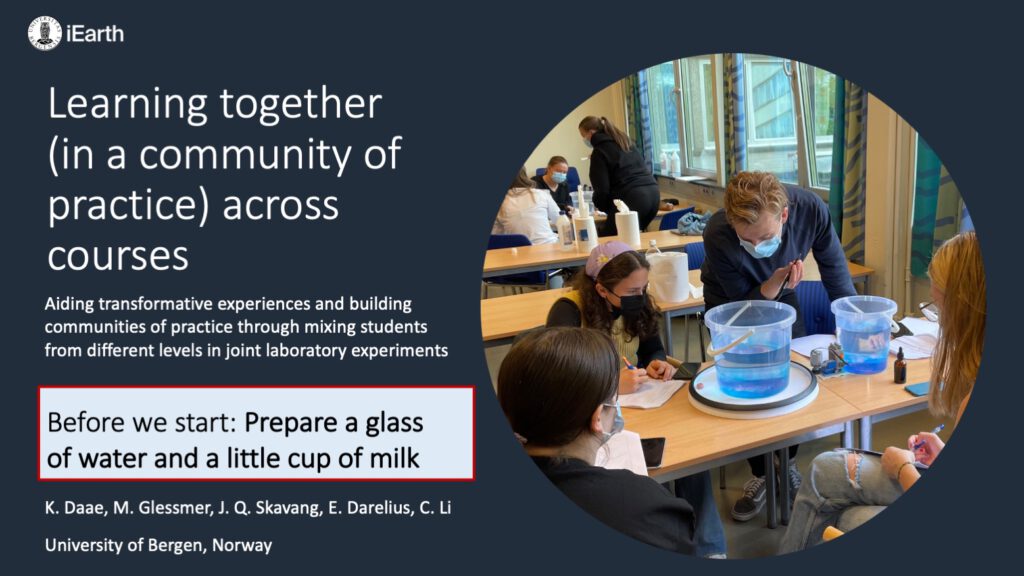

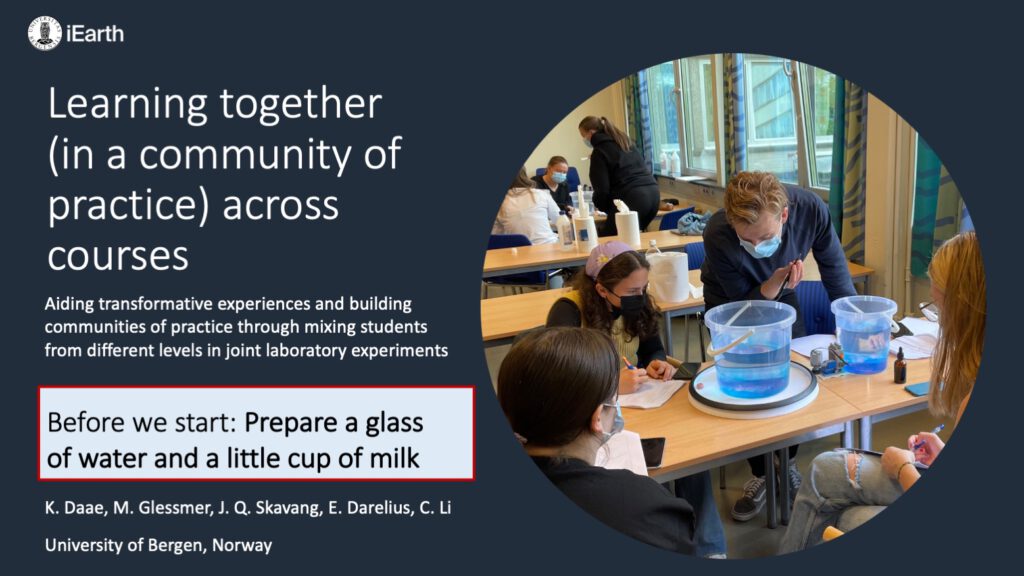

Last week, Kjersti Daae and I gave a virtual presentation at the iSSOTL conference, and here is a short summary.

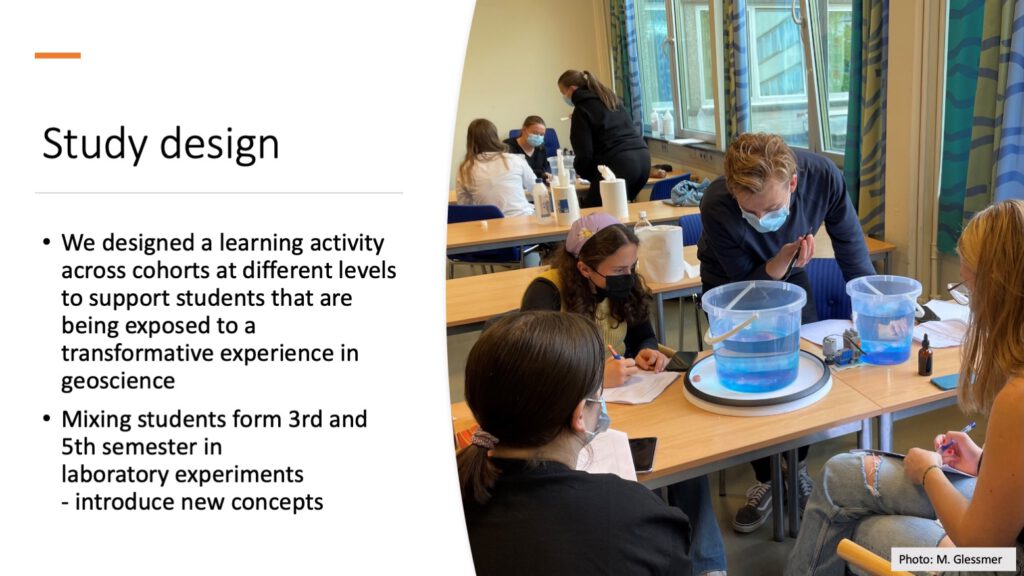

We presented an ongoing teaching innovation project, funded by Olsen legat and conducted together with Jakob Skavang, Elin Darelius and Camille Li, that we started last year at the Geophysical Institute in Bergen: Bringing together third semester and fifth semester students to do tank experiments.

In our presentation, we touched on the literature inspiring the design of the teaching project, the study we have conducted, and then our results and conclusions.

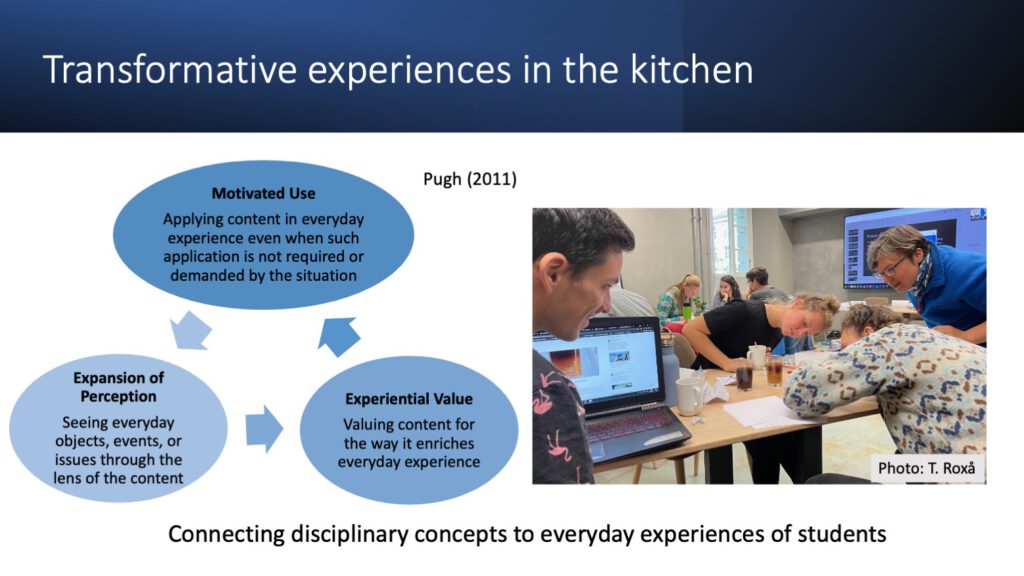

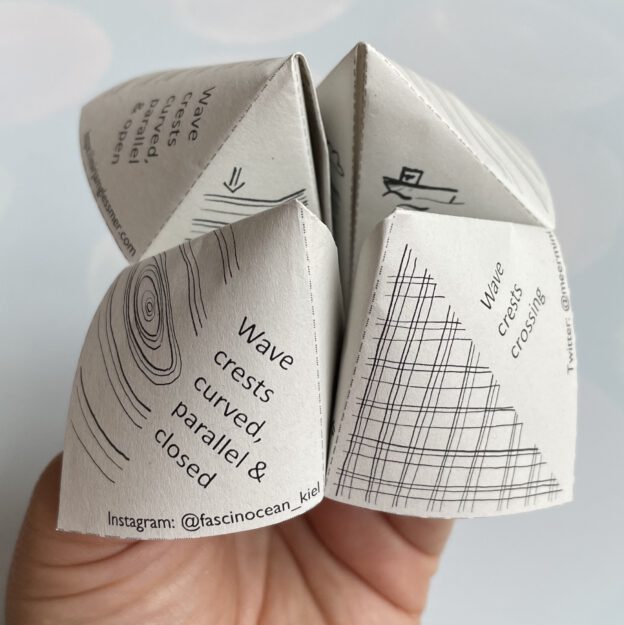

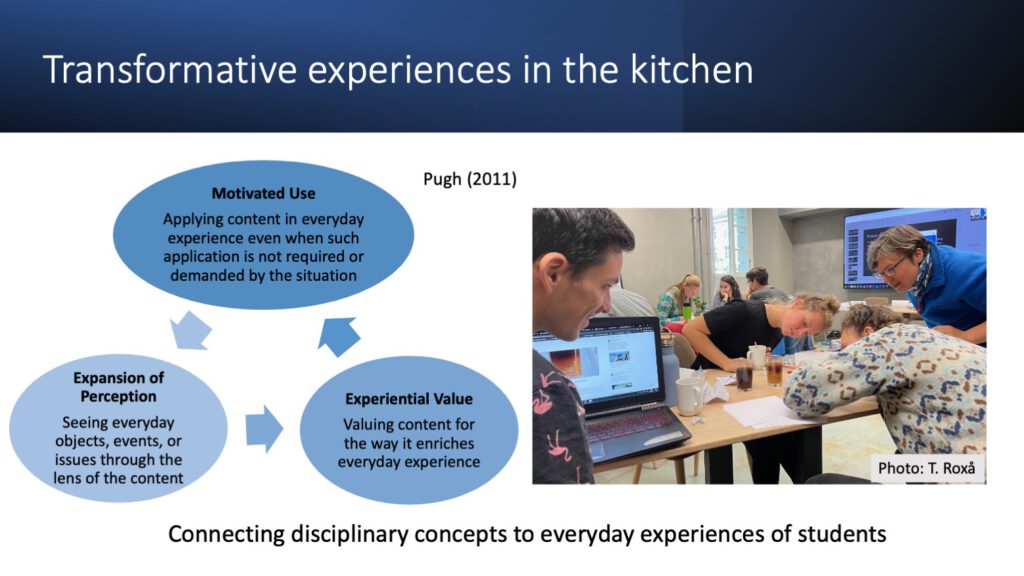

Our main goal was to change the way students look at the world around them, by giving them a new perspective on things. A framework that describes this well are “transformative experiences” that I wrote about in more detail here.

Transformative experiences are awesome, because they trap you in a feedback loop: Once you have changed the way you look at the world and notice new things, this feels good and makes life more fun. Therefore you continue doing it voluntarily, noticing more cool things in a new way, feeling happier about it, and so on and so on.

One example of a transformative experience happening was described by Dario after we did some kitchen oceanography (more on that here).

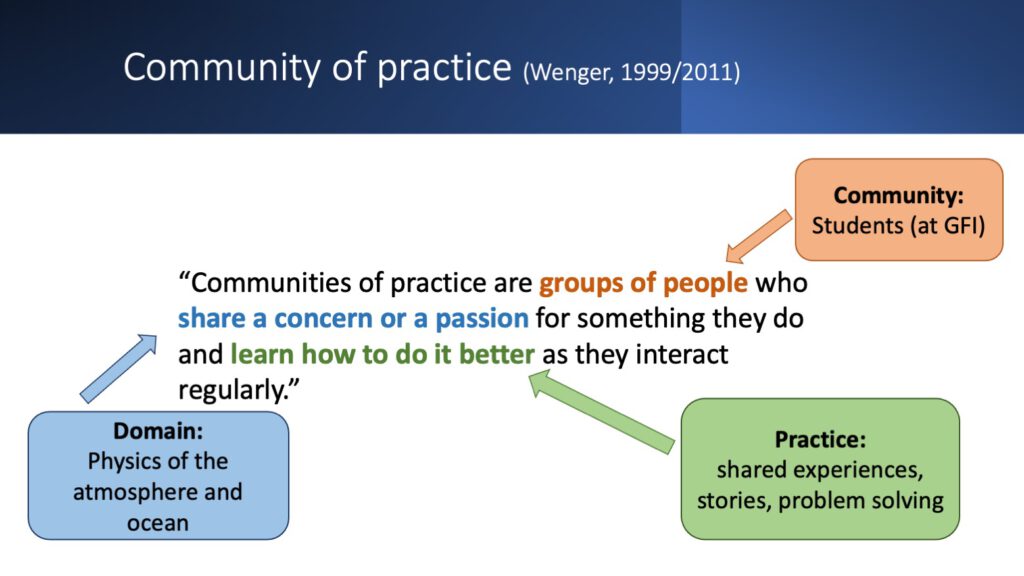

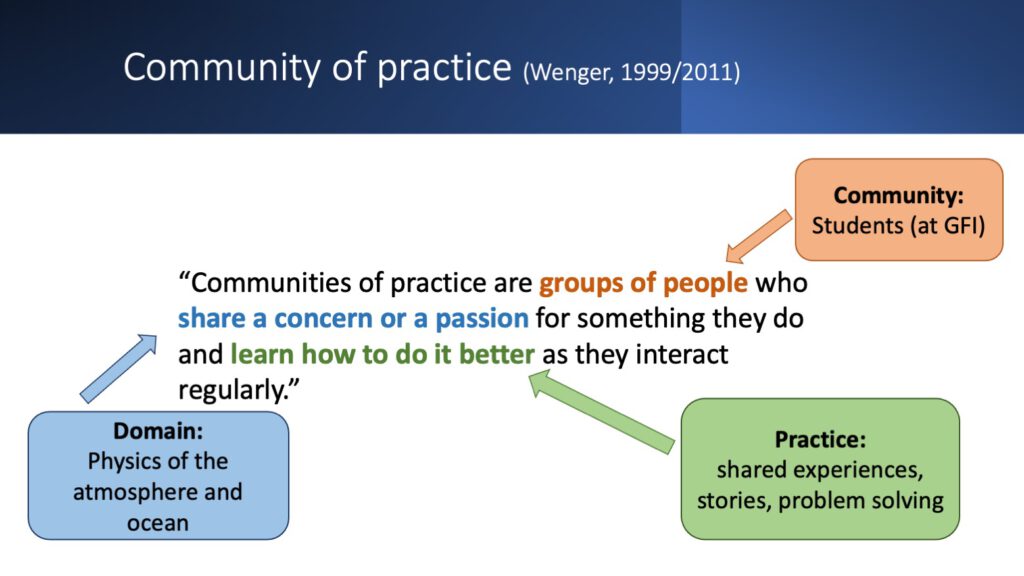

But we don’t want people to go through the transformative experience alone, we want them to do it in a community of practice to support one another and create even more of a feedback. In our case, the community are our students at the Geophysical Institute, who share the interest in dynamics of the atmosphere and ocean and learn more about them by having shared experiences and discussions that they can refer back to.

The topic we wanted to address in our course and make the central topic of this community of practice is the influence of rotation on movement in the atmosphere and ocean. This is the central concept of geophysical fluid dynamics, but it is difficult to grasp because the scales in question are so large that they are difficult to directly observe, and the mathematical descriptions are difficult and unintuitive.

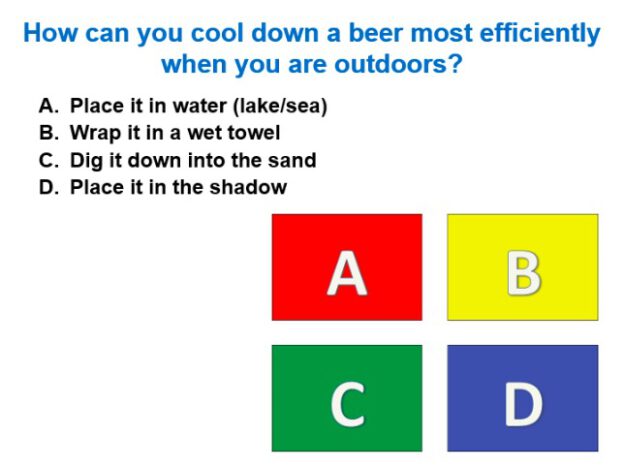

And here is where we invited the audience to become part of the very first steps in that teaching project.

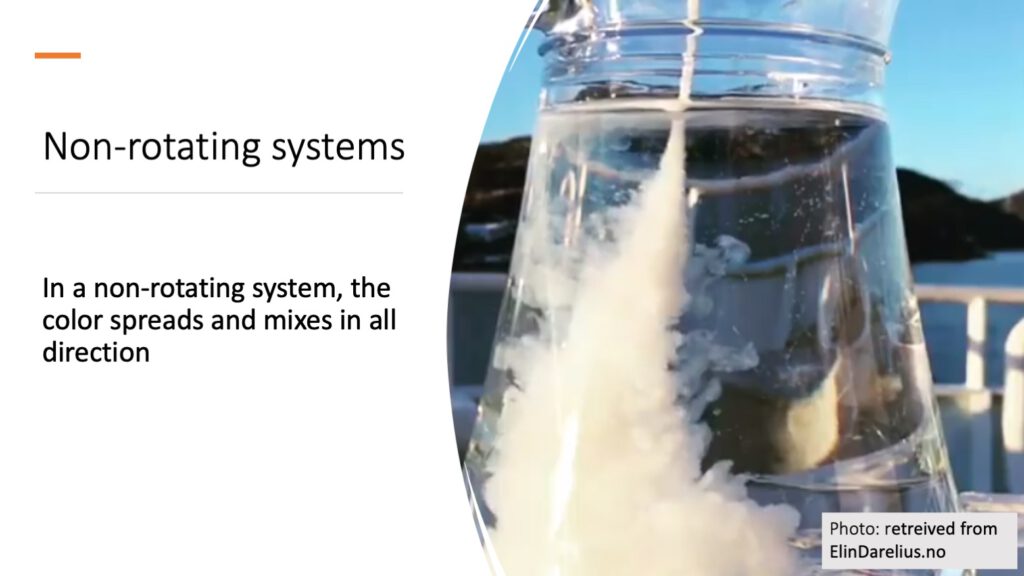

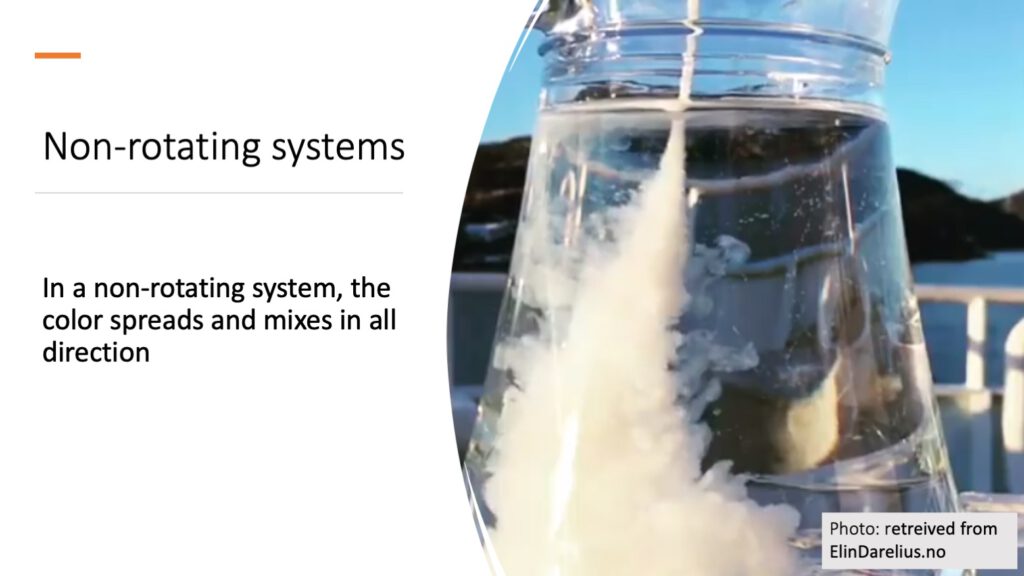

We start out by making sure everybody has a good grasp of what happens in a non-rotating frame so we can later contrast the rotating case to something we know for sure people have seen before (we used to assume that people had a good grasp of what happens in non-rotating fluids, but this turns out to be very much not the case).

At this point in our demonstration, Kjersti showed a live demonstration! (And I was so fascinated that I forgot to take a screenshot)

Once we have established what pouring a denser fluid into a lighter fluid looks like in a non-rotating case, it is time to move on to a rotating case. Considering rotation when we talk about flows on the rotating Earth (in the atmosphere or ocean) needs to consider that the Earth has been spinning for a very long time. We can simulate that by rotating a bucket of water (which needs to rotate for a much shorter period of time because it is much smaller).

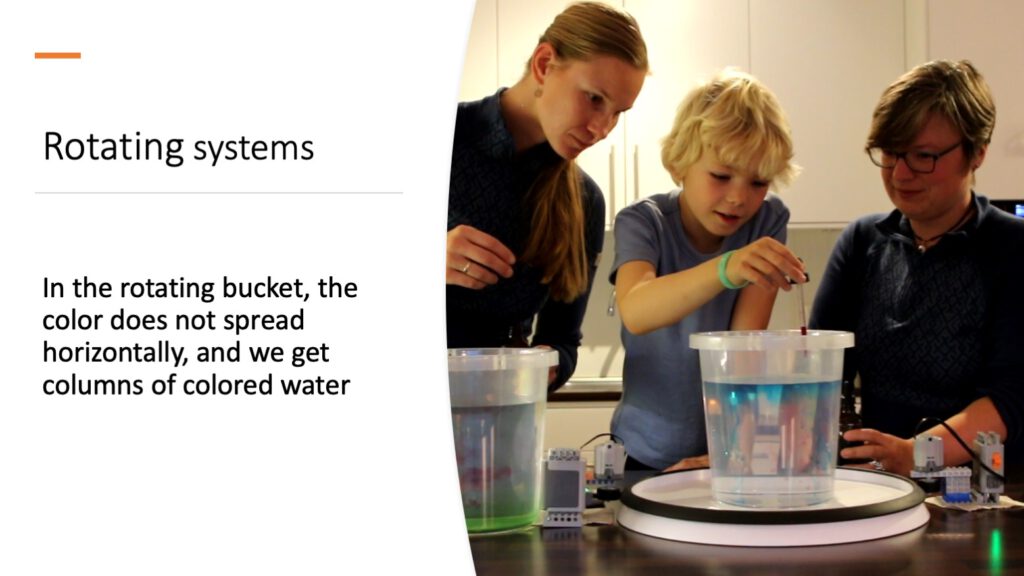

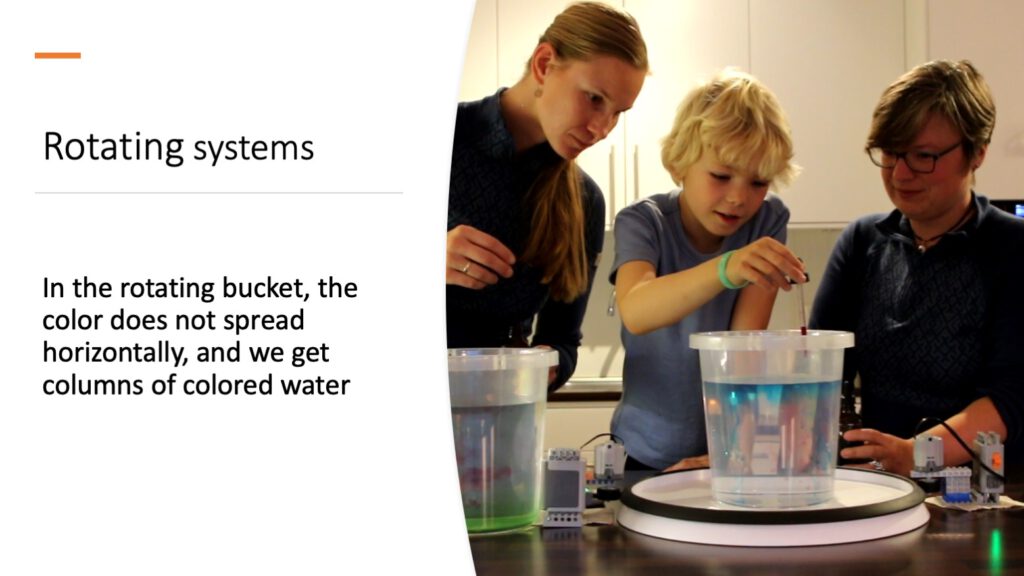

When we drip colour into a rotating bucket full of water, the way the colour distributes itself looks very different from what it looked like earlier in the non-rotating case. We now get columns of dye rather than the mushroom-like features.

These experiments are not difficult in themselves, but we wanted students to not just follow cookbook-style instructions, but to actively engage and discuss what they observe.

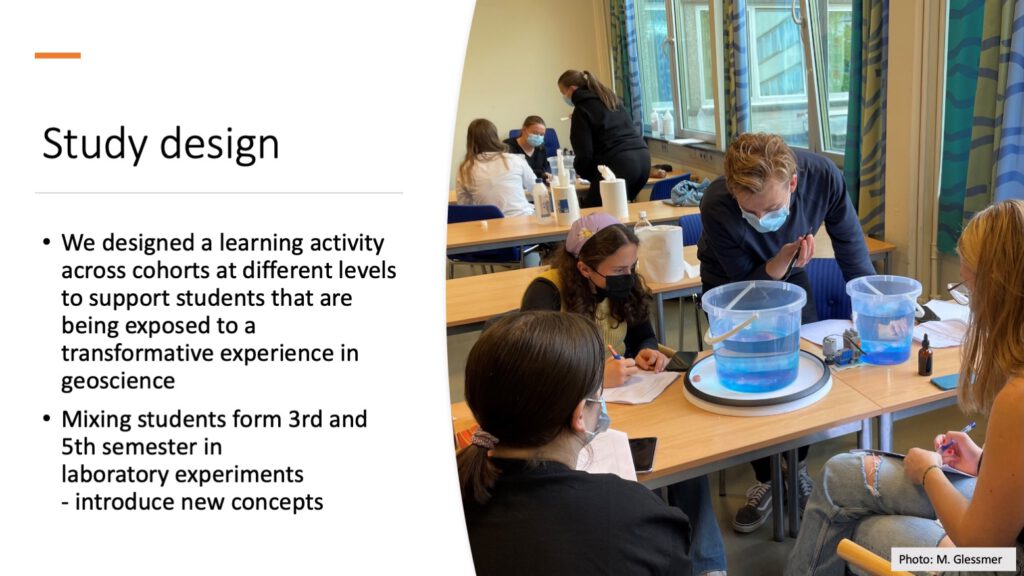

Therefore, we brought students in their third semester together with students in their fifth semester, who had done the same experiments in the previous year.

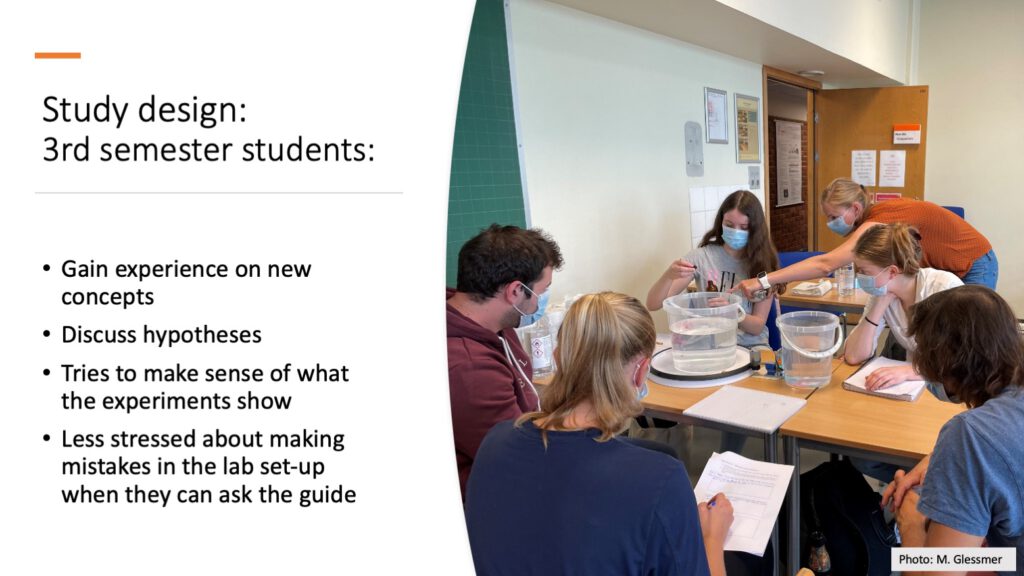

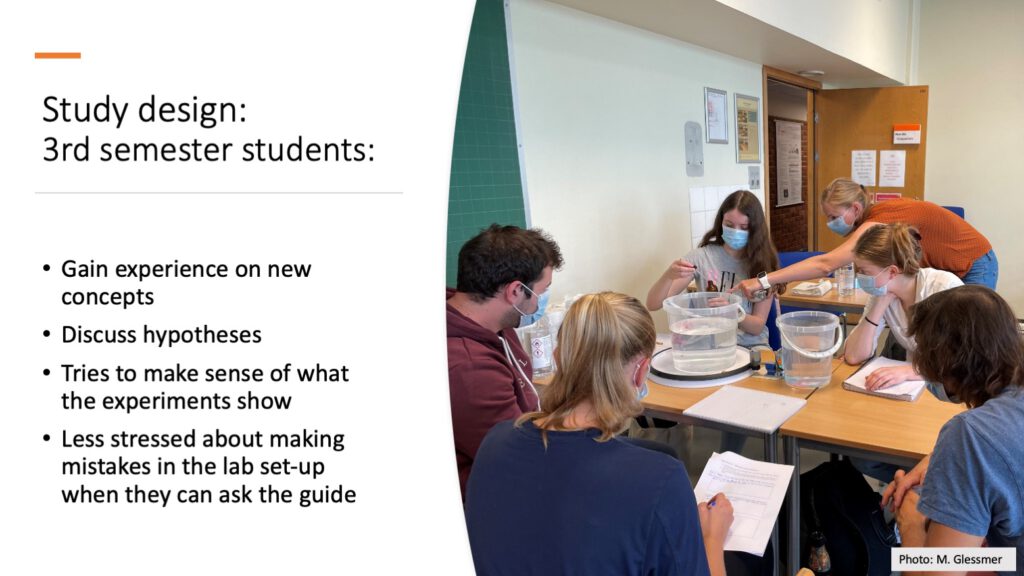

The idea was that the third semester students would receive guidance by the older students, and would be able to discuss hypotheses and make sense of their observations together. The presence of the fifth semester students would help them be less stressed about potentially making mistakes and help the labs run a lot smoother.

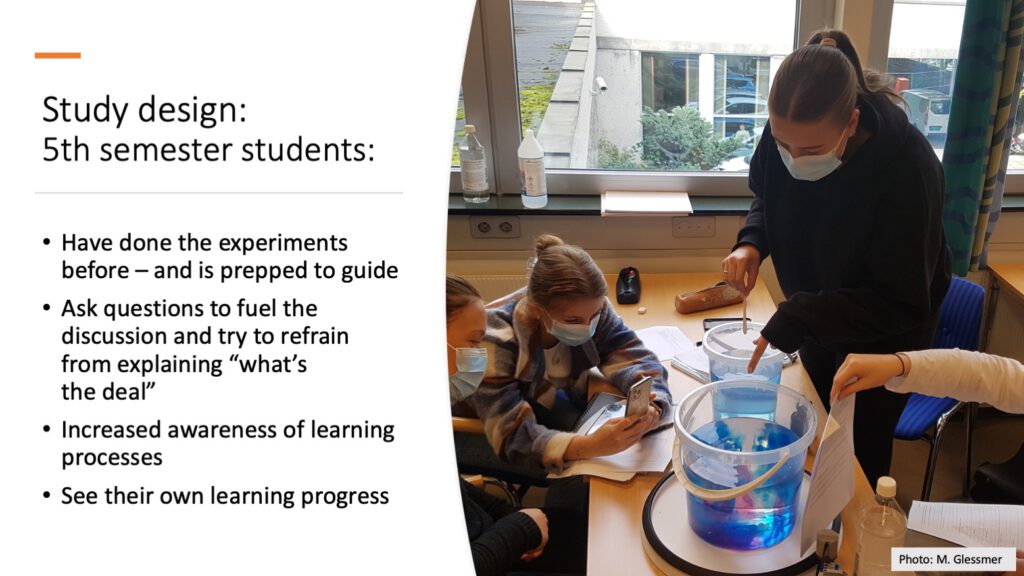

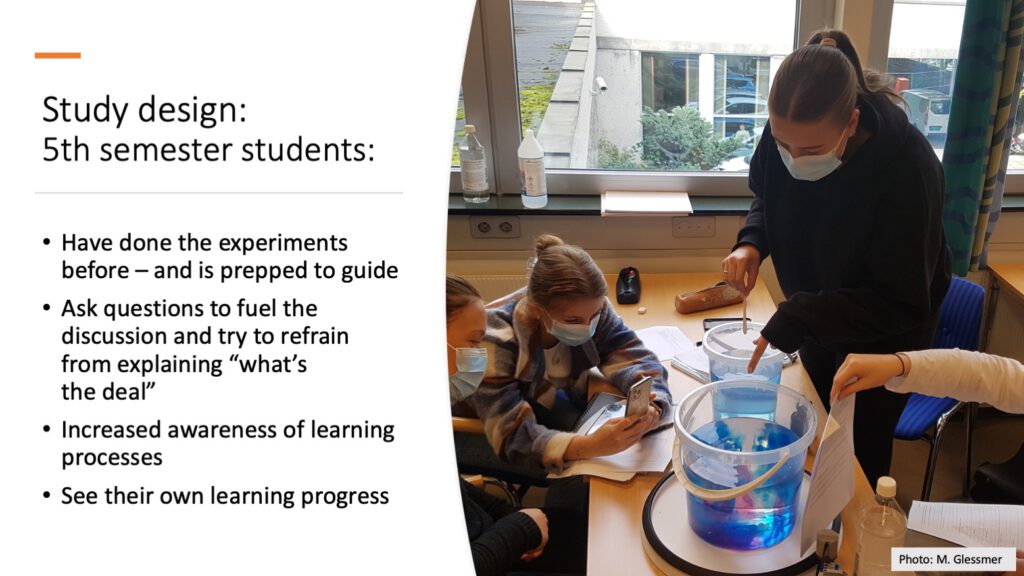

The fifth semester students had done the experiments in the previous year. We prepared them for their role (you don’t need to know all the answers! In fact, you are not supposed to even answer their questions. Help them figuring it out themselves by asking questions like “…”) and went through the experiments with them to refresh their memory and also talk about how they were understanding and seeing things differently now that they had another year of education under the belt compared to when they first saw the experiments.

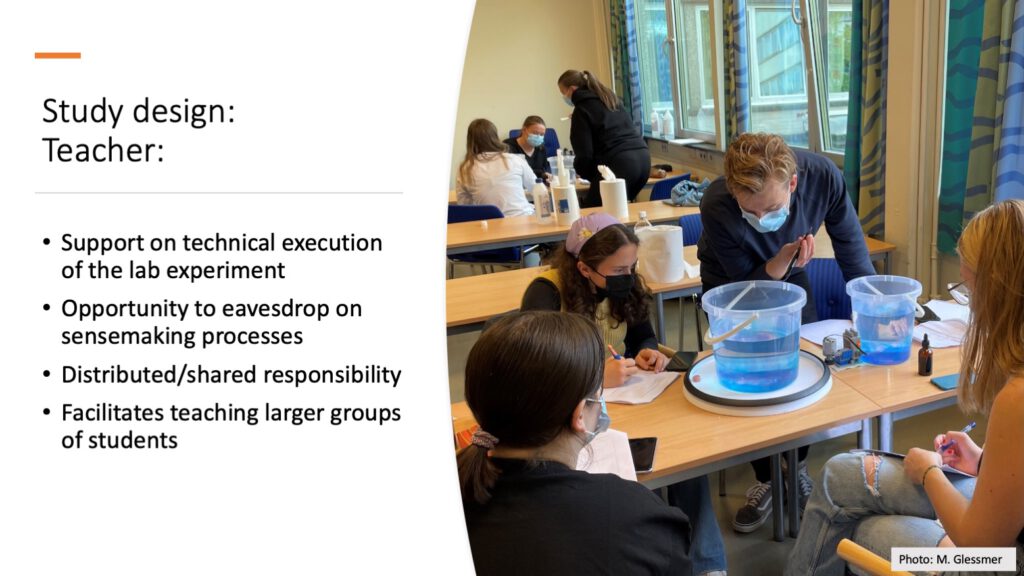

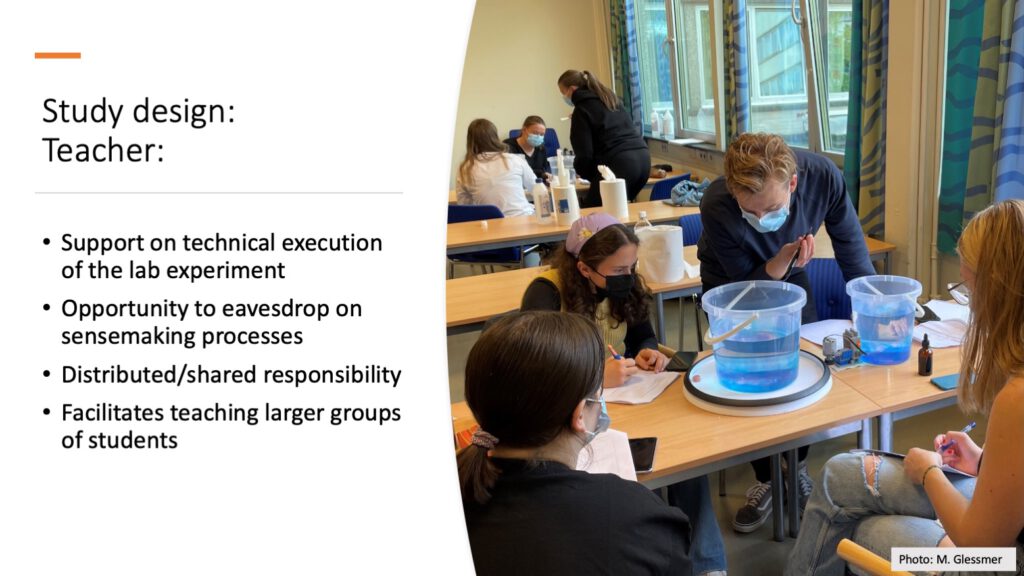

And then for us: Distributing and sharing responsibility for learning is something we have been interested in for a while now (see blog post on co-creation here for more information). Having students so engaged in sense-making through discussions gave us a great opportunity to eaves-drop on their arguments and get a much better understanding of what they are thinking and which points we should address in more detail later.

In order to understand how this setup worked for the students, we collected several types of data: We had questionnaires aimed at the third semester students (testing specific learning outcomes, but also on their observations of roles and interactions, and interpretations of the situation) and fifth semester students (on observations of roles and interactions, and interpretations of the situation, and how they would compare the experience as “guide” to that the previous year). We instructors also took notes and reflected on our observations.

So what did we find?

The third semester students all perceived the presence of the older students as very positive and described the interactions the way we had hoped — that they weren’t being fed the answers, but asked questions that help them find answers themselves.

From the fifth semester students, we also got a very positive response. They especially focussed on how they had to think about what makes a good question or good instruction, and that that helped them reflect on their own learning. They also pointed out that the experience showed them how much they had learned during the last year, which they had not been aware of before.

They also really enjoyed the experience of being a teacher and interacting in that role.

Also looking at learning outcomes, we found that the third year students learned a lot more as compared to last year’s third year students (which is a bit of an unfair comparison since last year was dominated by covid-19 restrictions, but still that is the only data we have that we can compare to). Specifically, the misconception that “the centre of the tank is the (North) Pole” seems to have been eradicated this year (we’ll see if that holds over time).

One thing we noted and that students also pointed out as very helpful is that conversations did not just deal with the experiment itself, but that the younger students asked a lot of questions about other experiences that the older students had made already, like for example the upcoming student cruise. We had hoped that this would happen, and that these kind of conversations would continue beyond these lessons!

So this is where we ended our presentation and hoped to discuss a couple of questions with the audience. If you have any input, we would love to hear from you, too!