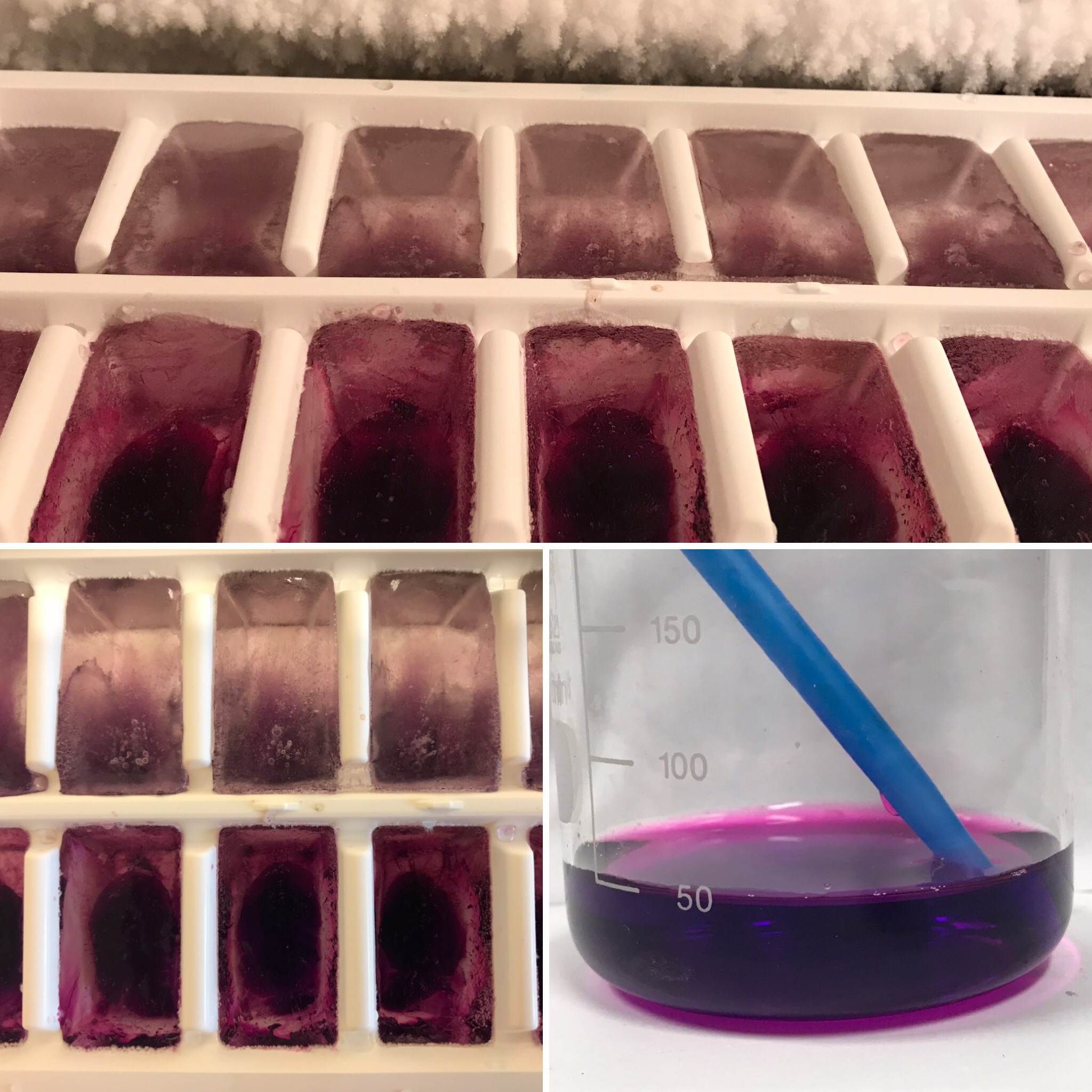

Many of my kitchen oceanography experiments use dyed ice cubes, usually because it makes it easier to track the melt water (for example when looking at how quickly ice cubes melt in freshwater vs salt water, or for forcing overturning circulations).

But the dyed ice cubes tell interesting stories all by themselves, too!

Salt water doesn’t freeze

“Salt water doesn’t freeze”? Then how do we get sea ice in the Arctic, for example?

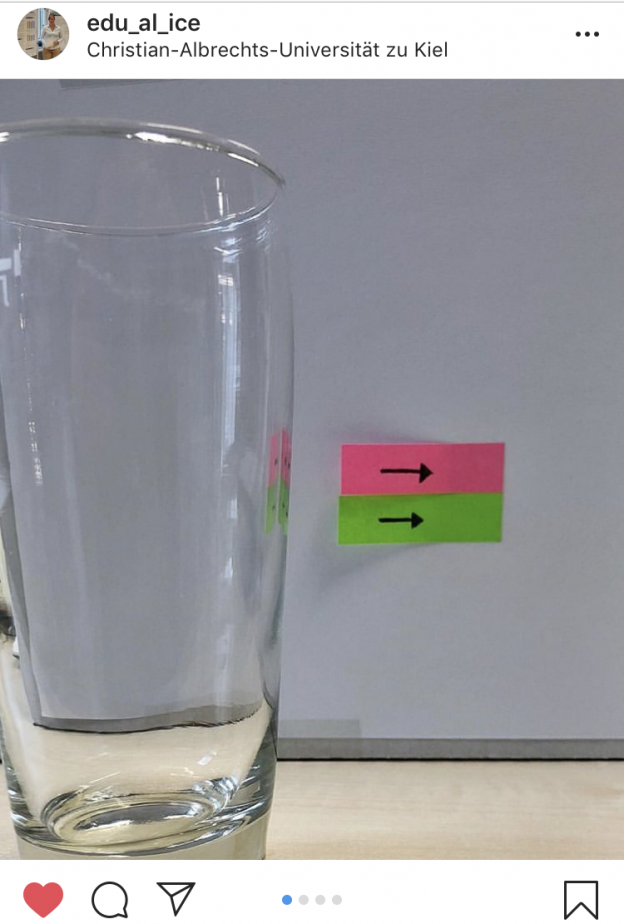

When freshwater freezes, the water molecules arrange in a hexagonal crystal structure. If there is salt (or anything else) in the water, however, the ions don’t fit into the regular structure. Ice freezes from the water molecules, and all the disturbances like salt get pushed in the last remaining bits of liquid water, which therefore gets higher and higher concentrations of whatever was dissolved in it. As those little pockets with high concentrations of salt get cooled further, more and more water molecules will freeze to the surrounding freshwater ice, leading to even higher concentrations of salt in the remaining liquid water. So the freshwater is freezing, while rejecting the salt.

Of course if you cool for long enough, also the last bit of remaining water will freeze eventually, but that takes surprisingly long (as you can try by freezing salt water in some of the cups ice cube trays and freshwater in others, for comparison. Also the structures of freshwater vs saltwater ice look very different and are interesting to look at, see how here).

“Brine release”

When the ocean freezes, this rejection of high-salinity water leads to interesting phenomena: Even when you melt it again to include all the pockets of high salinity water, sea ice will have salinities way lower than the water it froze from. This is because of a process called brine release. Since you are cooling the ocean from above, sea ice also forms from the surface downwards. This means that it is easy for the salty water to be pushed, “released”, or “rejected”, downwards, into the liquid ocean below. That ocean will then of course get more salty right below the ice!

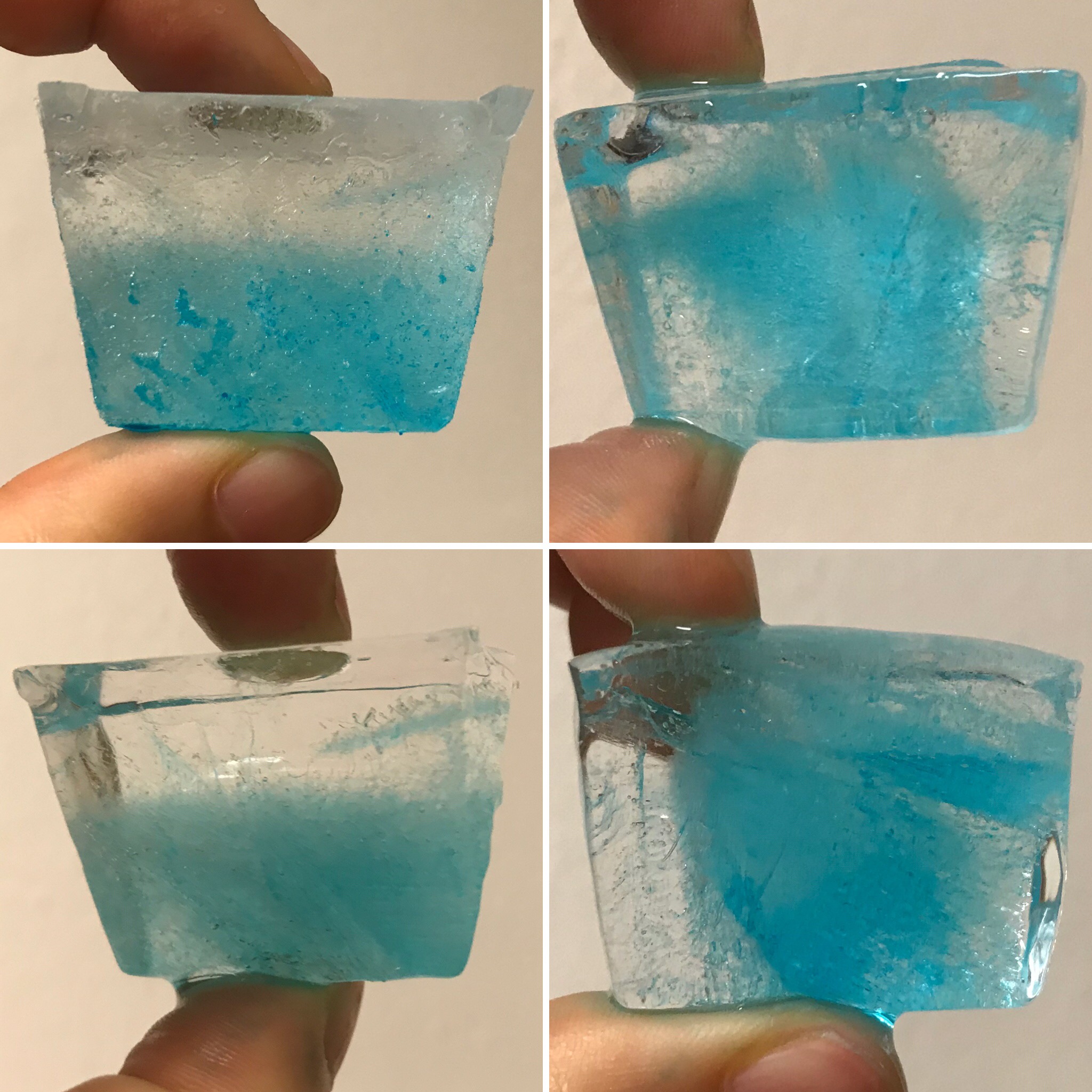

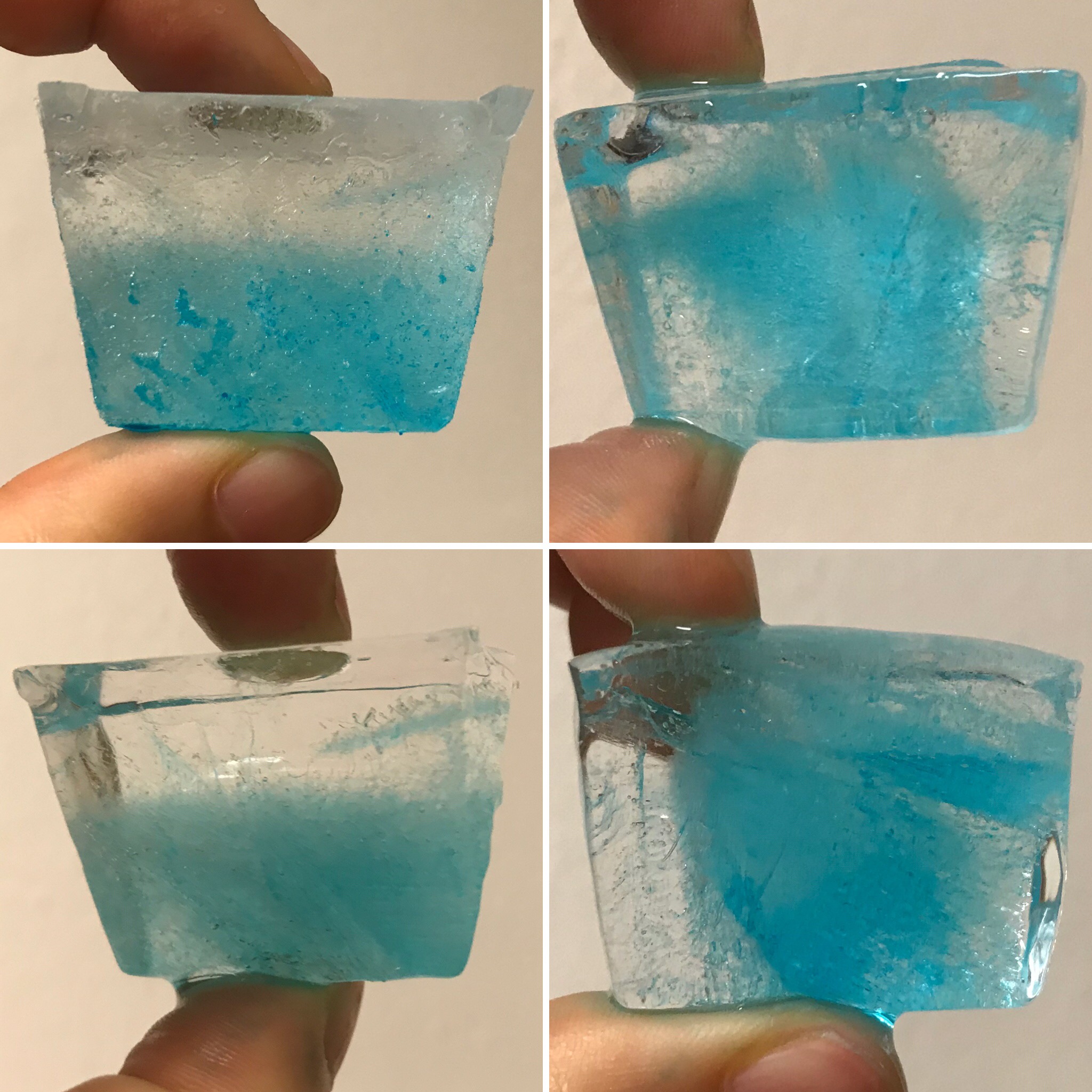

In the picture below you see something similar happening in the left pictures. Instead of salt, I have used blue food dye for visualization purposes. In the top left, you see an ice cube exactly as it looked when I took it out of the ice cube tray it froze in, and in the bottom left you see the same one after I let it melt a little bit so the surface got smoother and it got easier to look inside (a lot more difficult to hold on to, though!).

Do you see how the top part of the ice cube is pretty much clear, while the bottom part is blue? That’s because it froze top-to-bottom and the dye got pushed down during the initial freezing process!

Stuck in an ice cube tray

Something else that you see in the top left picture is the effect of the ice cube being stuck in the ice cube tray as it froze: Pores filled with blue dye that had nowhere to escape!

Had I taken out those ice cubes earlier, when they had just frozen half way through, we would have found a clear ice layer floating on a cold, blue ocean. Maybe I should do that next time!

Checking on the temperature distribution of your freezer

Something else fun we can observe from the right pictures: Here, the dye was concentrated towards the center of the ice cube rather than the bottom! How did that happen?

My theory is that those ice cubes were located in an area of the freezer that was cooling from all sides (more or less) equally, whereas the ones shown on the left must have been placed somewhere where cooling happened mainly from the top.

So if you ever want to know where the cooling in your freezer happens, just put lots of dyed little water containers everywhere and check from which side the dye gets rejected — that’s the cooling side! Actually, I might check that for the freezer below just for fun. Would you be interested in seeing that done?

Now it’s your turn!

Let’s look back at the ice cubes I froze yesterday in the picture above. I’ve now written about a lot of things I see when I look at them. What else do you see? Do you think it’s interesting to use with kids, for example? I’ve used those experiments with first year university students, too, I think there is plenty to observe and explain here!