Currently reading Wenger et al. (2011) on “Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and networks: A conceptual framework”

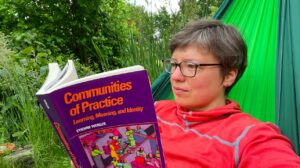

You might associate the name “Wenger” with Communities of Practice, as do I. So then it’s very interesting to read Wenger et al. (2011), where they distinguish between a community…