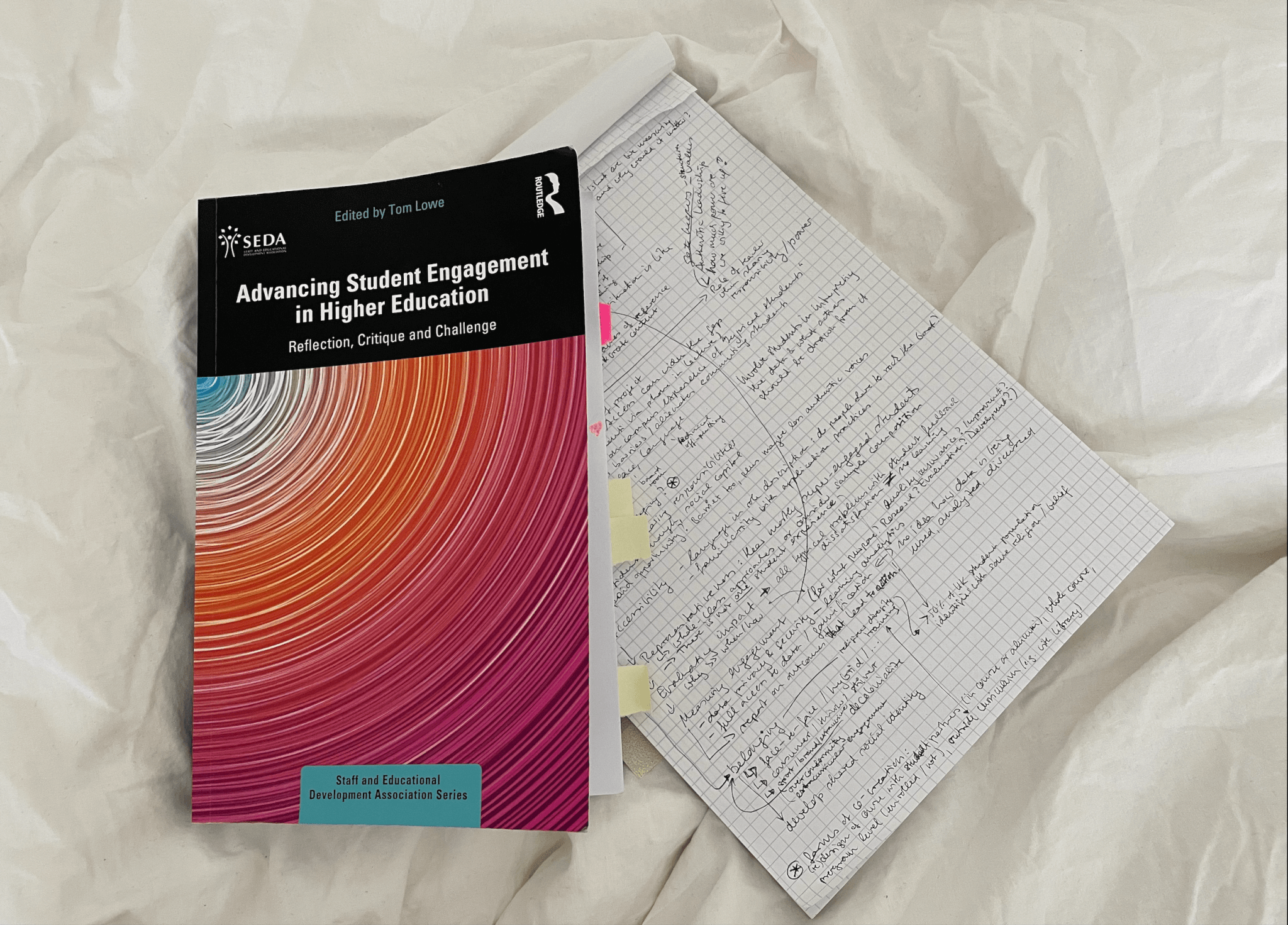

Currently Reading “Advancing Student Engagement in Higher Education: Reflection, Critique and Challenge” (Lowe, 2023)

Students can engage in higher education in different ways: behavioral, emotional, cognitive, or in any combination of those. Traditionally, this is seen as engagement with the curriculum inside the classroom, but increasingly the view of student engagement is widened to include forms where students take more ownership of their own learning, for example when becoming involved in (re)designing curriculum as student partners who are currently taking a course (or not), co-creating learning with a whole course, influencing learning on a program level (whether enrolled in the program or not), or influencing the bigger setting through engagement with services like university libraries, or in developing religious diversity training. In the book “Advancing Student Engagement in Higher Education: Reflection, Critique and Challenge”, Lowe (2023) brings together 25 chapters from 36 contributors, exploring and highlighting different aspects from very different perspectives. I am summarizing my personal main takeaways below.

In the discourse in educational development, working towards increased student ownership of their own learning is seen as generally positive, but it is necessary to reflect explicitly on our aims and the implications they have. We accept that students are experts on what it is like being a student right now. They are a different generation from back when we, their teachers, were students, with different lived experiences of major life events, some as disruptive as a global pandemic, different political and social conditions, and with different ways of creating and sharing content. Using this expertise can help us improve learning experiences and learning outcomes, but we can do that instrumentally to improve quality of education in a neo-liberal sense, or we can do it with the aim of liberating and empowering, welcoming different ways of knowing and diverse backgrounds. This is a challenge for us teachers: We are in a position of power, and we are gatekeepers of structures and values. How much responsibility are we really willing to share, how much power willing to give up?

As teachers, we have power not only to prescribe what is supposed to be learned, and assess whether it has been learned, but also to set the conditions in which the learning is to take place. Even when aiming to work in partnership with students, we can set the nature and scope of the partnership project, we can choose times, places, ways of communicating about the project that — to a larger or lesser extent — create barriers and alienate (a subset of) students. So we need to be aware of who we are implicitly inviting into cooperation: Only those who have a typical student experience on campus, or those without caring responsibilities, or those with enough confidence and social capital, those that are willing to rock the boat? Those who know how to write a traditional academic application? If we pay to level the playing field between students who can afford to spend time on working with us in our project, are we maybe building a different set of barriers for those students who cannot have paid employment due to e.g. immigration status, and does being paid influence what students feel can be said?

When it comes to the student voice that we hear, there is also the question of representativeness. It is likely that we hear most from the already highly engaged students, even though there is no such thing as one student experience, and a few, highly-engaged students might have very different experiences and opinions than many other students. Does that mean we should move towards whole-class approaches (but then what about students that explicitly do not want to engage in that way), or how else can we address “sample composition” to get a representative impression, without putting a burden on minorities to automatically become a spokes person?

And then, how do we know what impact we are having? When we start thinking about impact, we need to again be very clear about our aims with the whole project, but also with the evaluation itself. Are we doing it for quality insurance purposes, for research, for development? And in the light of how student engagement can be expressed, e.g. behavioral, emotional, cognitive, what kind of data can actually help us answer the questions we have? And are all students aware of what type of data we are collecting, how we plan to use, analyst and discuss it, and do we have their consent? Involving students in this part of a project seems crucial in order to interpret data correctly and to report on it and the actions that should be taken based on the outcomes in a way that is actually representative of how students think about it, yet this step that could be hugely empowering and liberating is often not taken.

Also, maybe barriers to student engagement that we should address are far outside of our own classroom, for example in extracurricular activities that we might over-emphasize in order to create a shared social identity and sense of belonging, yet that might demand an overconformity. Assumptions about who our students are and what matters to them can limit how welcoming we are towards, for example, the 50% of the UK student population that identifies with a religion or belief (a number that I would have guessed would be a lot lower). How can we make sure that all students experience ownership of their higher education experience, and feel empowered and liberated? This is where we as teachers need to commit to a reflective practice and come back to all the above, and more, questions, and critically reflect on our own role, how we lead, how we gate-keep. The book does give a lot of ideas for what we can try to adapt to our own context to work towards “advancing student engagement in higher education”, and it delivers on it’s subtitle of “reflection, critique and challenge”. It is definitely worth a read (and repeated long, hard, think)!

Lowe, T. (Ed.). (2023). Advancing Student Engagement in Higher Education: Reflection, Critique and Challenge (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003271789

[Edit 16.7.2024: A slightly more polished version of this has been published in the Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal as a book review: Glessmer, M. S. (2024), Book Review: Advancing Student Engagement in Higher Education: Reflection, Critique and Challenge, RAISE Student Engagement in Higher Education Journal, Vol. 5 No. 3, p 3-4, July 2024]

On all the levels of decision making when sharing responsibility for learning (after Heron, 1992) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] thinking a lot about how we want to share responsibility when co-creating, responsibility for what, and sharing with whom, and then Cathy recommended the Heron (1992) chapter “The politics of facilitation: Balancing […]