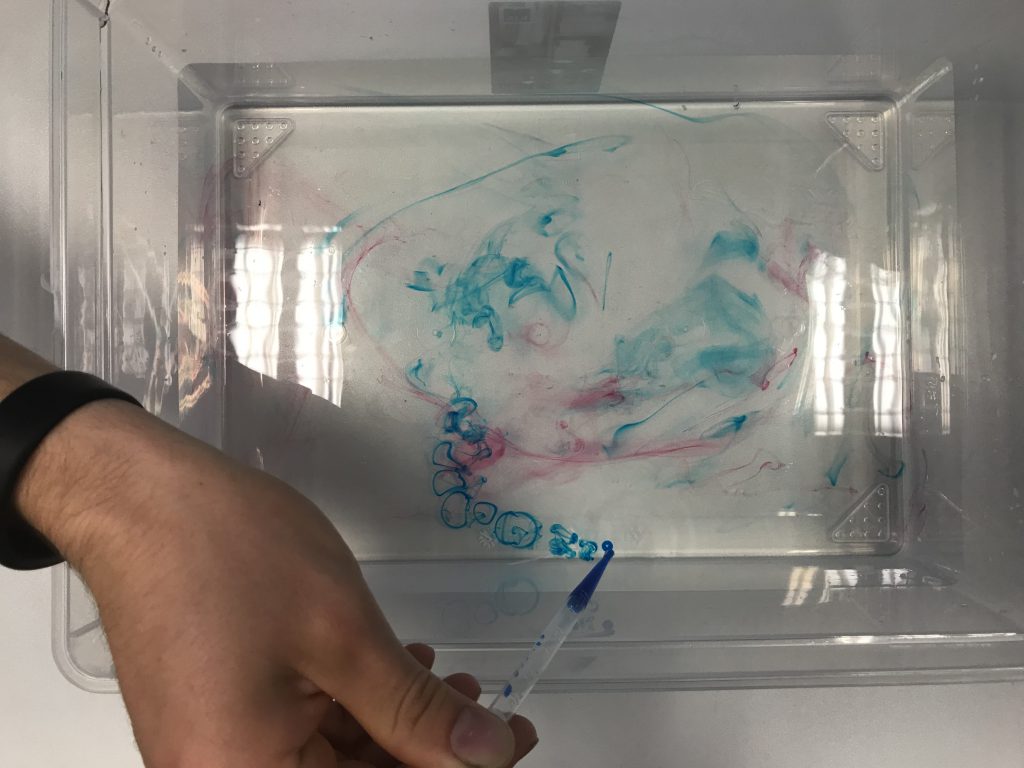

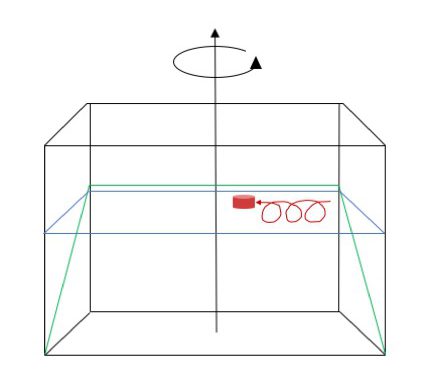

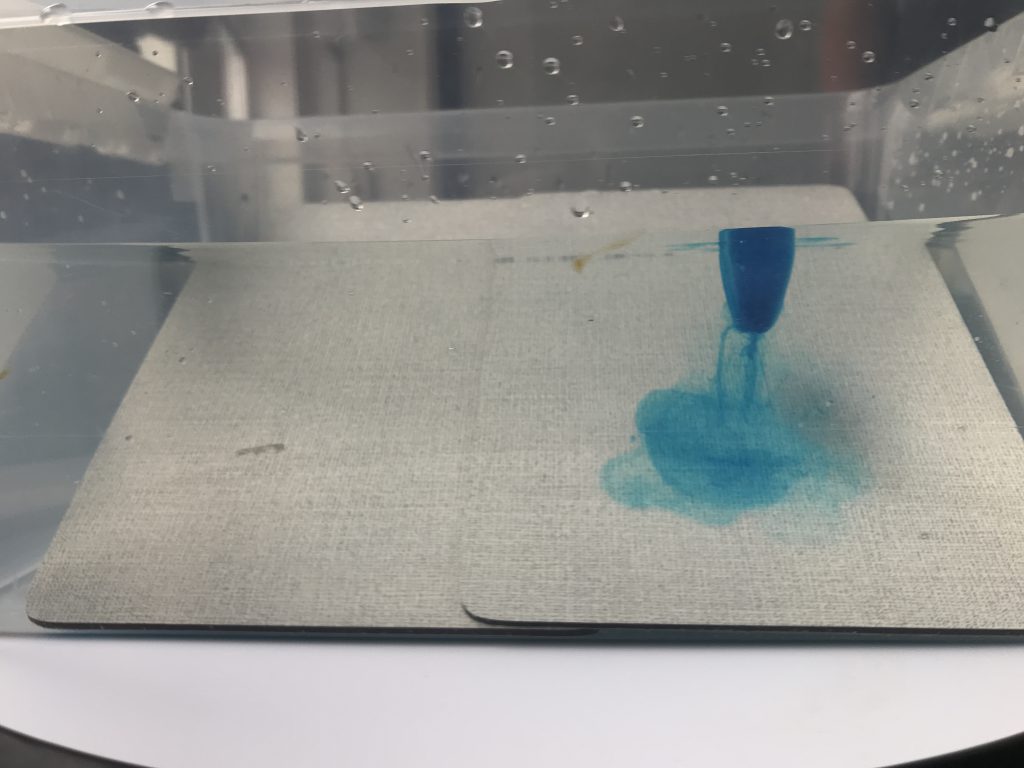

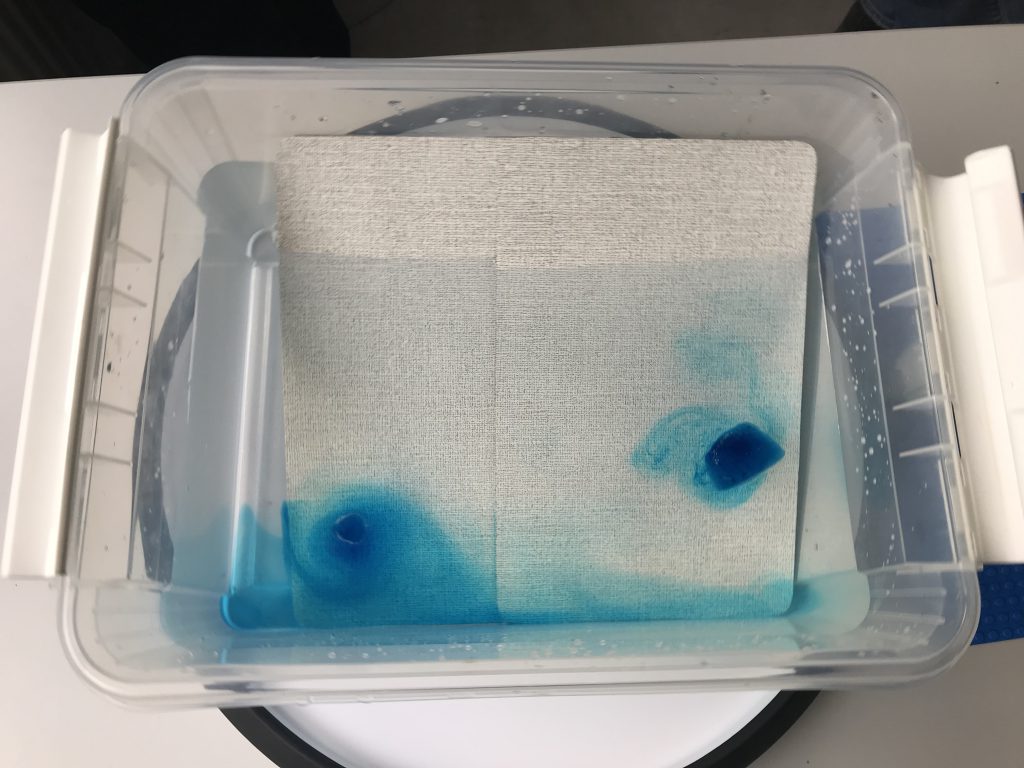

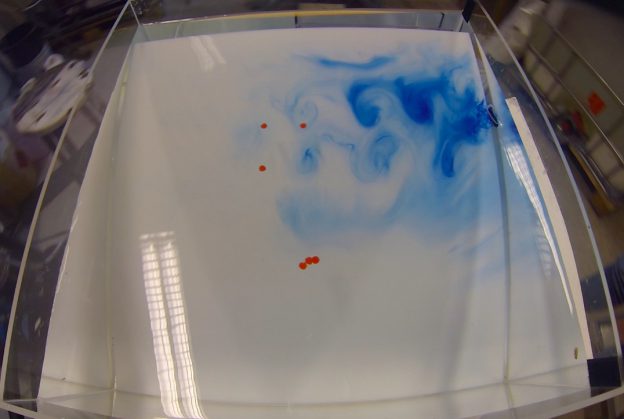

For the planetary Rossby wave experiment, we need a sloping bottom (easiest done in a rectangular tank, but we’ve also run the same experiment on a cone-shaped insert in a cylindrical tank) and a dyed ice cube. When the tank is in solid body rotation, a dyed ice cube is inserted in the shallow “eastern” corner of the tank (make sure it is sitting far enough from the edge of the tank so it can turn around its own axis unobstructed). For more details see this blog post, but in a nutshell: The cold melt water sinks, setting up a column of spinning water that sheds spinning eddies at regular intervals. Eddies and ice cube propagate westwards. This is a really easy and fool-proof experiment, and it looks beautiful!

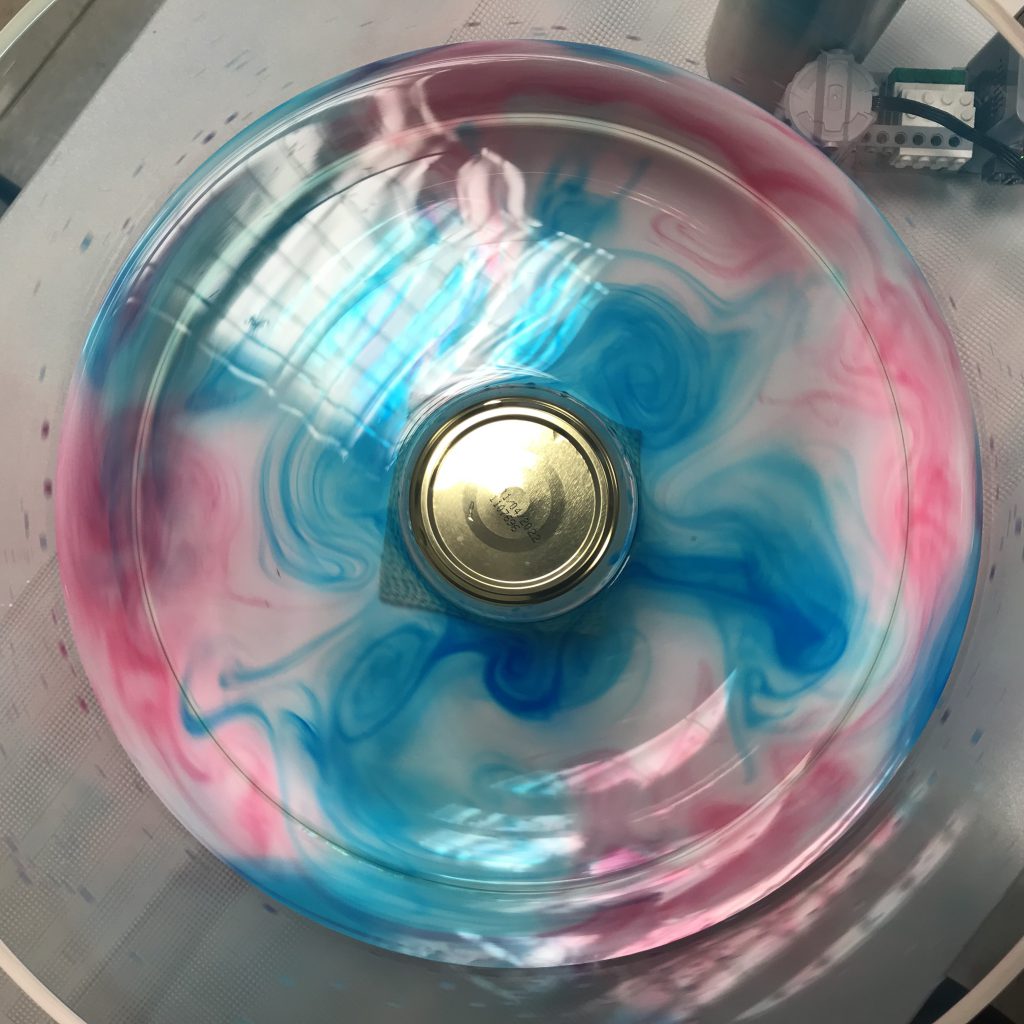

Planetary Rossby waves in a square tank with a sloping bottom.

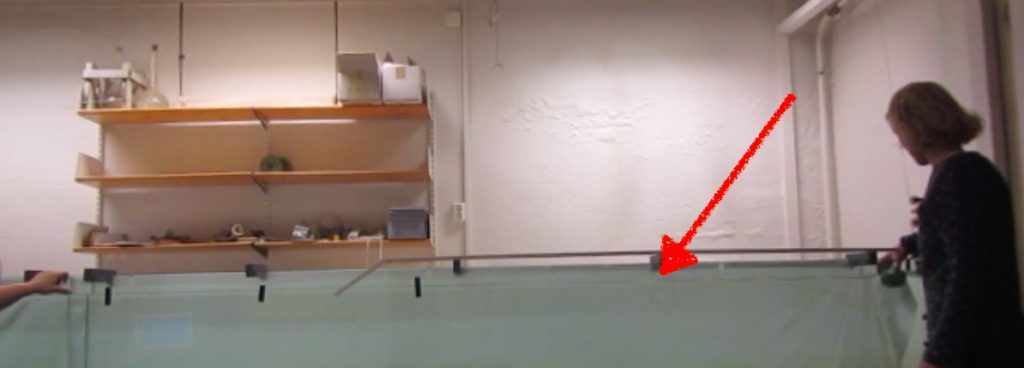

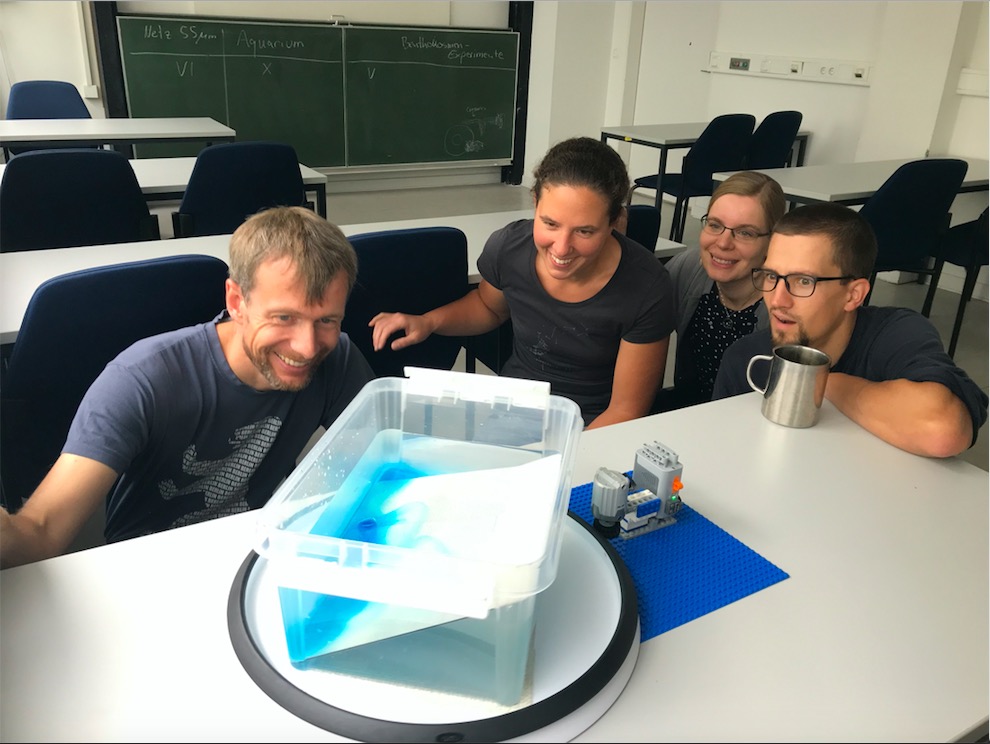

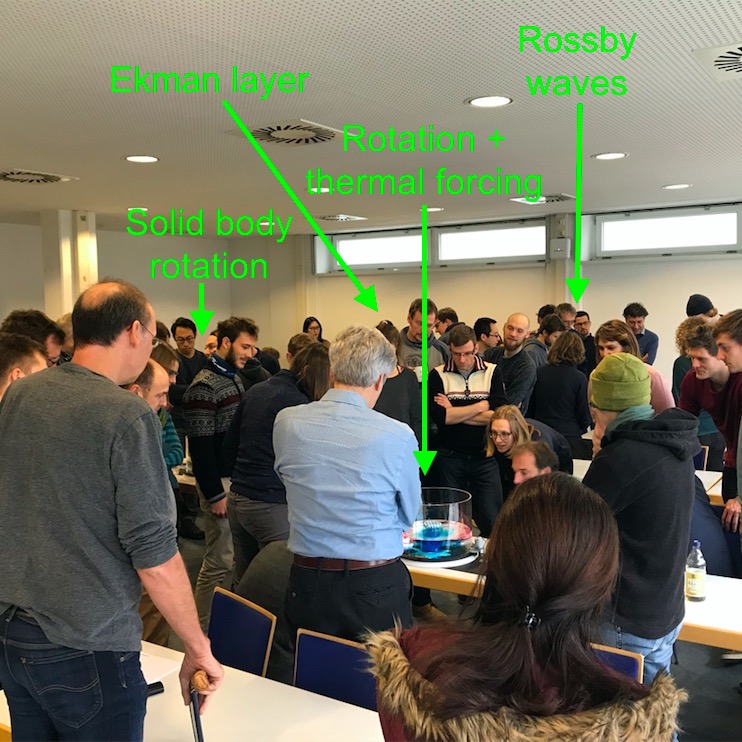

Presenting the DIYnamics tanks at an institute colloquium

In January, Torge and I gave a seminar presentation titled “you should really play more often! Using tank experiments in teaching” at our institute’s colloquium. In the abstract, we announced that we would give a brief overview over our project and then give people the opportunity to play – which we did. We had been expecting that maybe a handful of our loyal friends would stick around after the presentation to look at the tanks, but we were very surprised and excited to see that pretty much everybody in the audience wanted to stay. We had set up the four rotating tables with four different experiments and a student presenting at each in the back of the room, and we ended up running all the experiments repeatedly, until we were kicked out of the room because the next lecture was about to start. It was really motivating to see how everyone – students, PhD students, postdocs, staff, professors – got really excited and wanted to learn more about the tank experiments, discuss observations, modify and experiment. This goes to show that an affordable rotating table is an amazing tool at every level of education: There is always more to discover!

A snapshot of the audience of our seminar presentation interacting with the tanks and each other. We were running four experiments simultaneously.

Follow our experiences

If you want to follow our experiences with the DIYnamics rotating tables, there are several options for you:

Torge and I have recently launched the “Teaching Ocean Science” blog at https://www.oceanblogs.org/teachingoceanscience/, which is a joint effort of ourselves and other instructors, describing fun hands-on stuff they do in their teaching, and students, who write course assignments on what they are currently learning for the blog.

Additionally, all the outgoing links in my guest post above are to posts on my own blog, “Adventures in Teaching and Oceanography”, at https://mirjamglessmer.com/blog. I use that blog as my own archive and document every new thing I try on there, so you might want to sign up for email alerts or follow via my Twitter @meermini.

In addition to writing about the DIYnamics rotating tables and what we are up to with those (and you can be sure that if I played with a tank, you will read it on that blog right away ;-)), I write a lot about#KitchenOceanography (which are very easy hands-on experiments on ocean and climate topics that you can do with household items) and #WaveWatching (observing ocean physics everywhere, all the time). I also write about science communication issues.

Please feel free to check out those blogs and as I wrote in the beginning: Please get in touch if you have any comments or suggestions for us. I am always happy to chat!

(1) This project has been funded by the PerLe fund for innovative teaching through resources from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, grant number: 01LP17068. The responsibility for the content of this publication lies with the authors.