On October 21. and 22., I attended the fourth iEarth GeoLearning Forum (GLF). The GLF is an opportunity for geoscience teachers and students from all over Norway to meet up and learn from and with each other. This year, the GLF was organised in a hotel close to Oslo, and attended by more than 100 participants, more than 40 of those students.

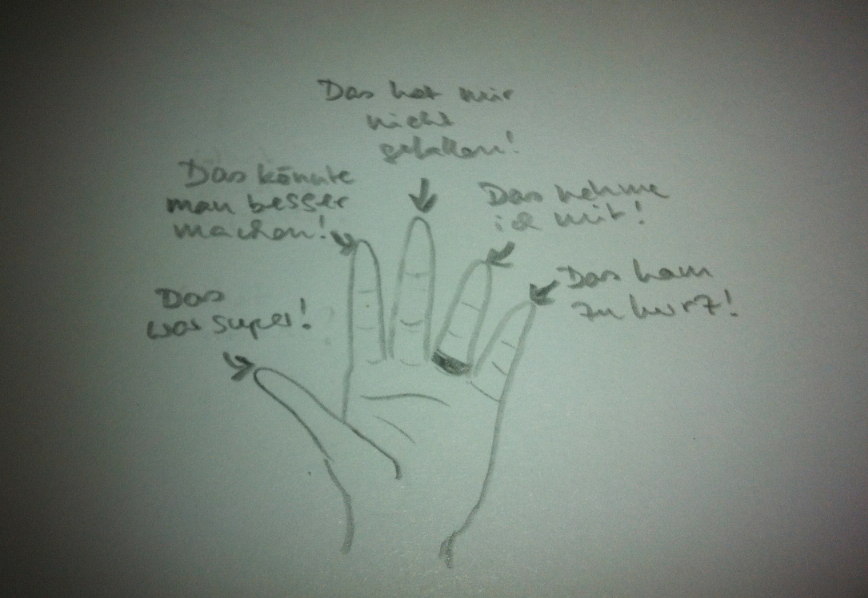

Here are a couple of reflections on the GLF, in my favourite continue, start, stop format:

Continue for GLF 2022

There were so many amazing aspects of GLF 2021 that we should definitely continue with! Here is a selection.

Continue inviting inspiring keynote speakers

For me, the highlight of this year’s GLF was definitely the keynote by Ilan Dehli Villanger, who spoke about an approach to communication and cooperation with students by “meeting, seeing, hearing, respecting, and liking (loving)”. This might sound weird at first, but there were so many practical tips and tricks connected to the keynote that we can implement in future communications: Meeting students in a space where we sit at an angle, so that the meeting isn’t confrontational and both parties can look straight ahead into empty space without having to purposefully avoid eye contact. Seeing not just our first impression of students, but questioning our assumptions about what the features we notice might mean, and why we are noticing them in the first place. Hearing students by actively listening and paraphrasing what they say to make sure we understand. Respecting students. And lastly loving — or at least liking (and acknowledging that loving might be too strong a word for some, at least to start out with) — students: Looking for something likeable in everybody, and interacting with the most likeable version of them we can make ourselves see.

The idea of “meet, see, hear, respect, and love” was carried throughout the rest of the GLF and frequently referred to in conversations and other workshops — a sign of the impact it had on us! And it was a great way of kicking off the conference and setting the tone. I don’t know who could possibly follow up on that next year — those are quite some shoes to fill!

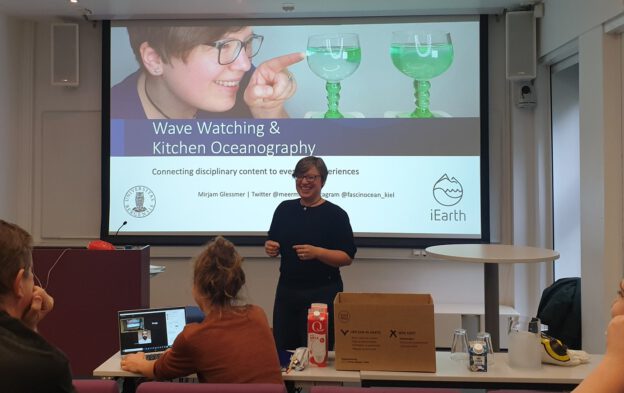

Continue mixing students and teachers, both as presenter teams and in small discussion groups

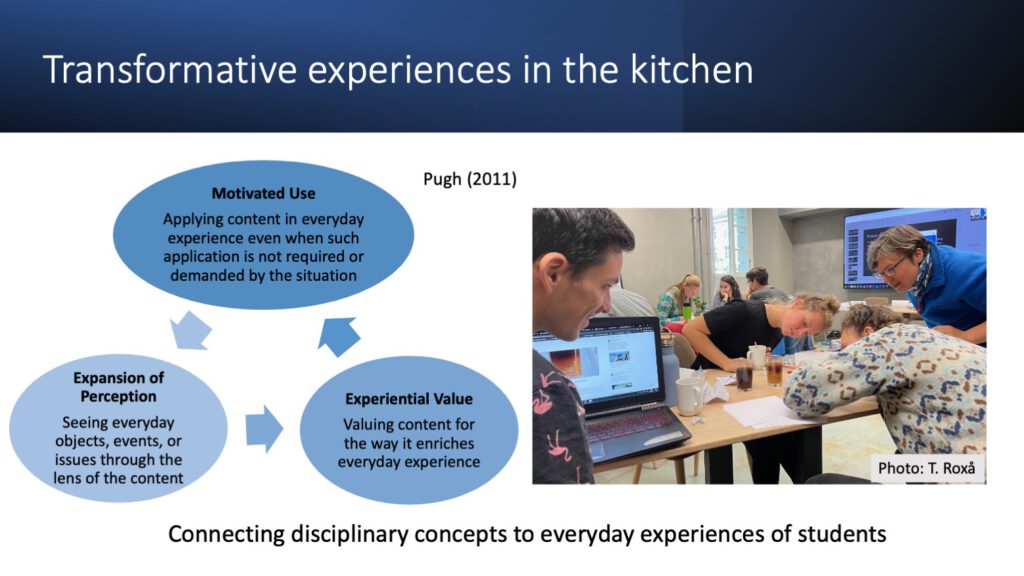

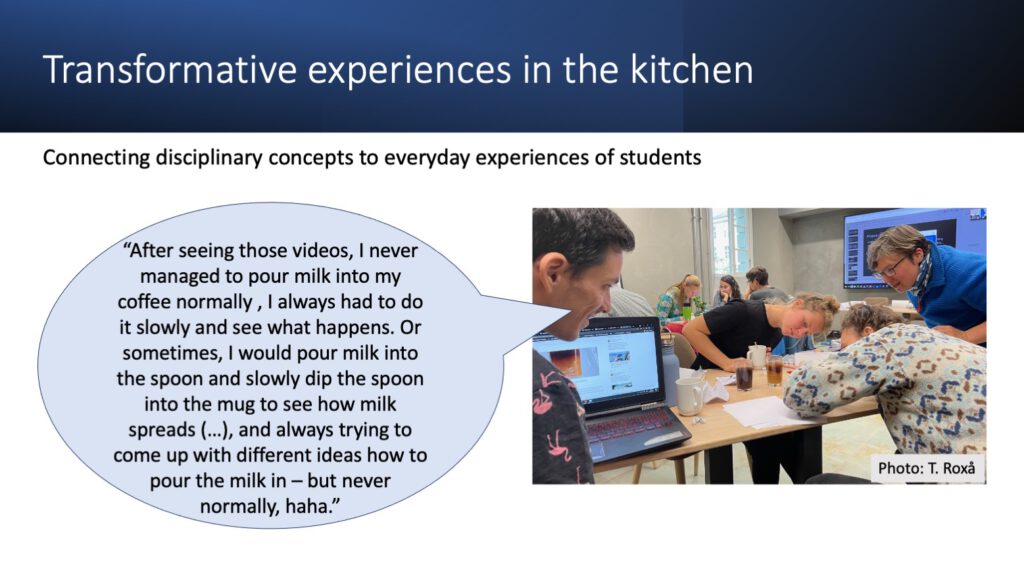

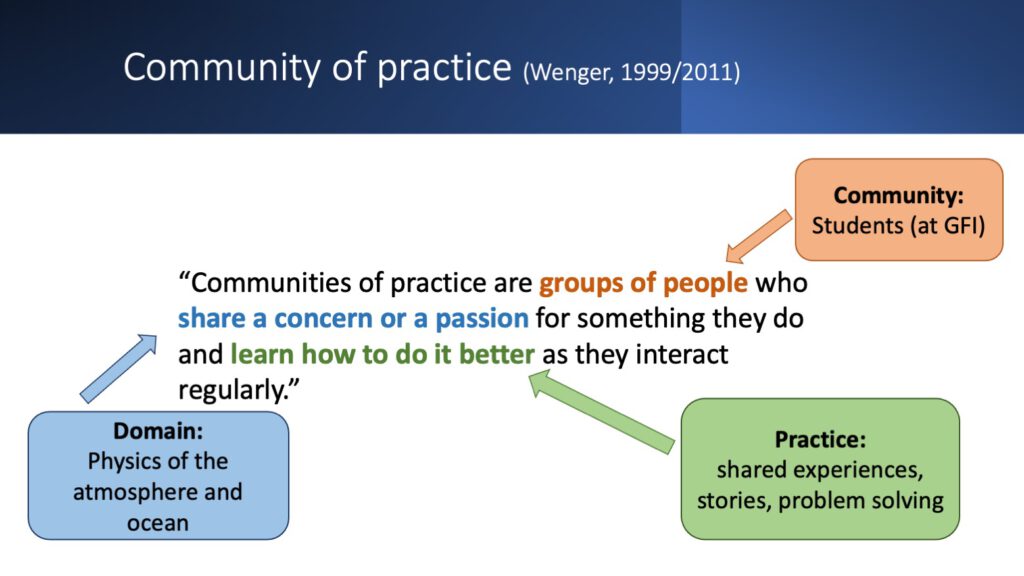

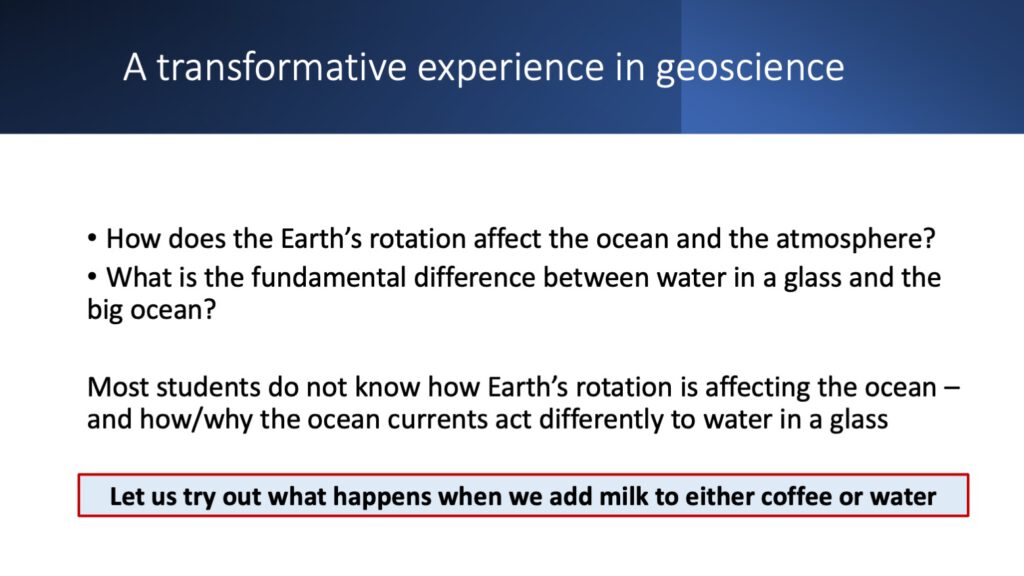

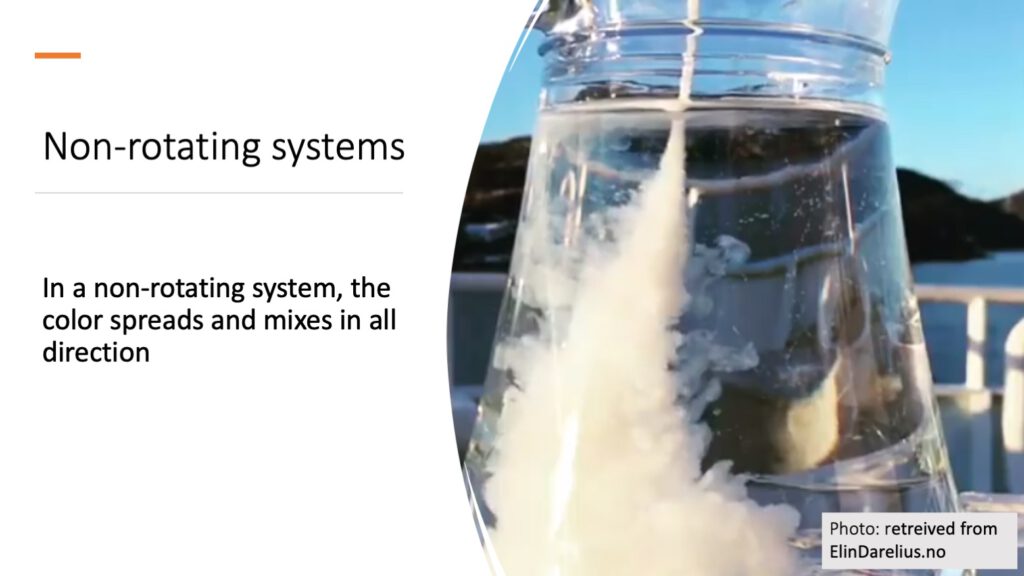

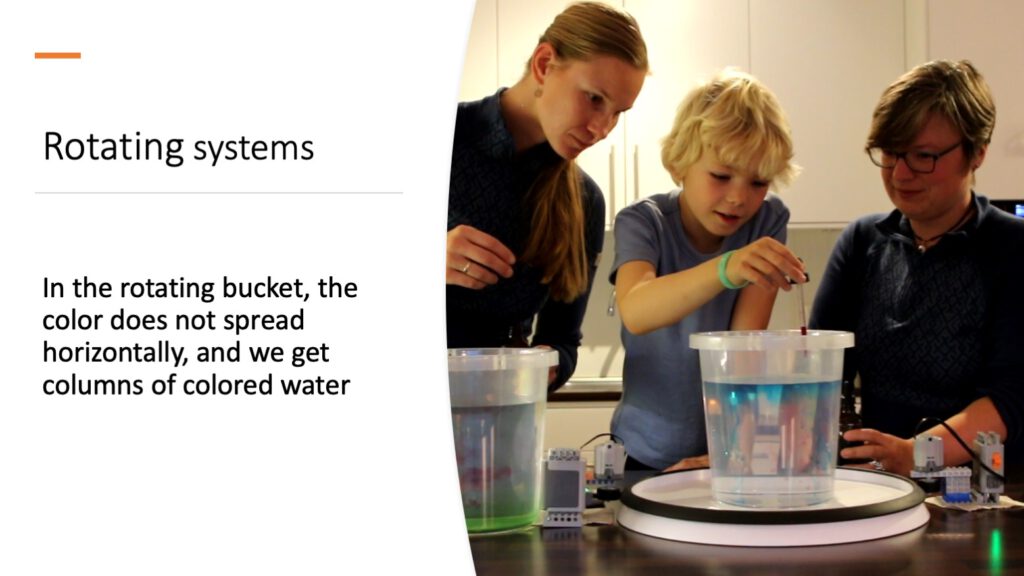

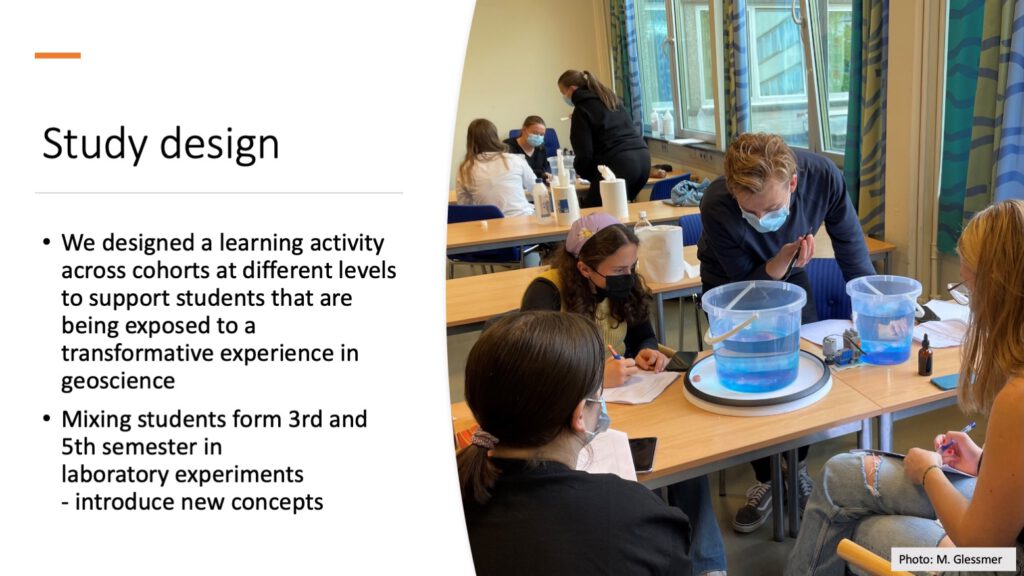

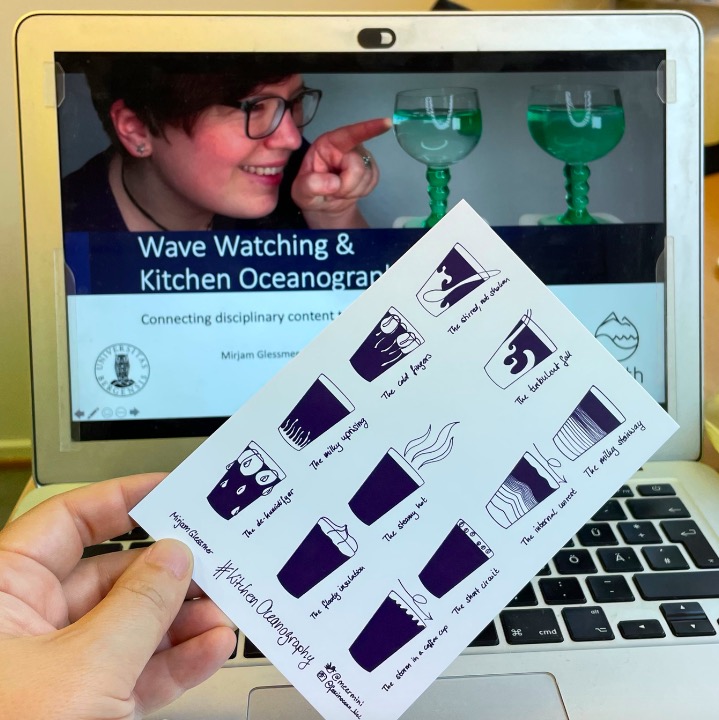

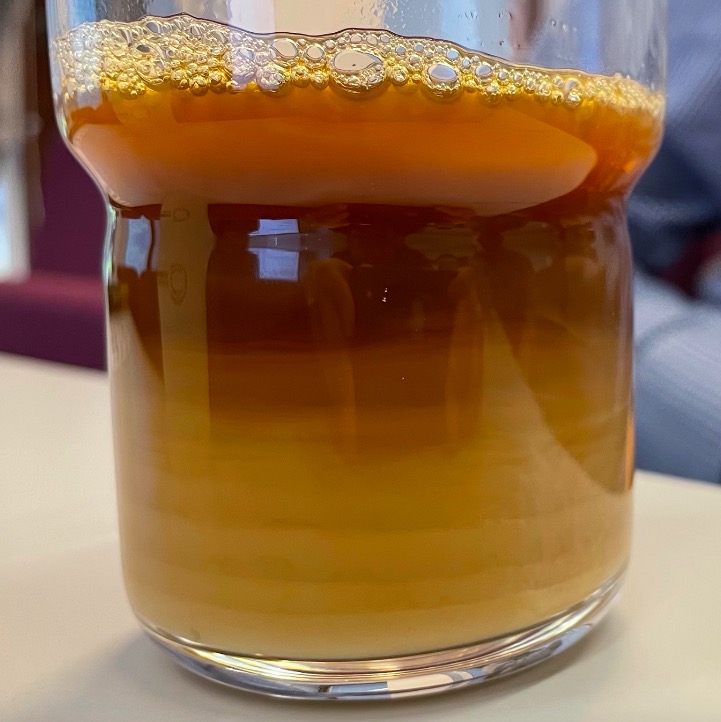

The other big highlight for me were conversations with students that I did not know beforehand, from all four iEarth universities in Oslo, Bergen, Tromsø and on Svalbard. These conversations happened in many of the workshops where teachers and students were paired in mixed groups, but also over meals and coffees, where many people made an effort to mix and talk to new people. We talked about what iEarth meant to them, how they perceived their studies, but also what iEarth means to me and what I do as part of my job. After a presentation that Kjersti Daae and myself gave on our tank experiments and a coffee break with kitchen oceanography, we also talked a lot about connecting disciplinary knowledge to everyday experiences, and how this can make studies more fun.

There were also some great student/teacher teams presenting together: Shout out to Mattias and Guro for a great team work on presenting and moderating!

Continue methods that include many diverse voices and that support transfer

I really liked how at GLF a lot of best practice was modelled: We had a “sharing session” with 3-5 minute lightening talks on different topics, a spontaneous open session where we collected topics participants would like to discuss, that were then assigned facilitators and we were just thrown into the conversations (yes, I continued talking about kitchen oceanography in coffee). At the end of the conference, we wrote a minute paper with our personal take-aways and sealed it in an envelope addressed to ourselves, and we’ll receive it mailed to us in a couple of weeks.

I also really liked the efforts to make the meeting inclusive and welcoming, e.g color-coding lanyards depending on whether people would be ok being photographed, and using microphones throughout to make sure everybody could hear.

Continue making room for fun!

This GLF, we got prizes for the coolest things: The best experiment (which was also the only experiment — but thank you anyway, Kjersti and I feel very honored :-)), and then lots of things that came out of the online form people used to sign up for the conference: The first person to sign up, the last person to sign up, the fastest sign-up, the slowest sign-up, … I had no idea all this data was being stored, but it was very nicely presented and great fun!

Start for GLF 2022

Anything we could start to make GLF 2022 even better than GLF 2021?

Start enquiring about what people want to talk about, and use that to plan the program

One conversation I had with other teachers and students about planning next year’s GLF was about whether we should have fewer sessions, so each would have just a little more time to go in a little more depth in discussions, or whether we should keep the sessions short-ish, in order to cover more different topics. My subjective take on that is that as much as I would love more in-depth discussions, we should keep the diversity — if there had only been four sessions in the whole GLF, I would have been much more likely to look at each session and think about whether each one of them would make the travel and time commitment worthwhile. Whereas now, there was such a broad program that I didn’t look through it in detail but decided to attend, trusting that there would be enough interesting pieces. So I think if we want many people to attend, we need to keep a diverse program with bits and pieces for everybody.

But I think this is a conversation that could be had in advance next time, and more generally also what the topics are that people are really interested in, both on conference level and on the level of individual workshops. Discussions on what topics would make it worthwhile to take two days out of our busy lives to attend GLF? And how can we make sure each workshop is relevant? In the workshop on “improving supervision of Master students”, for example, I was paired up with three Bachelor students. Since they had no direct experience of being a Master student, I could tell them about how I advise Master students (which might have been interesting to hear about, or not), but I felt that the topic wasn’t really the most relevant for either of us. How much better would it have been if the questions we discussed had actually been crowd-sourced in advance? Even if the questions had ended up the same, I feel like willingness to discuss them would have been higher if they had been introduced as something that either students or teachers (or possibly both) really cared about.

Start “quality control”

I’m specifically thinking of one workshop that I think was not well thought out and where the role distribution really pissed me off (think man doing all the talking, young woman being introduced as the assistant and clicking the slides forward), but in general I think it would really strengthen the GLF if there was some type of quality control implemented beforehand to make sure the workshops really serve as best practice examples. Maybe people who want to speak/present/run a workshop should write an abstract beforehand and from that pool, only some get picked? Maybe the workshop concept should be talked through with a student-teacher pair whose job it is to provide helpful feedback? Or two workshop lead teams could be paired up to provide peer-feedback? This would have the added benefit of creating connections between different sessions.

And the technology needs to be tested in advance, that was a recurring theme.

Start creating artefacts

Make contributing to GLF count — by publishing abstracts of presentations and workshops, by giving written acknowledgement on nice paper with the university seal to student contributions, by having the official role as “peer-reviewer for the improvement of workshops” that students can put on their CVs. Maybe we could also award prices for the most entertaining moderation of a workshop, the most well-designed slide, the most cited phrase (this time definitely “meet, see, hear, respect, and love”), the best interaction between workshop lead and participants?

Also I want to do a GLF bingo with all the typical things like innovation, students as partners, culture change, assessment :-D

Start making it easier to find people

For this year’s GLF, the plan was to take pictures of people as they arrived at the conference venue, and have them be projected to the big screen (together with their name, affiliation and an ice breaker like their nerd topic) during breaks to make it easier to find specific people one might want to talk to. This didn’t work out in the end, but maybe next time we could collect all this information right from the start through the form where people sign up for the GLF.

Start thinking about evaluation early on

Mattias and Guro did an evaluation this year, but if we want to improve the GLF longterm, we should set measurable goals and then try to measure whether we reached them. Maybe in terms of numbers of participants, or discussions with different people, or different discussion topics, or fit between interests and what actually happened, or … Maybe this was done this year, too, but if so I’m not aware of it.

Stop for GLF 2022

What should we stop for GLF 2022? The only thing that I can think of that I would stop is planning the meeting in a different week and across the country from other iEarth meetings, that many of the same people would attend. But the devil is in the details, and I’m not sure those kinds of things can be completely avoided, even if it would have saved us some travel…

Thank you Mattias, Thea, Kristian, and everybody else, for a truly inspiring conference!