If you’ve been trying to actively engage students in your classes, I am sure you’ve felt at least some level of resistance. Even though we know from literature (e.g. Freeman et al., 2014) that active learning increases student performance, it’s sometimes difficult to convince students that we are asking them to do all the activities for their own good.

But I recently came across an article that I think might be really good to help convince students of the benefits of active learning: Deslauriers et al. (2019) are “measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom” in different physics classes. They compare active learning (which they base on best practices in the given subject) and passive instruction (where lectures are given by experienced instructors that have a track record of great student evaluations). Apart from that, both groups were treated equally, and students were randomly assigned to one or the other group.

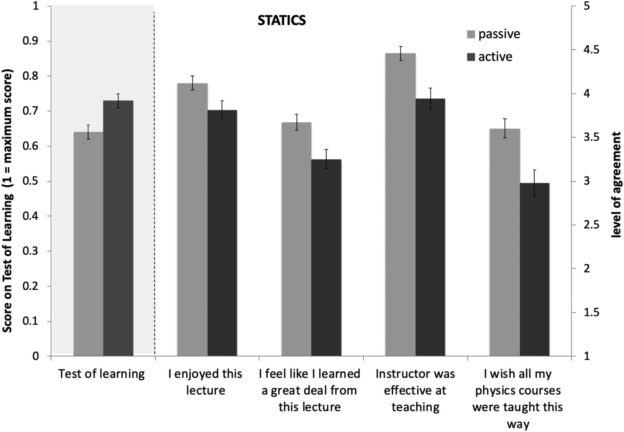

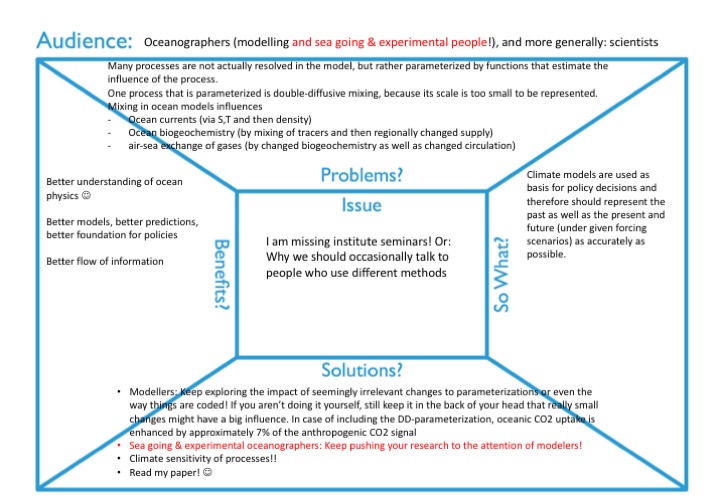

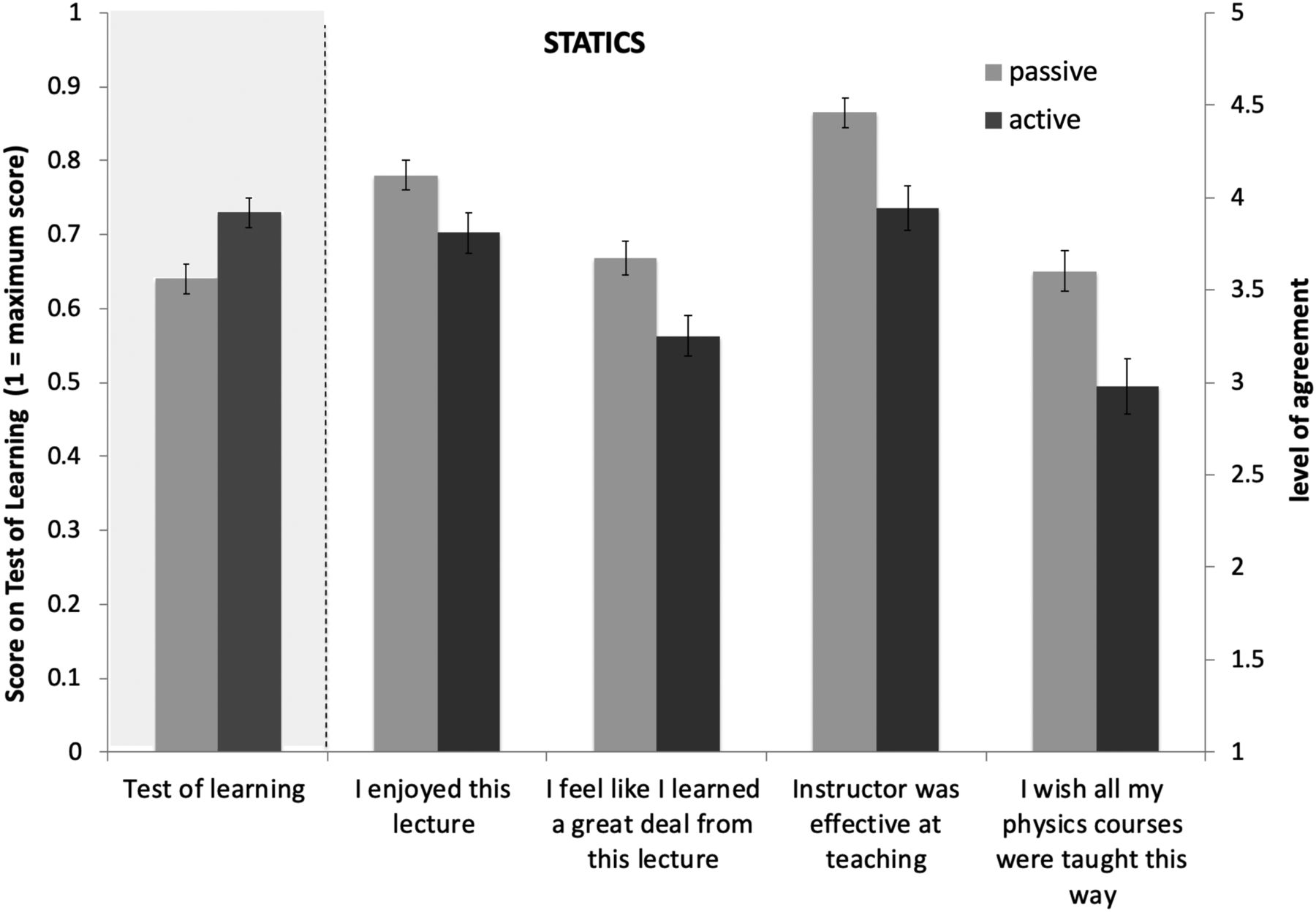

Figure from Deslauriers et al. (2019), showing a comparison of performance on the test of learning and feeling of learning responses between students taught with a traditional lecture (passive) and students taught actively for the statics class

As expected, the active case led to more learning. But interestingly, despite objectively learning more in the active case, students felt that they learned less than the students in the passive group (which is another example that confirms my conviction that student evaluations are really not a good measure of quality of instruction), and they said they would choose the passive learning case given the choice. One reason might be that students interpret the increased effort that is required in active learning as a sign that they aren’t doing as well. This might have negative effects on their motivation as well as engagement with the material.

So how can we convince students to engage in active learning despite their reluctance? Deslauriers et al. (2019) give a couple of recommendations:

- Instructors should, early on in the semester, explicitly explain the value of active learning to students, and explicitly point out that increased cognitive effort means that more learning is taking place

- Instructors should also have students take some kind of assessment early on, so students get feedback on their actual learning rather than relying only on their perception

- Throughout the semester, instructors should use research-based strategies for their teaching

- Instructors should regularly remind students to work hard and point out the value of that

- Lastly, instructors should ask for frequent student feedback throughout the course (my favourite method here) and respond to the points that come up

I think that showing students data like the one above might be really good to get them to consider that their perceived learning is actually not a good indicator for their actual learning, and convincing them that putting in the extra effort that comes with active learning is helping them learn even though it might not feel like it. I’ve always explicitly talked to students about why I am choosing certain methods, and why I might continue doing that even when they told me they didn’t like it. And I feel that that has always worked pretty well. Have you tried that? What are your experiences?

—

Measuring actual learning versus feeling of learning in response to being actively engaged in the classroom

Louis Deslauriers, Logan S. McCarty, Kelly Miller, Kristina Callaghan, Greg Kestin

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

Sep 2019, 16 (39) 19251-19257; DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1821936116