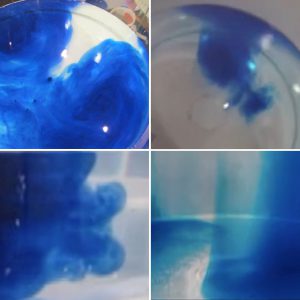

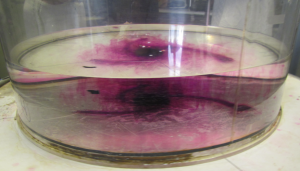

Artikel “Praxisnähe dank digitaler Versuchsküche” von P. Mertsching über remote #KitchenOceanography

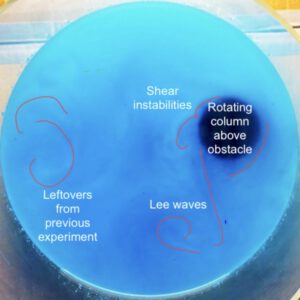

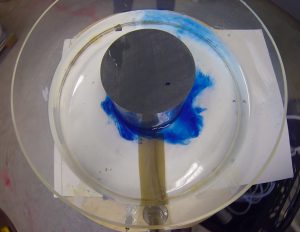

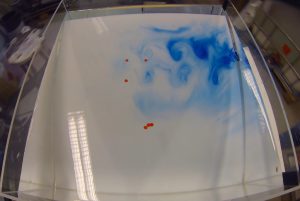

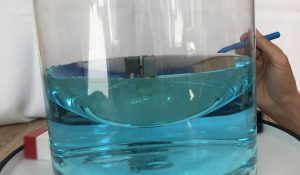

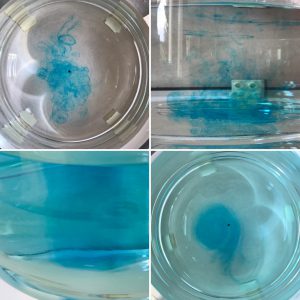

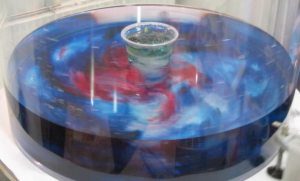

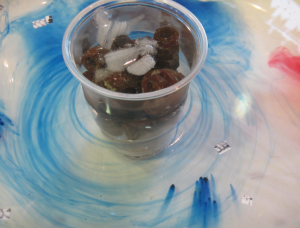

Im “eMagazin für aktuelle Themen der Hochschuldidaktik” der Uni Kiel ist der Artikel “Praxisnähe dank digitaler Versuchsküche” von Phil Mertsching über Torge’s und mein Projekt “Dry Theory 2 Juicy Reality”, insbesondere…