Do you sometimes feel that wherever you go, you just happen to observe something that makes you think about physics? I definitely do, and that’s what happened to me again this Sunday.

#diwokiel — one week full of exciting events related to digitalization of the world

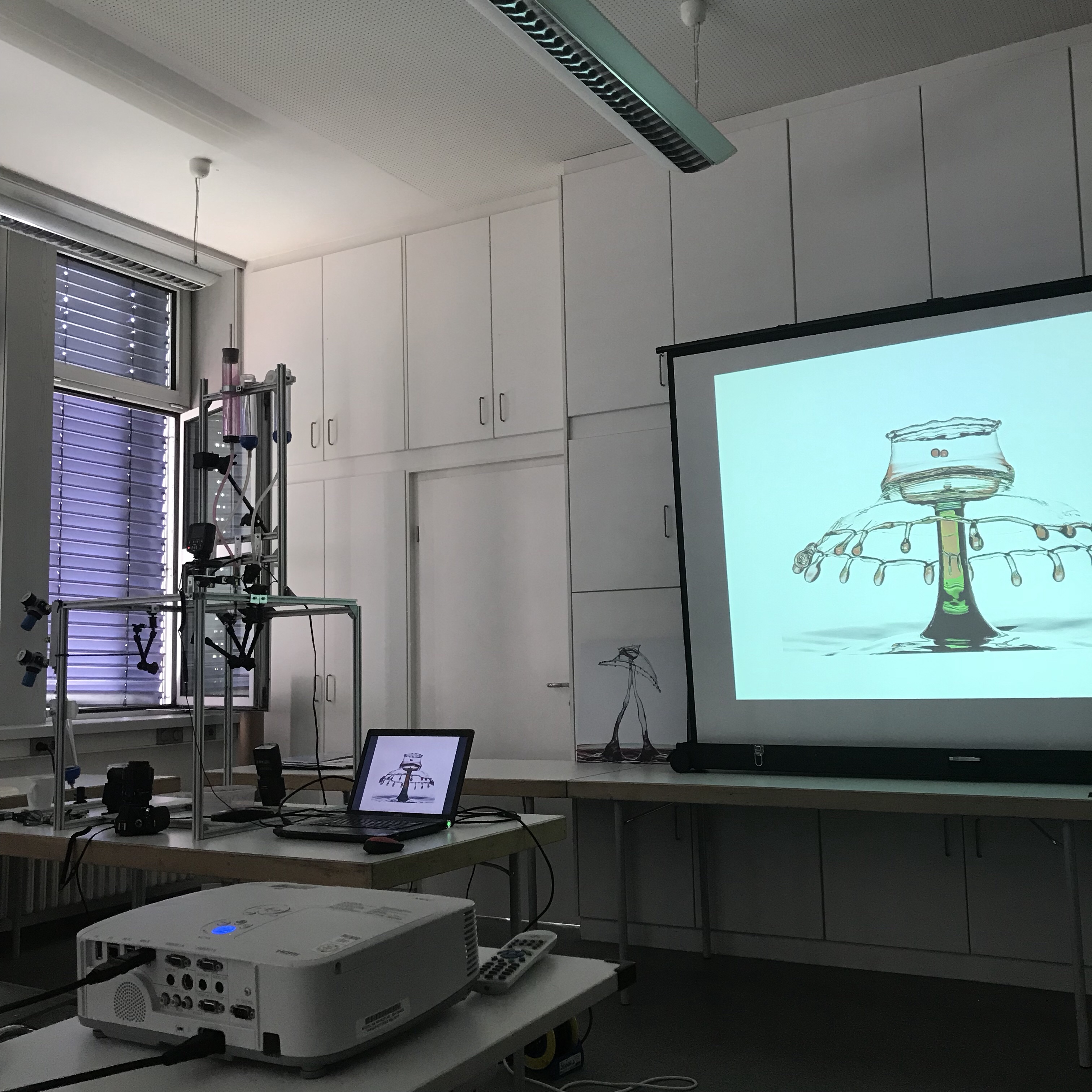

It’s currently #diwokiel, a week-long event on all kinds of aspects of digitalization. I went to a talk on his “liquid art” by Wlodek Brühl. Mr. Brühl forms sculptures out of water drops and documents those sculptures through photography. But “forming sculptures” really doesn’t begin to convey the process through which this happens and the level of expertise and precission that is needed. Below, you see an example of one of his sculptures on the projection (for more of his absolutely breath-taking art, check out the portfolio on his website!), and the apparatus with which this kind of art is generated on the left.

As you might been guessing from the kind of setup already, there is an enormous amount of physics that goes into creating this kind of sculptures!

Using art as a hook to talk about physics

And we are back to a favorite topic of mine: How to use art in science communication!

One challenge that science communiction faces is how to reach audiences that aren’t already interested in what you want to talk about. Yes, school kids are often exposed to all kinds of topics in science communication events whether they are interested in them or not, just because their teacher decided they had to go there. But what about adults? There are a lot of people that would never knowingly attend an event that will deal with physics. Attracting them with something they are interested in — art, in this case — might be a great way to spark their interest in physics topics!

What’s the physics behind “liquid art”?

But where exactly is the physics that can be talked about? There are two main areas that jump at me: The physics of the water that is used to form the sculptures, and then the physics of capturing pictures and everything related to that.

Physics of water

As you might have guessed, my main interest lies in the physics of the water. How do you manipulate water to design exactly the kind of sculpture you want? This is not only about the exact size of drops, falling from the correct height, hitting a reservoir in the correct spot, at exactly the time you think it will, potentially additional drops with precisely calculated time lags…

In the following, I am going to give you three examples of the kind of physics I would talk about if I were to use “liquid art” in a science communication context. For all of these, there are so many nice hands-on experiments that could be offered to let people experience the effect of various parameters to show how and why it is important to consider them when creating drop sculptures. So exciting! :-)

Viscosity, or how to control the behaviour of drops

Firstly, viscosity. Having a handle on viscosity doesn’t only determine the size of the drops, but also the kind of behaviour that is displayed when the drop hits the reservoir — how deep will a drop sink, what kind of bubble will be formed, how high will the stem rise from the reservoir when surface tension drives it back up, all the good stuff.

Viscosity can be manipulated several ways: By manipulating the viscosity of water by adding starch or other substances, by using different fluids than water (which comes with additional problems, e.g. cleaning the apparatus afterwards), and by using different fluids and adding stuff to them. And then viscosity is also a function of temperature, so temperature of the whole lab (or studio) has to be controlled.

Hydrostatic pressure “plus”

The size of drops is also determined by another factor: By the hydrostatic pressure in the reservoir that feeds the drip (or valve) in combination with the opening time of said valve. There are very interesting ways to control the pressure in the reservoir that I could (and probably will ;-)) write several blog posts on!

And then it’s not only the hydrostatic pressure that is relevant: If several valves are used because water is coming from several reservoirs (for example because the water is dyed in different colors or because fluids of different viscosities are combined in one sculpture), adding pressure to a valve that is moved slightly out of the vertical lets you manipulate the parabolic trajectory the drop takes when falling, thus making it possible to drop on the spot exactly underneath a valve that just lets drops fall out vertically.

Waves, or symmetry of sculptures

And then, of course, you have to consider the vessel the water drops into. If that reservoir isn’t circular and the drop doesn’t hit it right in the middle, it is very difficult to create symmetric sculptures because the waves radiating from the point of impact (both on the surface and as pressure waves in the water) will, after being reflected by the rims of the reservoir, reach the mid point at different times, leading to an asymmetrical pressure field which will skew the whole sculpture.

Liquid art: Wlodek Brühl manipulating the apparatur he uses to create the amazing drop sculptures. Used with permission.

Physics of capturing images

And then, of course, there is all the physics of actually capturing the images. For example, Mr. Brühl mentions that the picture isn’t made by the camera, it’s made by the flash light. The way the pictures are taken that the camera’s exposure is actually fairly long, but the sharp definition is achieved because the flash only lights the sculpture for an extremely short time. And then there are things to consider like at what angle the flash lights the sculpture, how to achive the desired color effects, and many more. And of course writing the software that controlls all this!

More about this in a future post!