Maybe it was because of the contexts in which I encountered it, but I always perceived “co-creation” as an empty buzzword without any actionable substance to it. I have only really started seeing the huge potential and getting excited about it since I met Catherine Bovill. Cathy and I are colleagues in the Center for Excellence in Education iEarth, and I have attended two of her workshops on “students as partners” and now recently read her book (Bovill, 2020). And here are my main takeaways:

Speaking about students as partners can mean very many, very different things. The partnership between students and teachers is “a collaborative, reciprocal process through which all participants have the opportunity to contribute equally, although not necessarily in the same ways, to curricular or pedagogical conceptualizations, decision-making, implementation, investigation, or analysis” (Cook-Sather et al., 2014). For me, understanding the part about contributing equally, although not necessarily in the same ways really helped to get over objections like “but I am responsible for what goes on in my course and that students have the best possible environment for their learning. How can I put part of that responsibility on students? And can they even contribute in a meaningful way when they are not experts yet?” and the key is that they are contributing as equals, but that does not mean that we are sharing responsibility or tasks (or anything necessarily!) 50/50.

Including students as partners to co-create their learning and teaching leads to many advantages: the forms of teaching and learning that are created in such a process are more engaging to students and more human in general. Since it feels more relevant to students, learning is enhanced, and becomes more inclusive. The student also experience new roles which helps them in becoming more independent, secure, and responsible. And it seems to be a lot of fun for the teacher, too, because a lot of new opportunities for positive interactions are created.

“Students as partners” does not mean that one necessarily has to jump into the pool at the deep end and re-design the whole curriculum from scratch. There is a whole continuum of increasing student participation where a teacher only gradually shares more and more control, and every small move towards more participation is a step in the right direction. This includes many smaller steps I’ve implemented in my teaching already, without even realising that that could be counted as working towards “students as partners”!

Some of those small steps suggested in the book and that can already have a positive impact include

- Reserving one or two lessons at the end of the semester for perspectives or topics that students would like included (which I personally have really good experiences with!).

- Giving student questions back into the group with the question “what do you think? and why?”, sharing the power to answer questions rather than claiming it solely for the teacher.

- Doing a “note-taking relay”: at regular intervals, the teacher stops and gives time for students to take notes. Students do take notes and then pass them on to their neighbour. At the next note-taking break, they take notes on that piece of paper in front of them, and then pass it on to the next neighbour. They are thus creating a documentation of the class with and for each other.

- Invite students to create study guides or resources for next year’s students.

- Invite them to design infographics, slides, diagrams on important topics, or present their own role plays of different theories in fictitious situations, which then are used in teaching of their own class.

Especially this last point I think I might have underestimated until now. When I saw my name mentioned in the newsletters of my two favourite podcasts this week, it made me feel super proud! If students only feel a fraction of that pride when their work is featured in a course as something that other people can learn from, it is something we should be doing MUCH MORE!

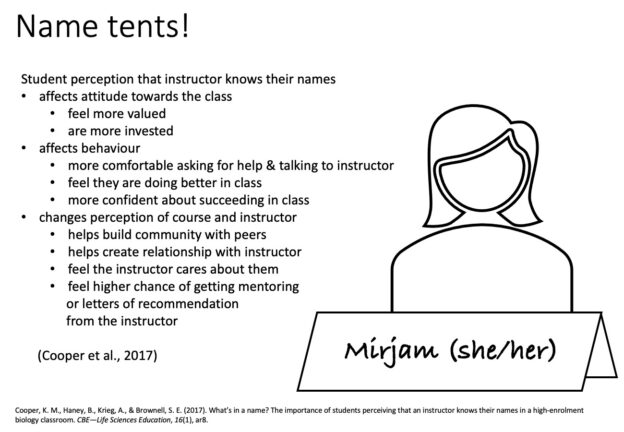

Other things that come to my mind that share responsibility in small ways or strengthen relationships:

If you (and they!) so choose, students could also become partners on bigger parts of the course, and especially on designing their own assessment, and in evaluating the class. Here are some examples described in the book:

- In one of her own courses on the topic of educational research (which probably included how to gather data in order to evaluate teaching and learning), Cathy invited students to pick aspects of her course which they wanted to evaluate, and then work with her to design an evaluation, analyse the data and present their findings.

- She also describes how she invited Master students to co-design dissertation learning outcomes, and that it was possible to include it in the official university regulations: In addition to the ones that are prescribed for all students, each student gets to design one individually in collaboration with their supervisor.

- Another idea she presents is to give students key words and let them create their own essay titles including those keywords. They have the freedom to choose what question they find most interesting related to a certain topic, while the teacher can make sure the important keywords from their point of view are included. But it is then important that students and teacher work together to make sure the scope is right and there is enough literature to answer that question!

- And it is possible to let students vote on the weighting of different assessment components towards their final grade. This could even be done with boundary conditions that, e.g., each assignment will have to count for at least a certain percentage. Apparently the outcomes of such votes do not vary much from year to year, but still it is increasing student buy-in a lot!

Or, going further along that continuum of students as partners, students can get involved in the whole process of designing, conducting, evaluating and reporting on a course.

- Cathy presents an example of a business course where student groups come up with business ideas in the beginning and then everybody discusses what students would need to learn in order to make those ideas become reality. Those topics are then presented to each other by different student groups.

- The point above reminds me of something I heard on a podcast, where the students also got involved in presenting materials and the teacher gave them the choice of which topics they wanted to present themselves and which topics they would prefer taught by the teacher. This sounds like a great idea to give the students the opportunity to pick the topics they are really interested in and at the same time leave the seemingly less attractive topics (or those where they would really value the teacher’s experience in teaching them) to the teacher.

- A project I am currently working on with Kjersti and Elin, where we bring together students that took a class the previous year with students who are taking it this year in order for them to do some tank experiments together, but working towards different learning outcomes depending on their level. Here the older students help the younger ones by engaging in dialogue with them and acting as role models, while also “learning through teaching”. We are working on engaging the students in designing the learning environment, and it is super exciting!

- In a recent iEarth Digital Learning Forum, Mattias and Guro described the process of completely re-designing a course in dialogue between the teacher and a team of students. And not only did they co-design the course, they also presented it together (which is a step that is really easy to forget when the partnership isn’t fully internalized yet!).

I really like the framework of “students as partners” as a reminder to think about including students in a different way, and especially to think about it as a continuum where it’s ok — and even encouraged! — to start small, and then gradually build on it. And I am excited about trying more radical forms of “students as partners” in the future!

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-creating learning and teaching: Towards relational pedagogy in higher education. Critical Publishing.

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C., & Felten, P. (2014). Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: A guide for faculty. John Wiley & Sons.