The Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome taxonomy.

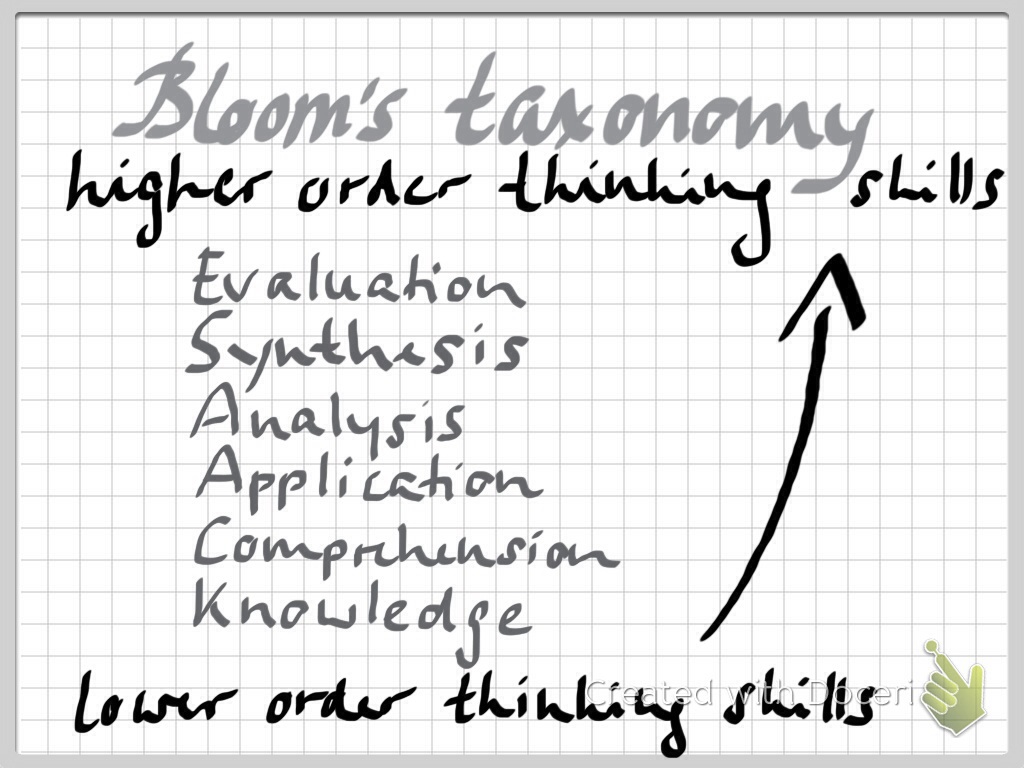

I talked about the classification of learning outcomes according to Blooms’s taxonomy recently, and got a lot of feedback from readers that the examples of multiple-choice questions at different Bloom-levels were helpful. So today I want to present a different taxonomy, “Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome”, SOLO, this one classifying the structural complexity of learning outcomes.

SOLO has first been published in 1982 by Biggs and Collis, and the original book is sadly out of print (but available in Chinese). There is a lot of material out there that either describes

SOLO or

applies it to teaching questions, so you can get a quite good idea of the taxonomy without having read the original source (or so I hope ;-)).

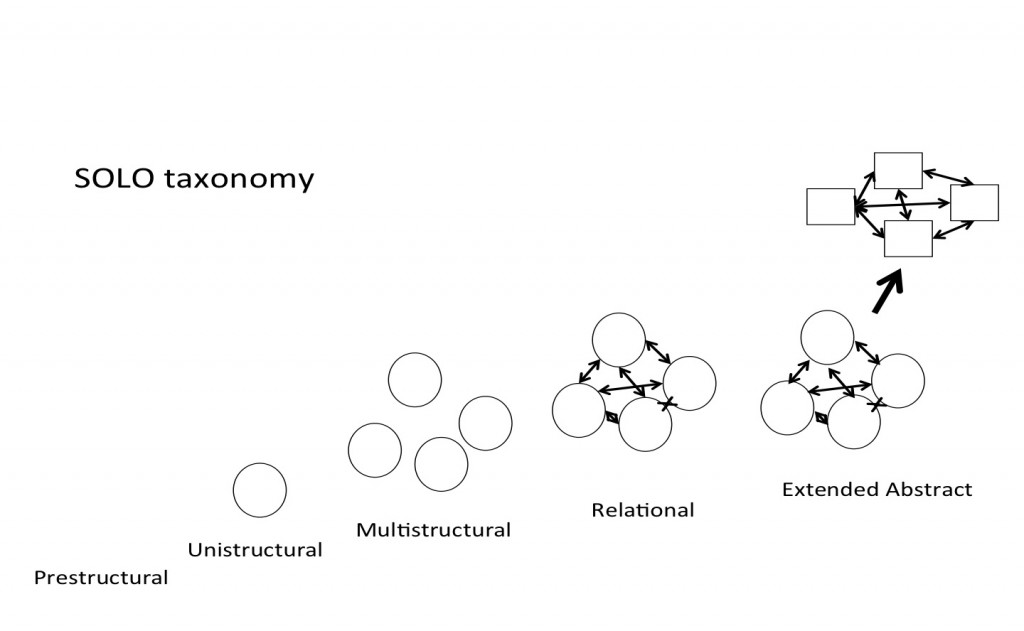

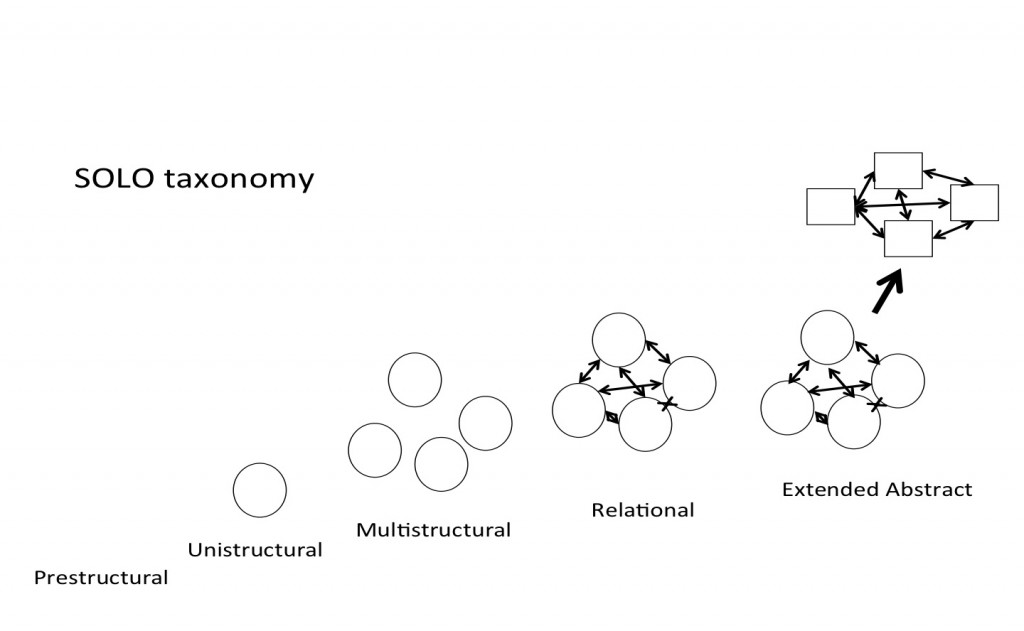

SOLO has four levels of competence: unistructural, multistructional, relational and extended abstract. At the unistructural level, students can identify or name one important aspect. Multistructural then means that the student can describe or list several unconnected important aspects. At the relational level, students can combine several important aspects and analyze, compare and contrast, or explain causes. Lastly at the extended abstract level, students can generalize to a new domain, hence create, reflect or theorize.

Visualization of the different levels of competence in the SOLO taxonomy

While competence is assumed to increase over those four levels, (in fact, there is a fifth, the prestructural, level before those four levels, where the student has completely missed the point), difficulty does not necessarily increase in a similar way.

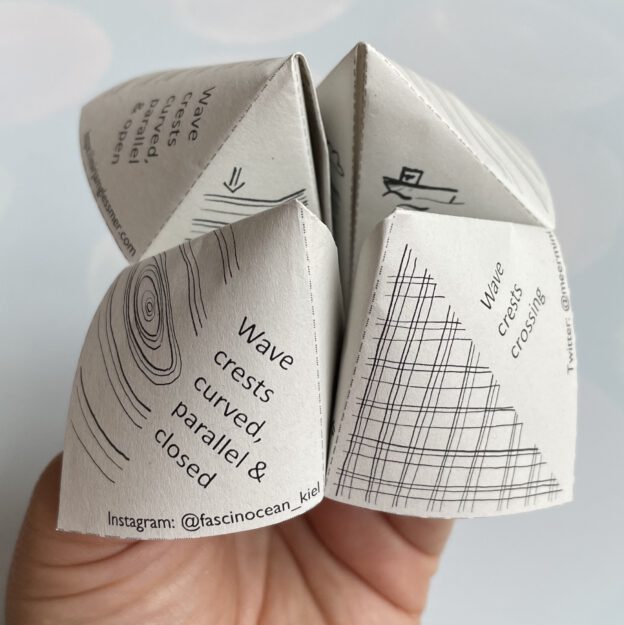

Depending on how questions are asked, the level of competence that is being tested can be restricted. I am going to walk you through all the levels with an example on waves (following the mosquito example here). For example, asking “What is the name for waves that are higher than twice the significant wave height?” requires only a pre-structural response. There is basically no way to arrive at that answer by going through reasoning at a higher competence level.

Asking “List five different types of waves and outline their characteristics.” requires a multi-structural response. A student could, however, answer at the relational level (by comparing and contrasting properties of those five wave types) or even the extended abstract level (if the classification criteria were not only described, but also critically discussed).

A higher SOLO level would be required to answer this question: “List five different types of waves and discuss the relative risks they pose to shipping.”

At worse, this would require a multi-structural response (listing the five types of waves and the danger each poses to shipping). But a relational response is more likely (for example by picking a criterion, e.g. wave height, and discussing the relative importance of the types of waves regarding that criterion). The question could even be answered at the extended abstract level (by discussing how relevance could be assessed and how the usefulness of the chosen criteria could be assessed). Since the word “relative” is part of the question, we are clearly inviting a relational response.

In order to invite an extended abstract response, one could ask a question like this one:

“Discuss how environmental risks to shipping could be assessed. In your discussion, use different types of waves as examples.”

Is it helpful for your own teaching to think about the levels of competence that you are testing by asking yourself at which SOLO level your questions are aiming, or do you prefer Bloom’s taxonomy? Are you even combining the two? I am currently writing a post comparing SOLO and Bloom, so stay tuned!