Somehow a print of the “Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice” (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006) article ended up on my desk. I don’t know who wanted me to read it, but I am glad I did! See my summary below.

Tag Archives: literature

Currently reading: JUTLP special issue on belonging in an anxious world (articles 1-7)

In response to my blog post about belonging, I was made aware of the current issue of the Journal of University Teaching and Learning Practice (JUTLP) on “Pedagogies of belonging in an anxious world“. So now I am determined to actually read that whole issue! My short summaries of the first 7 articles below.

Students’ sense of belonging, and what we can do about it

Last week, Sarah Hammarlund (of “Context Matters: How an Ecological-Belonging Intervention Can Reduce Inequities in STEM” by Hammarlund et al., 2022) gave a presentation here at LTH as part of a visit funded by iEarth* that led to a lot of good discussions amongst our colleagues about what we can do to increase students’ sense of belonging, and to the question “what can we, as teachers, do, to help students feel that they belong?”.

Below, I’m throwing together some ideas on the matter, from all kinds of different sources.

Currently reading: “Bringing an entrepreneurial focus to sustainability education: A teaching framework based on content analysis” (Hermann & Bossle, 2019)

A lot of the work I am doing at LTH is related in one way or other to teaching (how to teach) sustainability, so here are my notes on an article I recently read and found interesting:

“Bringing an entrepreneurial focus to sustainability education: A teaching framework based on content analysis” (Hermann & Bossle, 2019)

Current reading: “Syllabus Language, Teaching Style, and Instructor Self-Perception: Toward Congruence” by Richmann, Kurinec & Millsap (2020)

Yes!! People are actually responding to my “send me an article that is currently inspiring you!” request! In a comment to my blog post “Summaries of two more inspiring articles recommended by my colleagues: On educational assessment (Hager & Butler, 1996) and on variables associated with achievement in higher ed (Schneider & Preckel, 2017)“, Peggy sent me the article “Syllabus Language, Teaching Style, and Instructor Self-Perception: Toward Congruence” by Richmann, Kurinec & Millsap (2020) I am discussing below.

The Curious Construct of Active Learning: A guest post by K. Dunnett (UiO) on Lombardi et al. (2021)

‘Active Learning’ is frequently used in relation to university teaching, especially in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subjects where expository lecturing is still a common means of instruction, especially in theoretical courses. However, many different activities and types of activities can be assigned this label. This review article examines the educational research and development literature in 7 subject areas (Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, Engineering, Geography, Geosciences and Physics) to explore exactly what is meant by ‘active learning’, its core principles and defining characteristics.

Active Learning is often presented or described as a means of increasing student engagement in a teaching situation. ‘Student engagement’ is another poorly defined term, but is usually taken to involve four aspects: social-behavioural (participation in sessions and interactions with other students); cognitive (reflective thought); emotional and agentic (taking responsibility). In this way, ‘Active Learning’ relates to the opportunities that students have to construct their knowledge. On the other hand, and in relation to practice, Active Learning is often presented as the antithesis of student passivity and traditional expository lecturing in which student activity is limited to taking notes. This characterisation is related the behaviour of students in a session.

Most articles and reviews reporting the positive impact of Active Learning on students’ learning don’t define what Active Learning is. Instead, most either list example activities or specify what Active Learning is not. This negative definition introduces an apparent dichotomy which is not as clear as it may initially appear. In fact, short presentations are an important element of many ‘Active Learning’ scenarios: it is the continuous linear presentation of information that is problematic. Most teaching staff promote interactivity and provide opportunities for both individual and social construction of knowledge while making relatively small changes to previously presentation-based lectures.

That said, the amount of class time in which students are interacting directly with the material does matter. One example of measurement of the use and impact of Active Learning strategies (or activities that require students to interact with the material they are learning) in relation to conceptual understanding of Light and Spectroscopy found that high learning gains occur when at least 25% of scheduled class time is spent by students on Active Learning strategies. Moreover, the quality of the activities and their delivery, and the commitment of both students and staff to their use, are also seen as potentially important elements in achieving improved learning.

In order to develop an understanding of what Active Learning actually means, groups in seven disciplinary areas reviewed the discipline-specific literature, and the perspectives were then integrated into a common definition. The research found that presentations of Active Learning in terms of either students’ construction of knowledge via engagement, or in contrast to expository lecturing were used within the disciplines, although the discipline-specific definitions varied. For example, the geosciences definition of Active Learning was:

”Active learning involves situations in which students are engaged in the knowledge-building process. Engagement is manifest in many forms, including cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and agentic, with cognitive engagement being the primary focus in effective active learning,”

while the physics definition was that:

”Active learning encompasses any mode of instruction that does not involve passive student lectures, recipe labs, and algorithmic problem solving (i.e., traditional forms of instruction in physics). It often involves students working in small groups during class to interact with peers and/or the instructor.”

The composite definition to which these contributed is that:

”Active learning is a classroom situation in which the instructor and instructional activities explicitly afford students agency for their learning. In undergraduate STEM instruction, it involves increased levels of engagement with (a) direct experiences of phenomena, (b) scientific data providing evidence about phenomena, (c) scientific models that serve as representations of phenomena, and (d) domain-specific practices that guide the scientific interpretation of observations, analysis of data, and construction and application of models.”

The authors next considered how teaching and learning situations could be understood in terms of the participants and their actions (Figure 1 of the paper). ‘Traditional, lecture-based’ delivery is modelled as a situation where the teacher has direct experience of disciplinary practices, access to data and models, and then filters these into a simplified form presented to the students. Meanwhile, in an Active Learning model students construct their knowledge of the discipline through their own interaction with the elements of the discipline: its practices, data and models. This knowledge is refined through discussion with peers and teaching staff (relative experts within the discipline), and self-reflection.

The concluding sections remark on the typical focus of Discipline Based Educational Research, and reiterate that student isolation (lack of opportunities to discuss concepts and develop understanding) and uninterrupted expository lecturing are both unhelpful to learning, but that ”there is no single instructional strategy that will work across all situations.”

The Curious Constrauct of Active Learning

D. Lombardi, T. F. Shipley and discipline teams.

Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2021, 22 (1) 8-43

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1529100620973974

Using peer feedback to improve students’ writing (Currently reading Huisman et al., 2019)

I wrote about involving students in creating assessment criteria and quality definitions for their own learning on Thursday, and today I want to think a bit about involving students also in the feedback process, based on an article by Huisman et al. (2019) on “The impact of peer feedback on university students’ academic writing: a Meta-Analysis”. In that article, the available literature on peer-feedback specifically on academic writing is brought together, and it turns out that across all studies, peer feedback does improve student writing, so this is what it might mean for our own teaching:

Peer feedback is as good as teacher feedback

Great news (actually, not so new, there are many studies showing this!): Students can give feedback to each other that is of comparable quality than what teachers give them!

Even though a teacher is likely to have more expert knowledge, which might make their feedback more credible to some students (those that have a strong trust in authorities), it also makes it more relevant to other students, and there is no systematic difference between improvement after peer feedback and feedback from teaching staff. But to alleviate fears related to the quality of peer feedback is to use peer feedback purely (or mostly) formative, whereas the teacher does the assessment themselves.

Peer feedback is good for both giver and receiver

If we as teachers “use” students to provide feedback to other students, it might seem like we are pushing part of our job on the students. But: Peer feedback improves writing both for the students giving it as well as for the ones receiving it! Giving feedback means actively engaging with the quality criteria, which might improve future own writing, and doing peer feedback actually improves future writing more than students just doing self-assessment. This might be, for example, because students, both as feedback giver and receiver, are exposed to different perspectives on and approaches towards the content. So there is actual benefit to student learning in giving peer feedback!

It doesn’t hurt to get feedback from more than one peer

Thinking about the logistics in a classroom, one question is whether students should receive feedback from one or multiple peers. Turns out, in the literature it is not (significantly) clear whether it makes a difference. But gut feeling says that getting feedback from multiple peers creates redundancies in case quality of one feedback is really low, or the feedback isn’t actually given. And since students also benefit from giving peer feedback, I see no harm in having students give feedback to multiple peers.

A combination of grading and free-text feedback is best

So what kind of feedback should students give? For students receiving peer feedback, a combination of grading/ranking and free-text comments have the maximum effect, probably because it shows how current performance relates to ideal performance, and also gives concrete advise on how to close the gap. For students giving feedback, I would speculate that a combination of both would also be the most useful, because then they need to commit to a quality assessment, give reasons for their assessment and also think about what would actually improve the piece they read.

So based on the Huisman et al. (2019) study, let’s have students do a lot of formative assessment on each other*, both rating and commenting on each other’s work! And to make it easier for the students, remember to give them good rubrics (or let them create those rubrics themselves)!

Are you using student peer feedback already? What are your experiences?

*The Huisman et al. (2019) was actually only on peer feedback on academic writing, but I’ve seen studies using peer feedback on other types of tasks with similar results, and also I don’t see why there would be other mechanisms at play when students give each other feedback on things other than their academic writing…

Bart Huisman, Nadira Saab, Paul van den Broek & Jan van Driel

(2019) The impact of formative peer feedback on higher education students’ academic writing: a Meta-Analysis, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44:6, 863-880, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2018.1545896

Three ways to think about “students as partners”

As we get started with our project #CoCreatingGFI, we are talking to more and more people about our ideas for what we want to achieve within the project (for a short summary, check out this page), which means that we are playing with different ways to frame our understanding of co-creation and students as partners (SaP).

For the latter, I just read an article by Matthews et al. (2019) that identifies three ways that SaP is commonly being written about. Reading this article was really useful, because it made me realise that I have been using aspects of all three, and now I can more purposefully choose in which way I want to frame SaP for each specific conversation I am having.

In the following, I am presenting the three different perspectives and commenting on how they relate to how I’ve been talking — and thinking — about SaP.

Imagining through Metaphors

Metaphors are figures of speech where a description is applied to something it isn’t literally applicable to, but where it might help to imagine a different (in this case, desired) state.

“Students as partners” as a metaphor evokes quite strong reactions occasionally, because it can be perceived as a complete loss of power, authority and significance by teachers; and likewise as too much work, responsibility, stress by students. We moved away from “students as partners” as a metaphor and towards “co-creation”, because when speaking about “students as partners”, we were constantly trying to explain who the students were partnering with, and what “partnership” would mean in practice. So while we were initially attracted to the metaphor and the philosophy behind it, it ended up not working well in our context.

Speaking about the “student voice”, on the other hand, is something that I’m still doing. To me, it implies what Matthews et al. (2019) describe: students powerfully and actively participating in conversations, and actually being heard. But they also warn that this metaphor can lead to structures in which power sharing becomes less likely, which I can also see: if we explicitly create opportunities to listen to students, it becomes easy to also create other situations in which there explicitly is no space for students.

Building on concepts

When grounding conversations on accepted concepts from the literature, it makes it a lot easier to argue for them and to make sure they make sense in the wider understanding in the field.

In our proposal for Co-Create GFI, we very explicitly build all our arguments on the concept of “communities of practice”. Maybe partly because I was in a very bad Wenger phase at around that time, but mostly because it gave us language and concepts to describe our goal (teachers working together in a community on a shared practice), because it gave us concrete steps for how to achieve that and what pitfalls to avoid.

Also in that proposal as well as in our educational column in oceanography, we use “student engagement” as the basis for the co-creation we are striving for. In our context, there is agreement that students should be engaged and that teachers should work to support student engagement, so starting from this common denominator is a good start into most conversations.

Another concept mentioned by Matthews et al. (2019) are “threshold concepts”, which isn’t a concept we have used in our own conversations about SaP, but which I found definitely helpful to consider when thinking about reactions towards the idea of SaP.

Matthews et al. (2019) point out that while building on concepts can be grounding and situating the way I describe above, it can also be disruptive.

Drawing on Constructs

Of the three ways of talking about SaP, this is the one we’ve used the least. Constructs are tools to help understand behaviour by basically putting a label on a drawer, such as identity, power, or gender. Looking at SaP through the lens of different constructs can help see reality in a different way and change our approach to it, or as Matthews et al. (2019) say: “revealing can lead to revisiting”.

I know it’s not the intention of the article, but I am wondering if taking on that lens just for fun might not reveal new and interesting things about our own thinking…

Kelly E. Matthews, Alison Cook-Sather, Anita Acai, Sam Lucie Dvorakova, Peter Felten, Elizabeth Marquis & Lucy Mercer-Mapstone (2019) “Toward theories of partnership praxis: an analysis of interpretive framing in literature on students as partners”. In: teaching and learning, Higher Education Research & Development, 38:2, 280-293, DOI: 10.1080/07294360.2018.1530199

Using student evaluations of teaching to actually improve teaching (based on Roxå et al., 2021)

There are a lot of problems with student evaluations of teaching, especially when they are used as a tool without reflecting on what they can and cannot be used for. Heffernan (2021) finds them to be sexist, racist, prejudiced and biased (my summary of Heffernan (2021) here). There are many more factors that influence whether or not students “like” courses, for example whether they have prior interested in the topic — Uttl et al. (2013) investigate the interest in a quantitative vs non-quantitative course at a psychology department and find a difference in interest of nearly six standard deviations! Even the weather on the day a questionnaire is submitted (Braga et al., 2014), or the “availability of cookies during course sessions” (Hessler et al., 2018) can influence student assessment of teaching. So it is not surprising that in a meta-analysis, Uttl et al. (2017) find “no significant correlations between the [student evaluations of teaching] ratings and learning” and they conclude that “institutions focused on student learning and career success may want to abandon [student evaluation of teaching] ratings as a measure of faculty’s teaching effectiveness”.

But just because student evaluations of teaching might not be a good tool for summative assessment of quality, especially when used out of context, that does not mean they can’t be a useful tool for formative purposes. Roxå et al. (2021) argue that the problem is not the data in itself, but the way it is used, and suggest using them — as academics do every day with all kinds of data — as basis for a critical discourse, as a tool to drive improvement of teaching. They suggest also changing the terminology from “student rating of teaching” to “course evaluations”, to move the focus away from pretending to be able to measure quality of teaching, towards focussing on improving teaching.

In that 2021 article, Roxå et al. present different way to think about course evaluations, supported by a case study from the Faculty of Engineering at Lund University (LTH; which is where I work now! :-)). At LTH, the credo is that “more and better conversations” will lead to better results — in the context of the Roxå et al. (2021) article meaning that more and better conversations between students and teachers will lead to better learning. “Better” conversations are deliberate, evidence-based and informed by literature.

At LTH, the backbone for those more and better conversations are standardised course evaluations run at the end of every course. The evaluations are done using a standard tool, the “course experience questionnaire”, which focusses on the elements of teaching and learning that students can evaluate: their own experiences, for example if they perceived goals as clearly defined, or if help was provided. It is LTH policy that results of those surveys cannot influence career progressions; however, a critical reflection on the results is expected, and a structured discussion format has been established to support this:

The results from those surveys are compiled into a working report that includes the statistics and any free-text comments that an independent student deemed appropriate. This report is discussed in a 30-45 min lunch meeting between the teacher, two students, and the program coordinator. Students are recruited and trained specifically for their role in those meetings by the student union.

After the meeting and informed by it, each of the three parties independently writes a response to the student ratings, including which next steps should be taken. These three responses together with the statistics then form the official report that is being shared with all students from the class.

The discourse and reflection that is kick-started with the course evaluations, structured discussions and reporting is taken further by pedagogical trainings. At LTH, 200 hours of training are required for employment or within the first 2 years, and all courses include creating a written artefact (and often this needs to be discussed with critical friends from participants’ departments before submission) with the purpose of make arguments about teaching and learning public in a scholarly report, contributing to institutional learning. LTH also rewards excellence in teaching, which is not measured by results of evaluations, but the developments that can be documented based on scholarly engagement with teaching, as evidenced for example by critical reflection of evaluation results.

At LTH, the combination of carefully choosing an instrument to measure student experiences, and then applying it, and using the data, in a deliberate manner has led to a consistent increase of student evaluations of the last decades. Of course, formative feedback happening throughout the courses pretty much all the time will also have contributed. This is something I am wondering about right now, actually: What is the influence of, say, consistently done “continue, start, stop” feedbacks as compared to the formalized surveys and discussions around them? My gut feeling is that those tiny, incremental changes will sum up over time and I am actually curious if there is a way to separate their influence to understand their impact. But that won’t happen in this blogpost, and it also doesn’t matter very much: it shouldn’t be an “either, or”, but an “and”!

What do you think? How are you using course evaluations and formative feedback?

Braga, M., Paccagnella, M., & Pellizzari, M. (2014). Evaluating students’ evaluations of professors. Economics of Education Review, 41, 71-88.

Heffernan, T. (2021). Sexism, racism, prejudice, and bias: a literature review and synthesis of research surrounding student evaluations of courses and teaching. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 1-11.

Hessler, M., Pöpping, D. M., Hollstein, H., Ohlenburg, H., Arnemann, P. H., Massoth, C., … & Wenk, M. (2018). Availability of cookies during an academic course session affects evaluation of teaching. Medical Education, 52(10), 1064-1072.

Roxå, T., Ahmad, A., Barrington, J., Van Maaren, J., & Cassidy, R. (2021). Reconceptualizing student ratings of teaching to support quality discourse on student learning: a systems perspective. Higher Education, 83(1), 35-55.

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Morin, A. (2013). The numbers tell it all: students don’t like numbers!. PloS one, 8(12), e83443.

Uttl, B., White, C. A., & Gonzalez, D. W. (2017). Meta-analysis of faculty’s teaching effectiveness: Student evaluation of teaching ratings and student learning are not related. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 54, 22-42.

Just published: Co-Creating Learning in Oceanography

Kjersti and I just had an article published: “Co-Creating Learning in Oceanography” (Glessmer & Daae, 2021)!

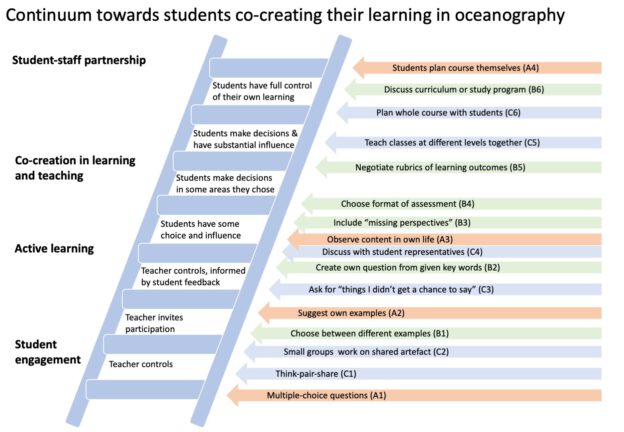

In this article, we discuss ways in which to share responsibility for learning between teachers and students on a continuum from “just” actively engaging students towards fully shared responsibility, i.e. “co-creation” or “Students as Partners”. We give 13 different examples from our own praxis, starting from very easy things like how to use multiple-choice questions to promote discussion and critical thinking or giving students the choice of several examples from which they can learn the same content, and gradually work our way up to more and more interesting methods, like for example negotiating rubrics of learning outcomes with students.

The article itself is accompanied by a website where we elaborate on our 13 different examples. Check it out, and let us know what you think! And if you have any experiences with co-creating learning that you would like to share, we would love to hear from you and add a guest post on your experiences to our collection! :)

Reference:

Glessmer, M.S., and K. Daae. 2021. Co-creating learning in oceanography. Oceanography 34(4), https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2021.405.