Ekman spirals — current profiles that rotate their direction over depth, caused by friction and Coriolis force — are really neat to observe in a rotating tank. I just found out that they are apparently (according to Wikipedia) called “corkscrew currents” in German, and that’s what they look like, too. I tend to think of Ekman spirals more as an interesting by-product that we observe when stopping the tank after a successful experiment, but they totally deserve to be featured in their own experiments*.

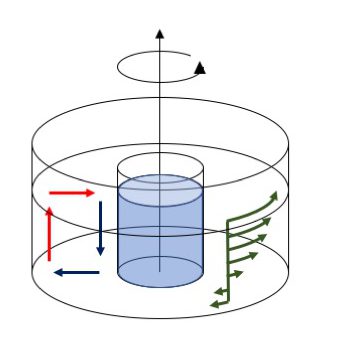

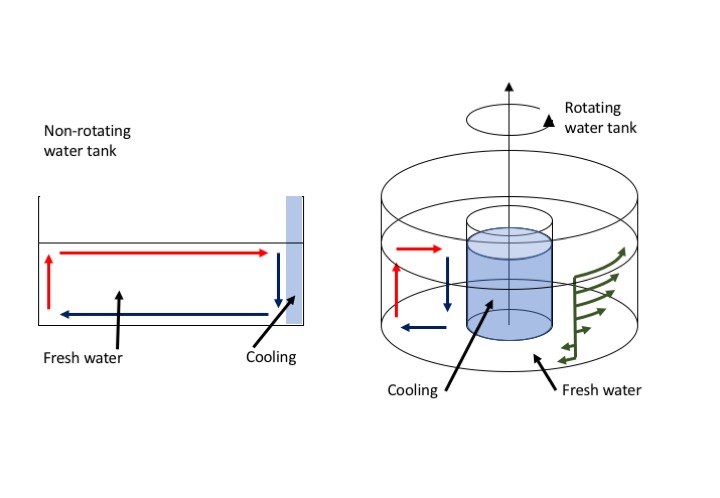

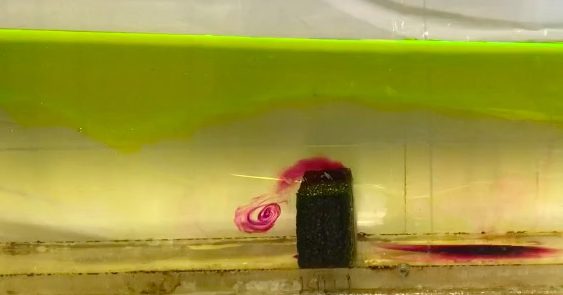

Ekman layers form whenever fluid is moving relative to a boundary in a rotating system. In a rotating tank, that is easiest achieved by moving the boundary relative to the water, i.e. by increasing or decreasing the rotation rate of a tank and observing what happens before the water has adjusted to the new rotation and has reached solid body rotation. Spinning the tank up or down creates high and low pressure systems, respectively, similar to atmospheric weather system.

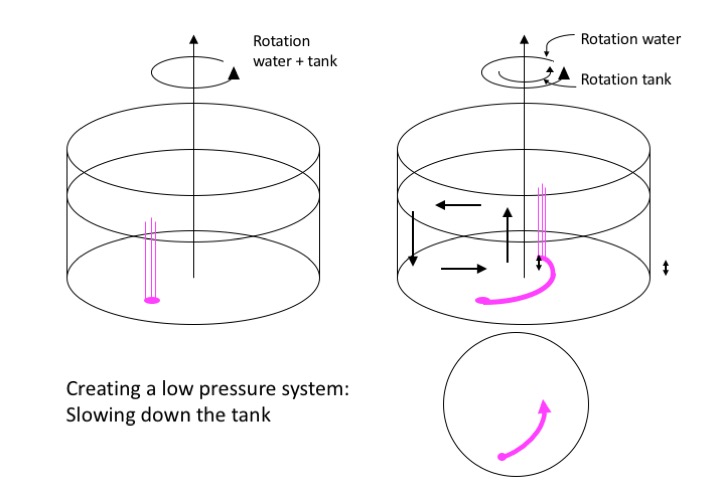

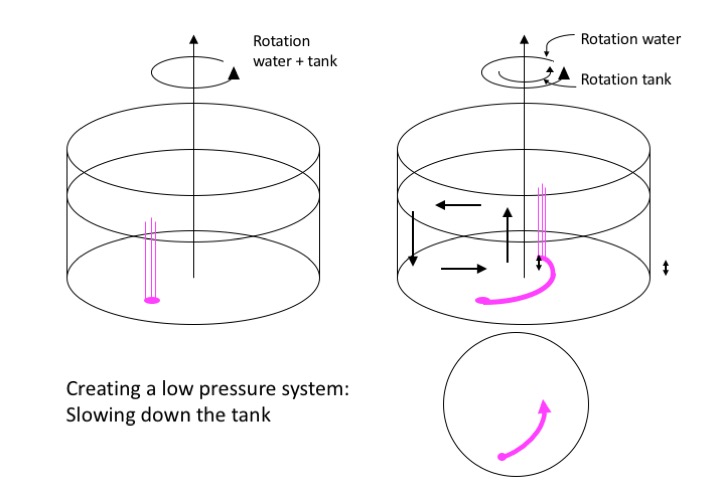

Creating a low-pressure system: Slowing down the tank

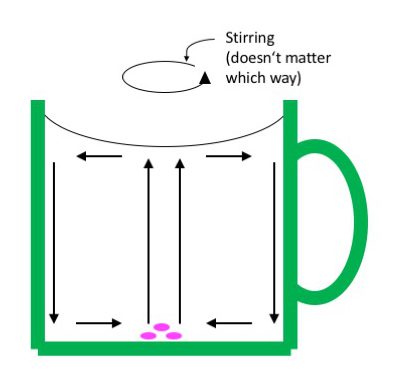

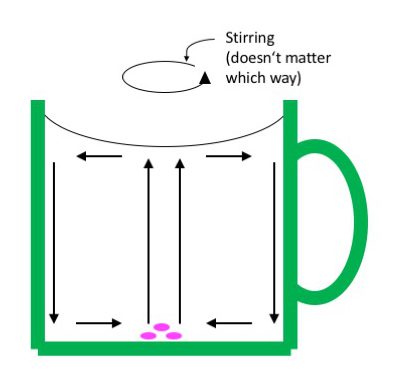

In atmospheric low pressure systems, air moves towards the center of the low pressure system, where it rises, creating the low pressure right there. This situation can probably easiest be modelled by stirring a cup of tea that has some tea leaves still in it. As the surface deforms and water bunches up at the sides, an overturning circulation is set into motion. Water sinks along the side walls and flows towards the center of the cup near the bottom. From there it rises, but any tea leaves or other stuff floating around get stuck in the middle on the bottom because they are too heavy to rise with the current. So there you have your low pressure system!

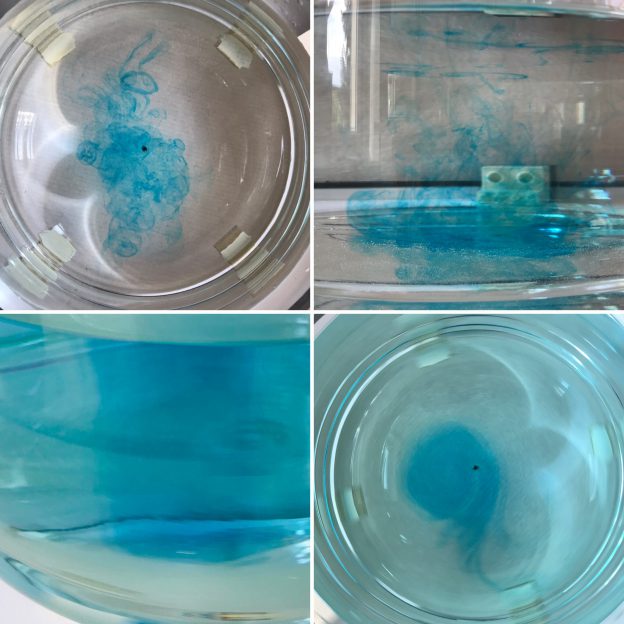

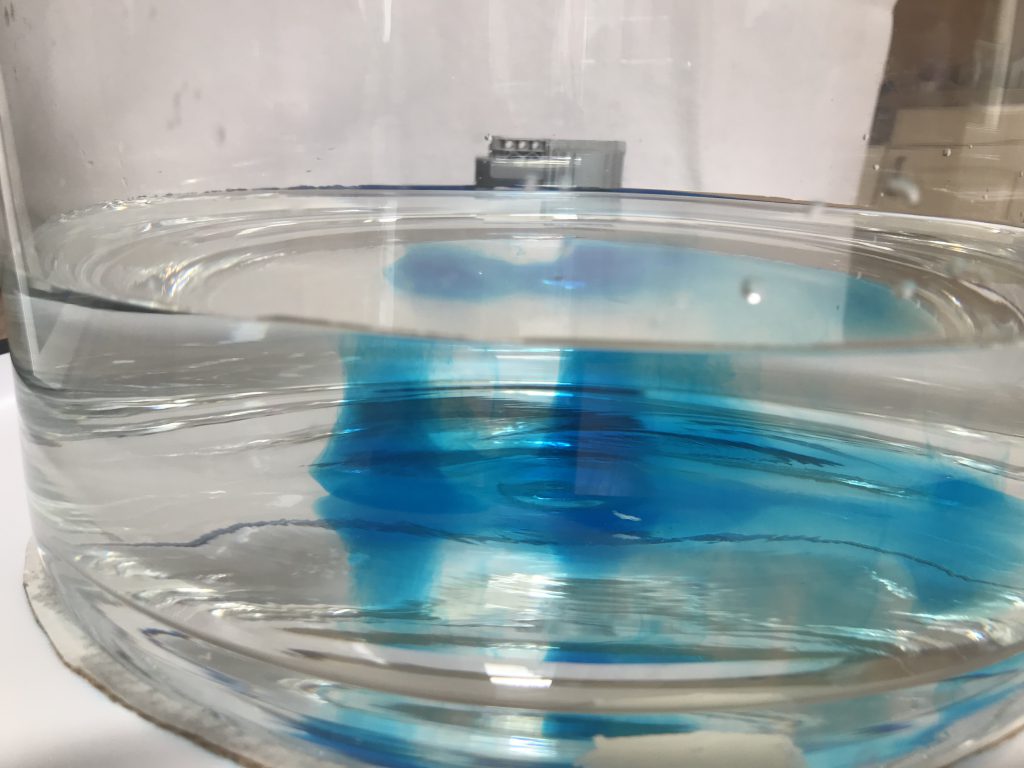

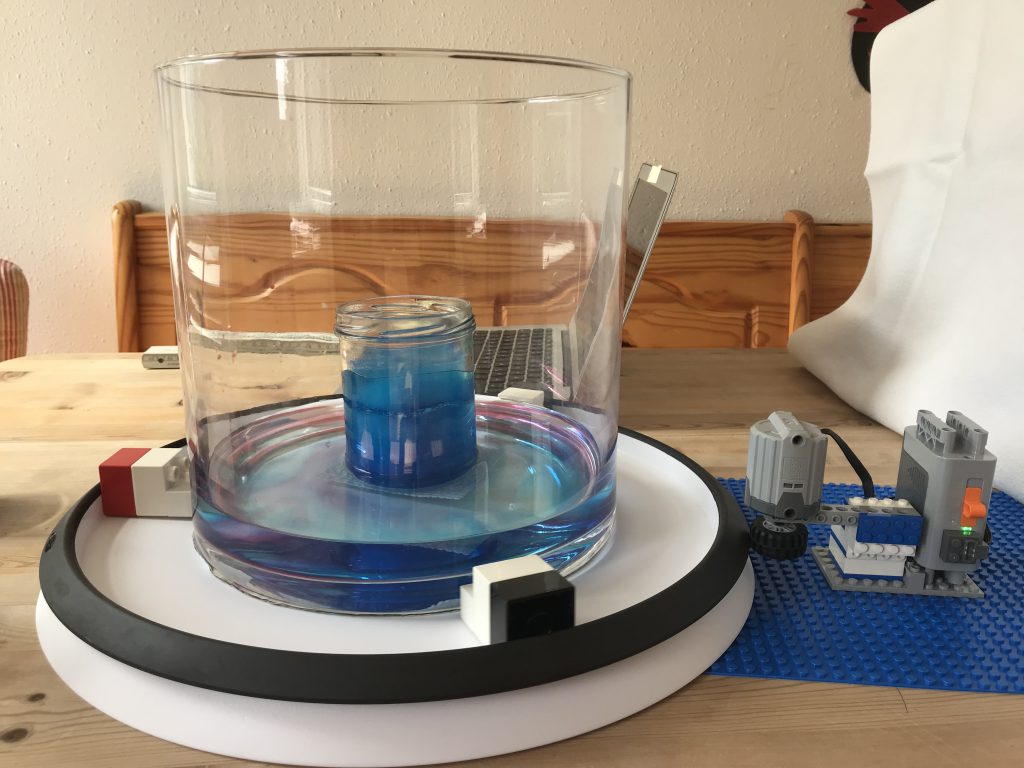

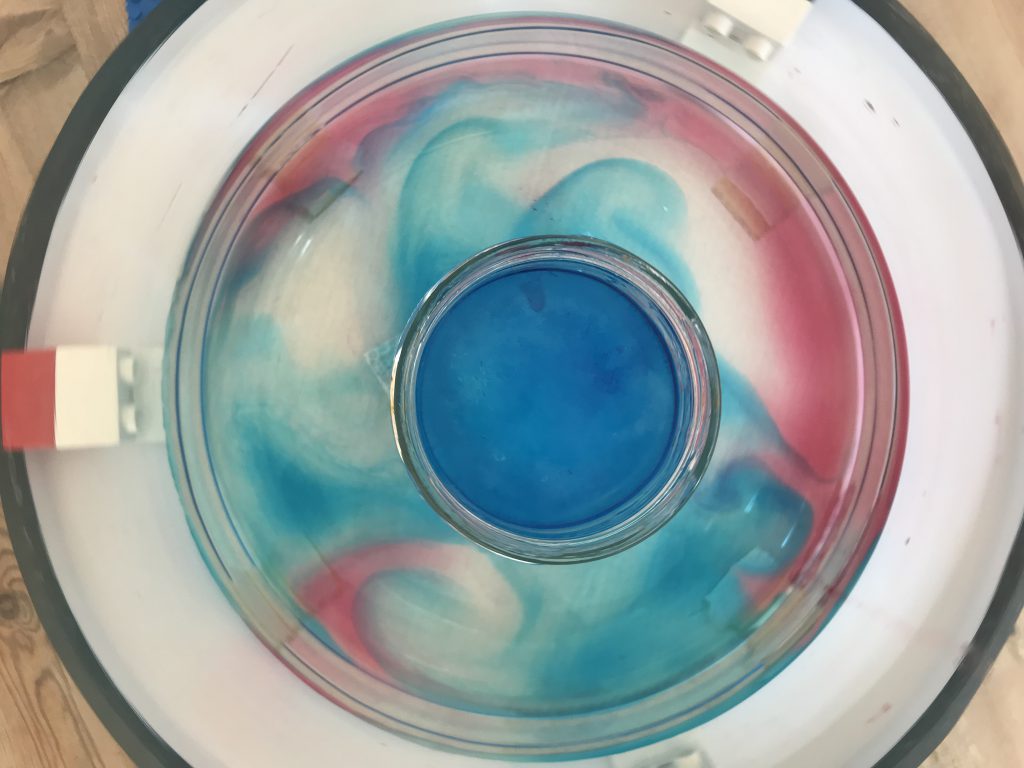

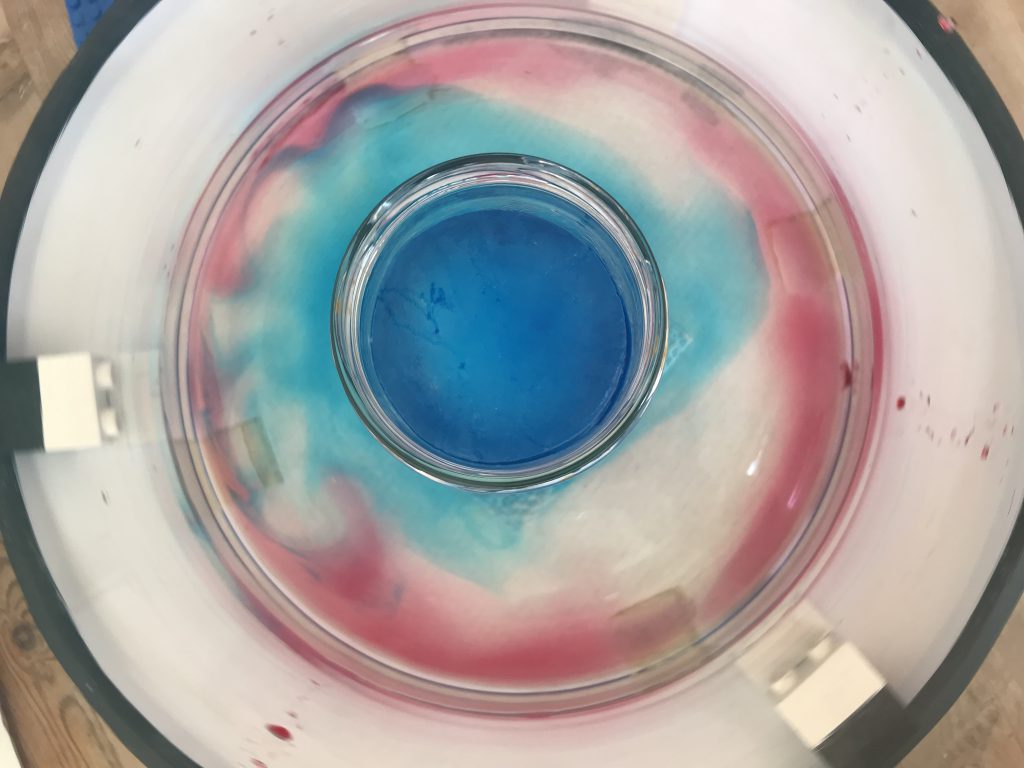

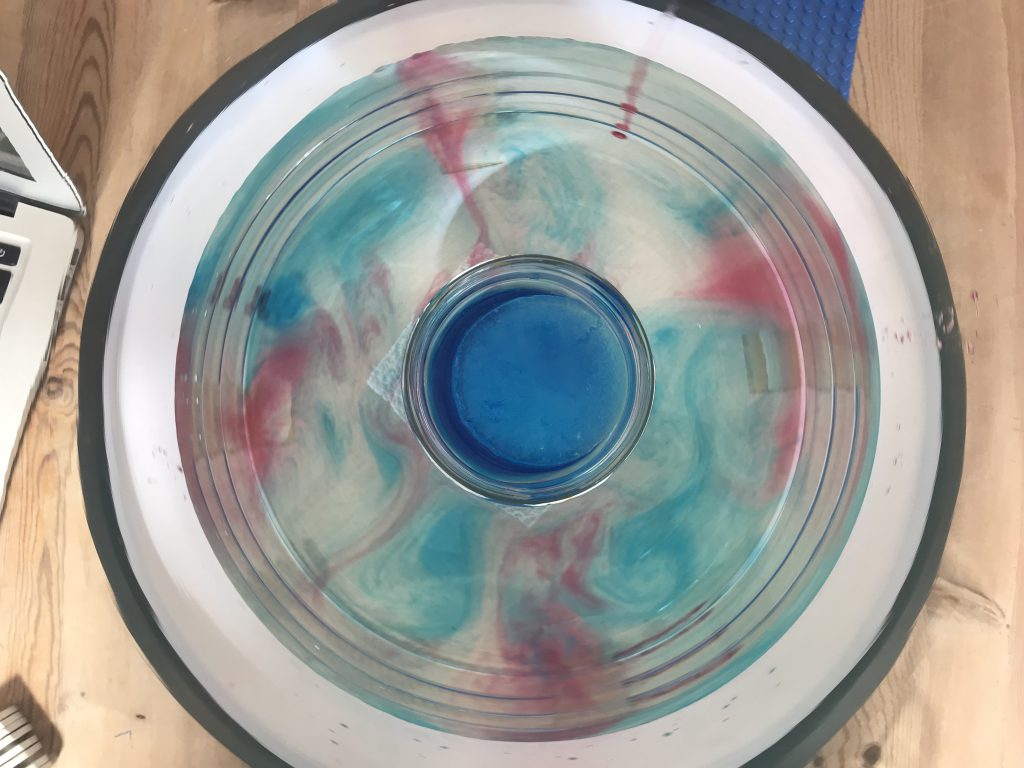

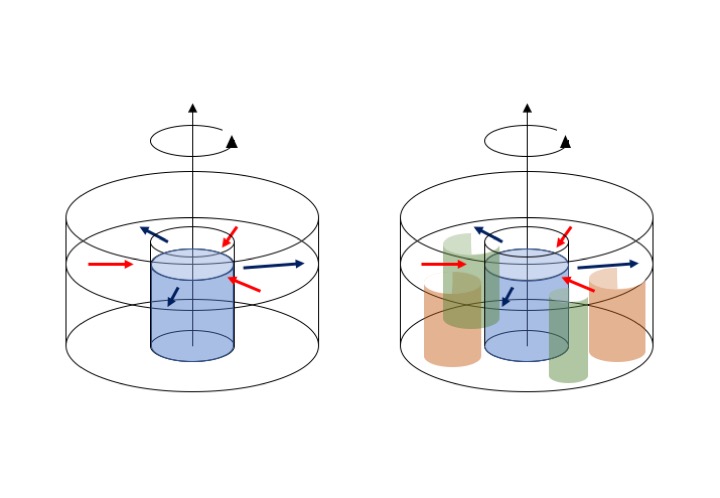

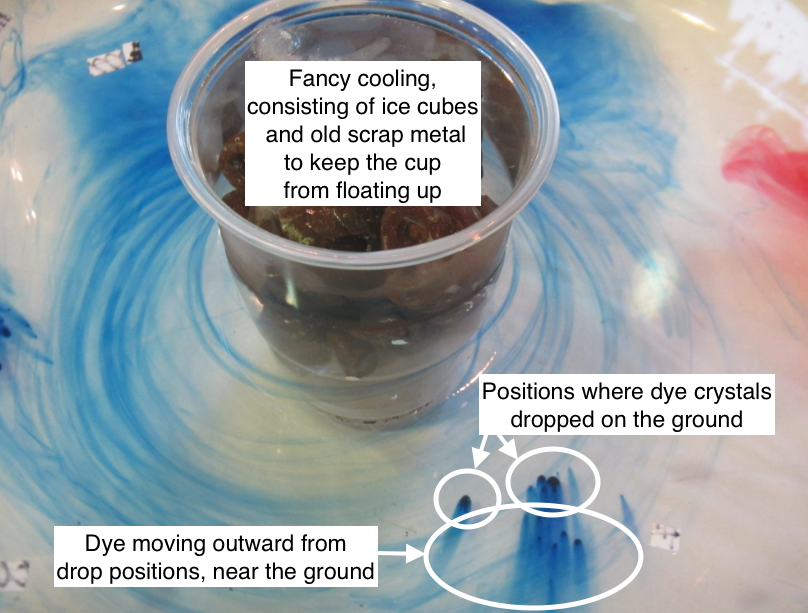

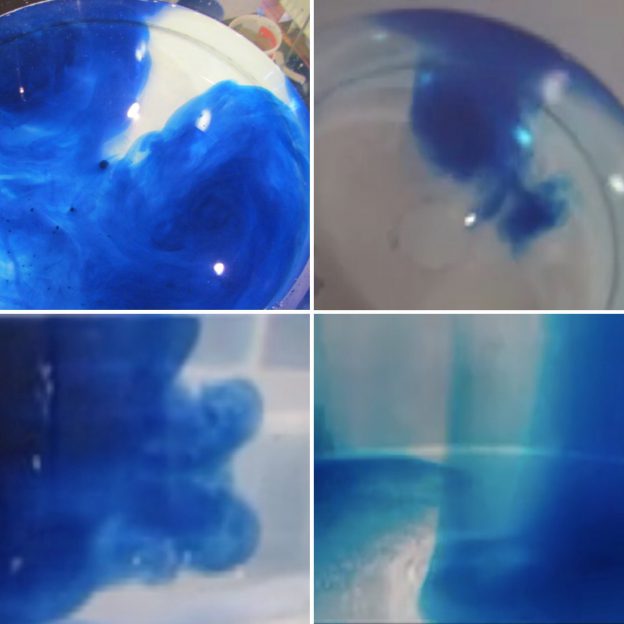

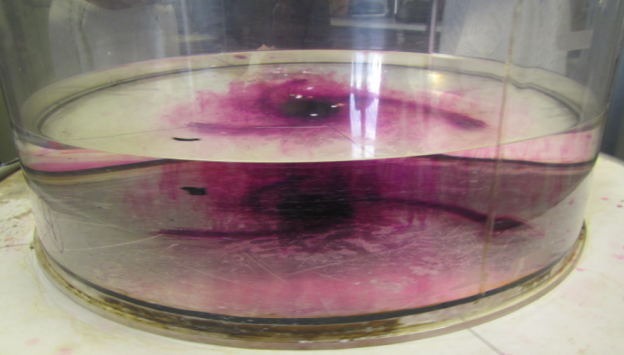

You can observe the same thing with a rotating tank, except now we don’t stir. The tank is filled with water and spun up to solid body rotation on the rotating table. When the water is in solid body rotation, a few dye crystals are dropped in, leaving vertical streaks as they are sinking to the ground (left plot in the image below).

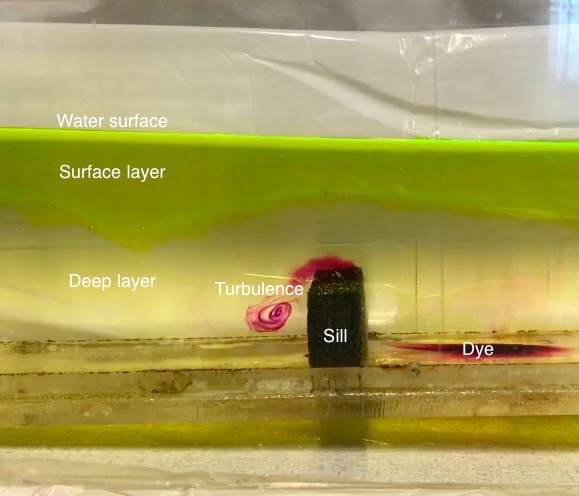

Then the tank is slowed down. The resulting friction between the water body and the tank creates a bottom Ekman spiral. The streaks of dye that were left when the dye crystals were dropped into the tank move with the water when the tank is slowed down. In the upper part of the tank, the dye stripes stay vertical. But at the bottom, within the Ekman layer, they get deformed as the bottom layer lifts up, and thus show us the depth over which the water column is influenced by bottom friction (see black double arrow in the right plot in the picture below). Again, we have created a low pressure system with a similar overturning circulation as we saw in the tea cup.

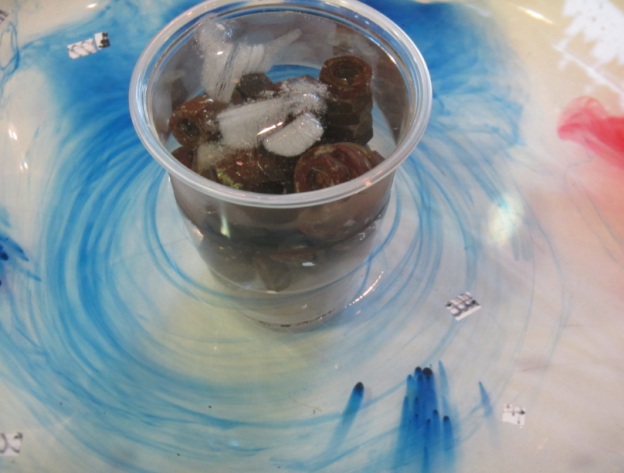

In the bottom right corner of the image above, we see a top view of the tank with the trajectory the dye is taking from the spot where it rested on the ground before the rotation of the tank changed.

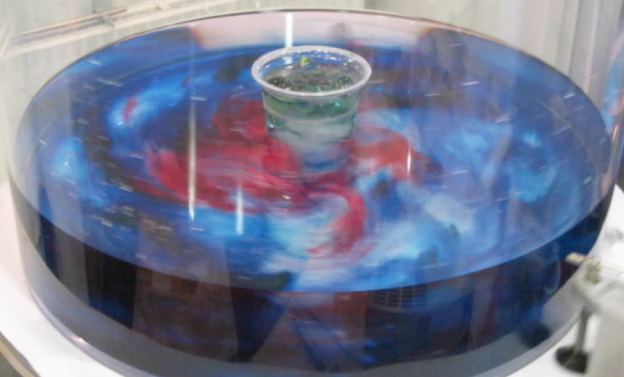

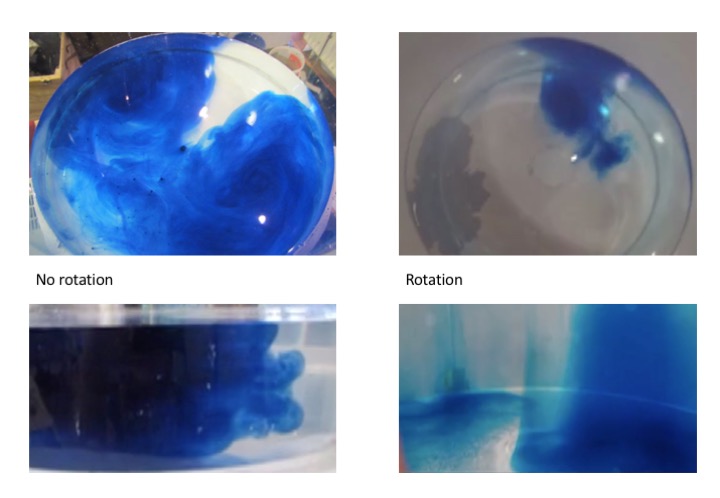

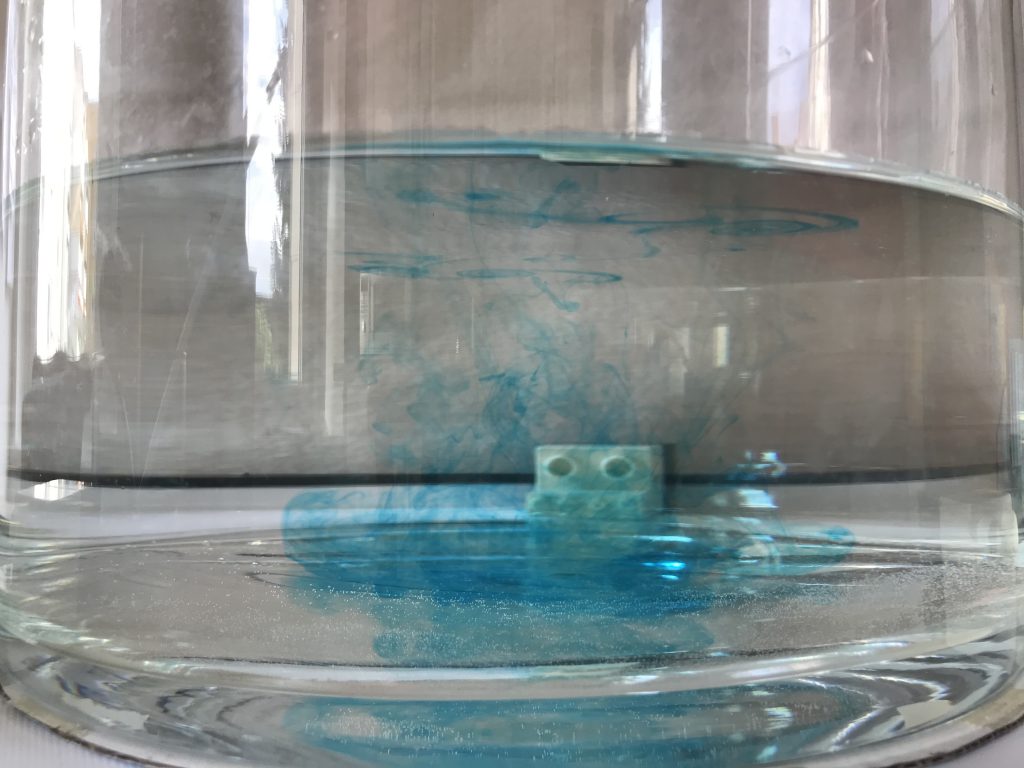

Looking into the tank with a co-rotating camera, we can also observe the Ekman depth, i.e. the depth that is influenced by the bottom: We see a clear distinction between the region where the dye streaks from the falling crystals are still vertical and the bottom Ekman layer, where they are distorted, showing evidence of the friction with the bottom.

So this was what happens when water is spinning relativ to a slower tank (or a non-rotating cup) — the paraboloid surface is adjusting to one that is more even or completely flat. But then there is also the opposite case.

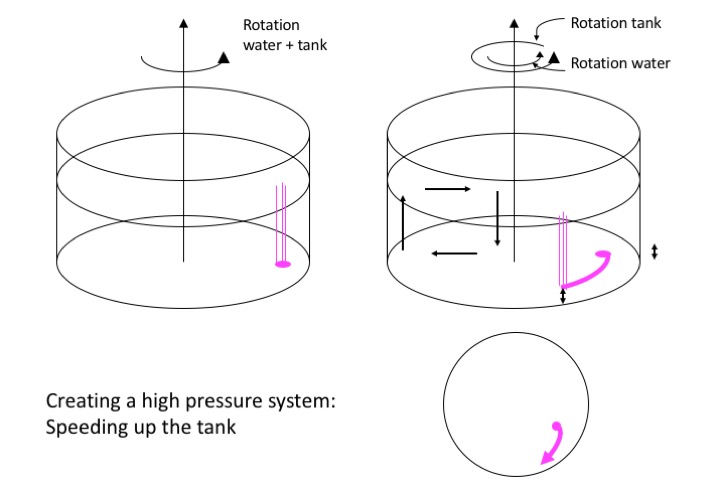

Creating a high-pressure system: Spinning up the tank

If we take water that is at rest and start spinning the tank (or spin a moving tank faster suddenly), we create a high pressure system until we again reach solid body rotation.

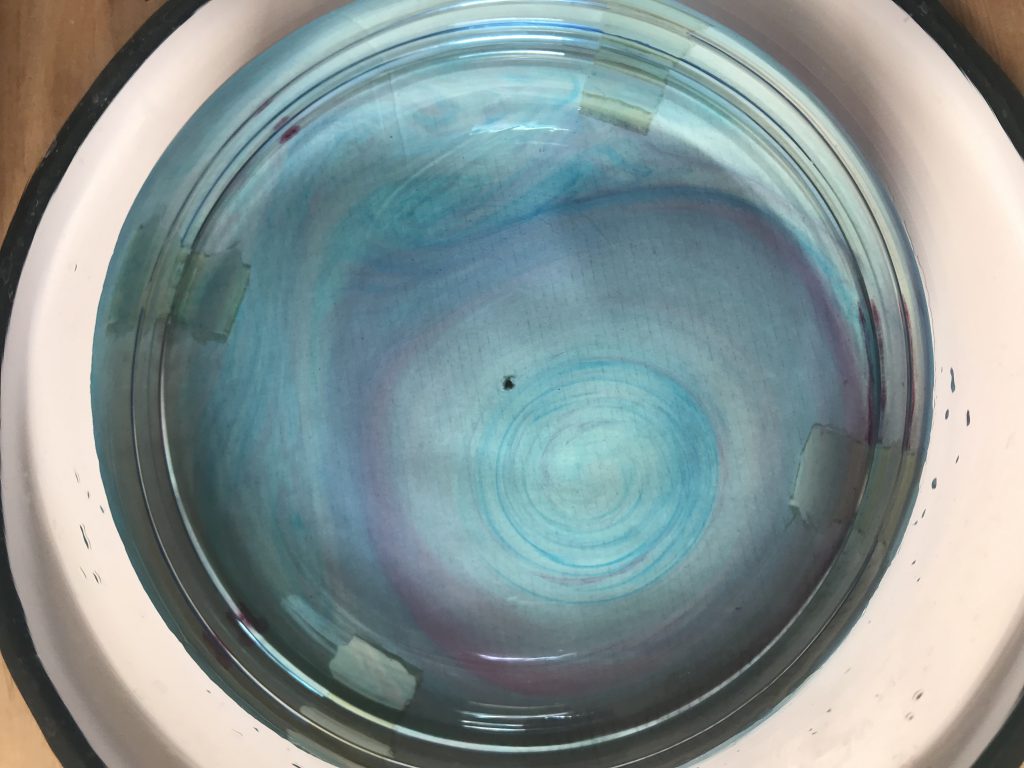

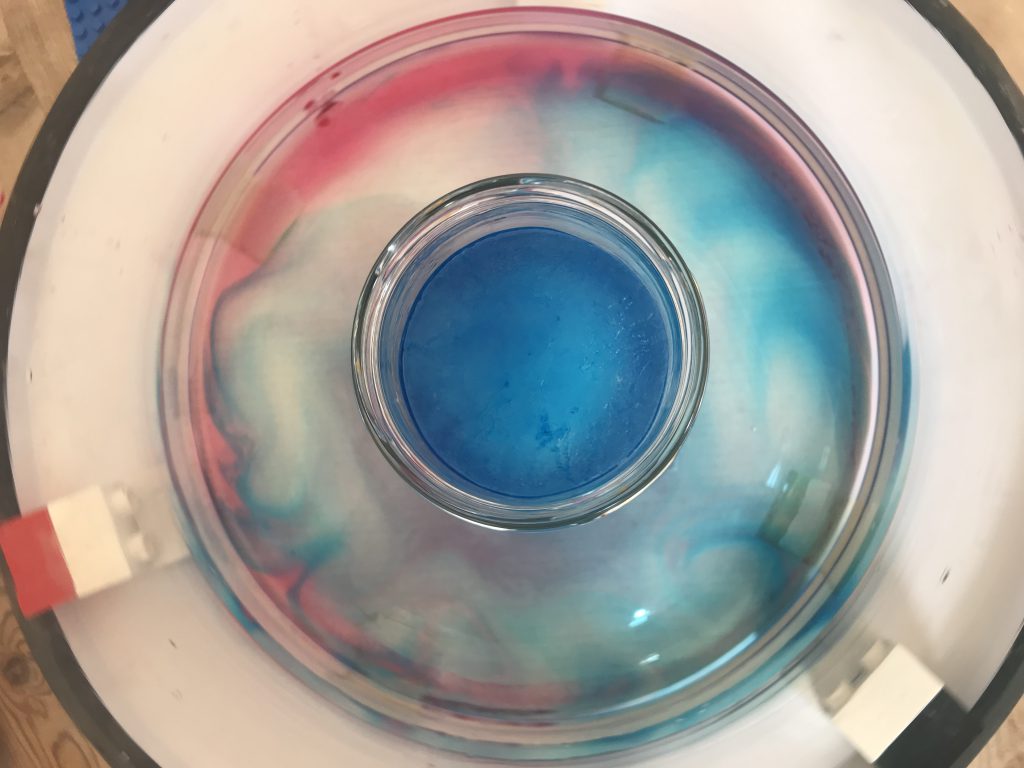

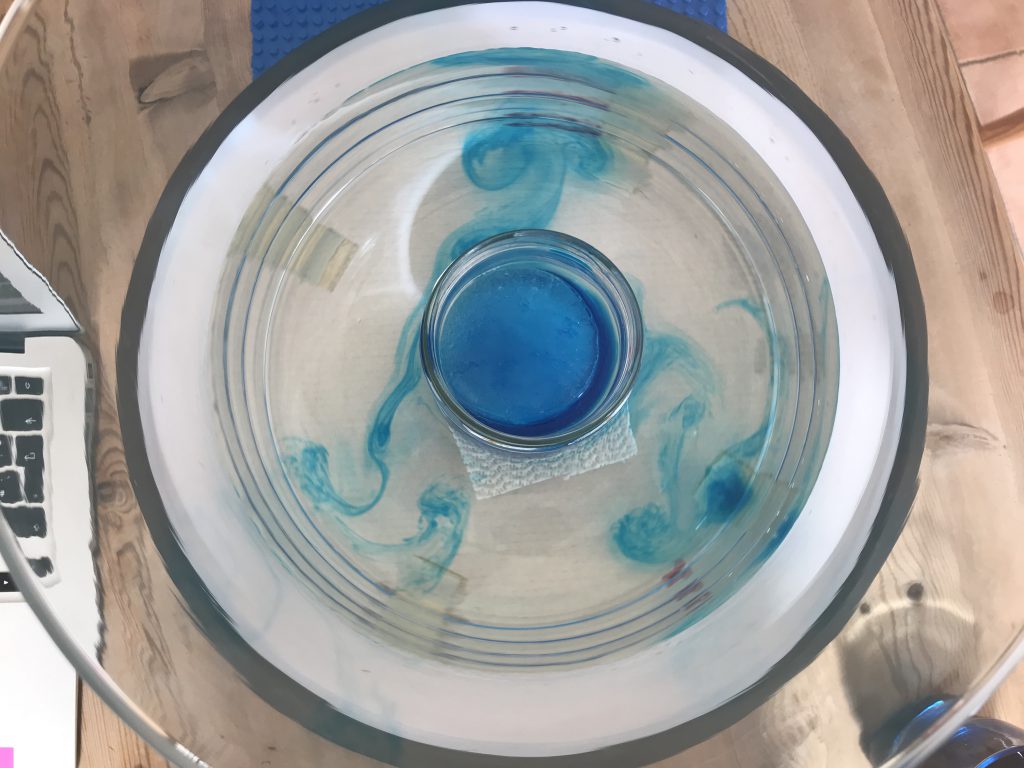

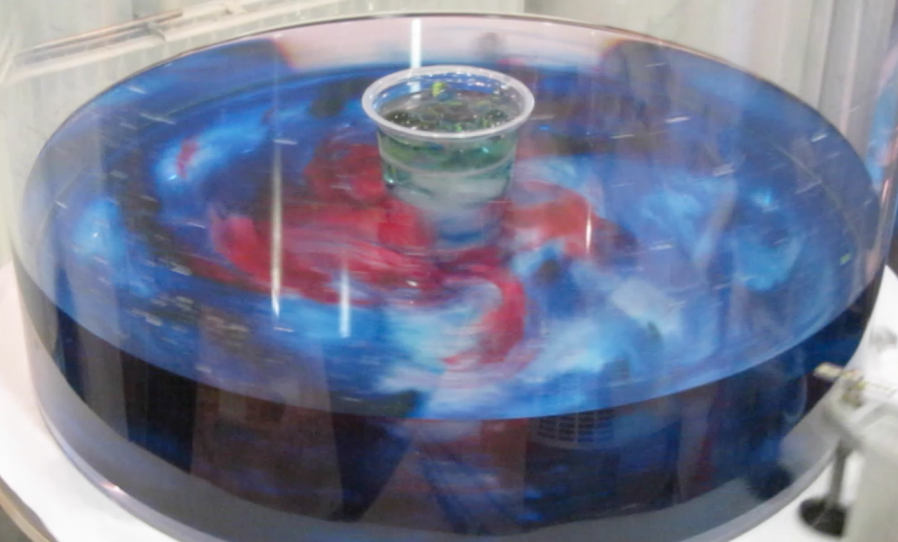

Again, we dropped dye crystals when the water was in solid body rotation (or in solid body without rotation) before we start the spinup, as we see in the left plot below.

Now the sudden spinning of the boundaries relative to the body of water creates a high pressure system with the bottom flow outward from the center, which again we see in the deformation of the dye streaks. The Ekman depth is again the depth over which the dye streaks get bent, below the water column that isn’t influenced by friction where they still have their original vertical shape.

In the bottom right corner of the image above, we see a top view of the tank with the trajectory the dye is taking from the spot where it rested on the ground before the rotation of the tank changed.

Here is what this experiment looks like in a movie:

So here we have it. High pressure and low pressure systems in a tank!

*Which I actually did before, both in a rotating tank as well as on a Lazy Susan.

To show the difference even more clearly, check out the movie below. Speed of both movies is the same!

To show the difference even more clearly, check out the movie below. Speed of both movies is the same!