Roxå et al. (2025): “Entangled in context: addressing academic development and choice architecture”

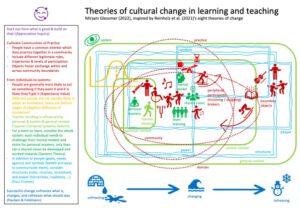

My colleague Torgny Roxå had a new paper come out (on our shared Birthday no less!) on how academic development depends on context. Together with colleagues from Bratislava, they investigate…