Thinking about theories of change (based on Reinholz et al., 2021)

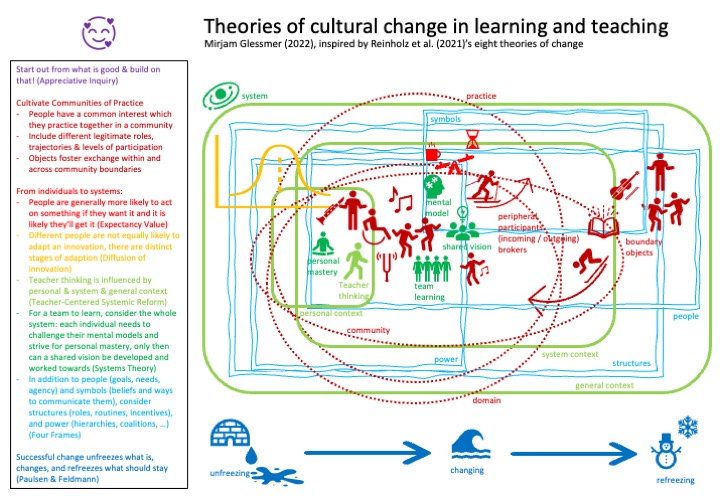

I’ve spent quite some time thinking about how to apply theories of change to changing learning and teaching culture (initially in the framework of the iEarth/BioCEED course on “leading educational change”, but more and more beyond that, too). Kezar & Holcombe (2019) say we should use several theories of change simultaneously to make things happen, and Reinholz et al. (2021), describe the eight theories of change that are most commonly used in STEM, so the most pragmatic approach for me was to consider those eight. As I’ve been discussing and applying those theories of change in practice, my thinking about them has developed a bit, and so this is how they work in my head for now (also see figure above and below; it’s the same one).

As a general mindset, it is helpful to start out from what is good already (or at least kinda working) and use that to build upon, rather than tearing everything down and starting from scratch: This is the “Appreciative Inquiry” approach in a nutshell, and it makes sense intuitively, especially when the change isn’t coming from within (for myself, I kinda like the “forget everything and start from scratch” approach) but in the form of a boss, or an academic developer, or a teacher. This appreciative inquiry approach should be considered in the planning phase of any change, but also as a general principle throughout, so we keep building on what’s positive.

“Communities of Practice” is the framework feels most natural to me, and about which I’ve read the most, so this is how I naturally think about culture and changing culture. In a community of practice, people have a common interest which they practice together in a community. The community includes different legitimate roles: not everybody needs to participate and contribute equally or in the same way, or even be fully part of the community to be accepted and appreciate (see figure above/below). There are also legitimate trajectories, i.e. ways to increase or decrease involvement as new people enter or other people leave (see the people skiing into and out of the community in the figure). Objects foster exchange within (tuning fork in the figure) and across (book and violin in the figure) community boundaries, because they are manifestations of thoughts and practice that can be transferred, re-negotiated and modified according to whatever is needed.

Communities of practice have different stages from when they first form until they eventually die, and there are design principles that can help when cultivating communtities of practice, for example to make sure participation is voluntary, there is opportunity for dialogue within and across the communities’ boundaries, and the community is nurtured by someone facilitating regular interactions and new input. In this way, I think of communities of practice as a way to co-create learning and teaching situations, making sure everybody can play the role they would like to play — be who they want to become — and take on as much ownership of the community and the change as they want.

Other theories of change address different aspects that I want to integrate in and add to my thinking about communities of practice:

- What is it that motivates individuals to do things in the first place? Generally, people are more likely to act on something if they want it and it is likely they’ll get it (-> Expectancy Value). This is depicted in the figure above/below as the considerations one might have before joining a meeting: How much time will I spend there, and is that time commitment worth the outcome I expect? All other things being the same, coffee might make it more appealing to go.

- No matter how good an idea is, people are not equally likely to jump on an innovation right away. There are distinct stages of adaption, and different “types” of people are likely to adapt in different stages: Knowing about great new ideas does not make everybody want to try them out, so just letting people know is not going to convince everybody; many people might have to see successful ideas implemented by many others before they even consider them for themselves. (-> Diffusion of innovation)

- Teacher thinking about change related to what & how to teach, who to teach and teach with, and education in general, is influenced by different contexts. These contexts include the personal context (demographics, nature & extent of preparation to teach, types & length of teaching experience, types and length of continued learning, subject & general), system context (rules and regulations, traditions, expectations, schedules, available funding and materials, physical space, subject area), and the general context. (-> Teacher-Centered Systemic Reform)

- For a team to learn, the whole system needs to be considered: each individual needs to challenge their prejudices, assumptions, and mental models; and strive for personal growth and mastery, only then can a shared vision be developed and worked towards by a whole team. (-> Systems Theory)

- In addition to people (goals, needs, agency) and symbols (beliefs and ways to communicate them) similarly to what is described above, it is often helpful to consider structures (roles, routines, incentives), and power distribution (hierarchies, coalitions, …) (-> Four Frames)

Lastly, there are three stages a person or community must go through in order to change successfully: “unfreezing” in order to create motivation for change (e.g. by realising dissatisfaction, and by feeling relatively certain that change is possible), “changing” (cognitively redefining based on feedback), and “refreezing” (making sure that the new normal is congruent with how the person wants to see themself and with the community) what should stay. (-> Paulsen & Feldmann)

And here is all of that in one figure! And maybe this figure is not so useful as a boundary object to share ideas from my brain to yours, but at least it really helped me structuring my thinking, and I am more than happy to discuss!

Kezar, A., & Holcombe, E. (2019). Leveraging Multiple Theories of Change to Promote Reform: An Examination of the AAU STEM Initiative. Educational Policy. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/0895904819843594

Reinholz, D., White, I., & Andrews, T. (2021). Change theory in STEM higher education: a systematic review. International Journal of STEM Education, 8(37), 1 – 22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-021-00291-2

Reinholz et al. (2021)'s eight most used theories of change and how they relate to each other in my head - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] been playing with this figure (inspired by the Reinholz et al. 2021 article) for a while now for the iEarth/BioCeed Leading […]

Reading about team-based faculty development (Bolander Laksov et al., 2022) - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] change isn’t an isolated event as assumed in some theories of change (for example when we unfreeze-change-refreeze), but an ever ongoing and dynamic process with, in fact, many different changes starting and ending […]