For many people it has been (and still is!) a huge hassle to quickly figure out ways to teach field courses in a covid-19 world, and I can relate so much! But I’m also getting more and more excited about the possibilities that are opening up when we think about fieldwork in a new way. And as I’ve been researching and teaching workshops for university teaching staff on how to transition field courses into a socially-distanced world, I have seen many exciting examples. In this blogpost, I want to share what I think is important to consider when transitioning field courses online, and some really amazing ways I’ve seen it done in the second half of the post.

Most importantly: Don’t despair, and don’t undermine whatever you end up doing!

Yes, we’d all prefer to be outside for our field courses, and not stuck to our home office, looking at our students’ faces in tiny moving stamps on a video call (at best) or talking into the wide, quiet void (at worst). There are many ways to bring fieldwork to life even in socially-distant settings, and even small “interventions” might have a large effect.

There are a couple of things we need to keep in mind:

Students might actually learn better in an unconventional setting

While we like to think that field courses are taught a certain way because they have been optimized for the specific learning outcomes, that might not actually always be the case. In many cases, they are just following a tradition without actually questioning it (and I’ll talk a little about why that is bad further down). And there are studies that show that sometimes virtual learning environments work better than traditional ones: Finkelstein (2005) showed for a direct current circuit laboratory that students who used simulated equipment outperformed students who went through a conventional lab course, both on a conceptual survey of the domain and in the coordinated tasks of assembling a real circuit and describing how it worked. So why would we assume that similar things might also be true for virtual field courses?

Virtual science is real science, too

Honestly, how many scientists do we know who are in the field every day or even only most of the time? Very very few. Most science these days happens virtually, whether data is acquired remotely, or whether scientists are using datasets that other people measured, or scientists working with numerical models. Virtual science is real science, too, and therefore even though it is not the only kind of science, maybe it’s helpful to convey to the students that while they are missing out on a fun experience (and certainly on some learning outcomes that we wish they had), they are still able to do real science.

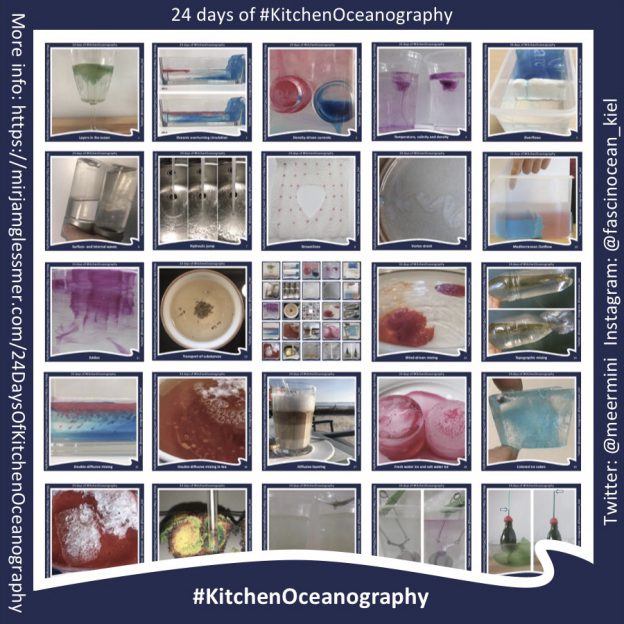

(On that note: Kitchen Oceanography is also science! Check out this post for proof…)

Don’t accidentally undermine your virtual field work

That said, while I think it’s important to be honest about what is lost — the travel to an exciting destination, the experience of being on a research ship, the smell of a certain weather pattern, the feeling of different temperatures and humidities than at home — we need to be super careful to not undermine whatever we end up teaching virtually. It’s maybe not our first choice to do it this way, and we might not have spent as much time preparing it as we would have liked, but constantly telling students what they are missing out on is not going to increase their motivation in a time that is already taxing on everybody.

What are field courses?

When I’m speaking about field courses here, what I envision are the kind of field courses I am familiar with in STEM education: Excursions where biologists investigate an ecosystem, sea practicals where oceanographer spend time on a research ship, trips where engineering students look at structures for coastal protection in situ — basically outdoor teaching.

Following the classification by Fedesco et al. (2020), those would all either fall into the categories of

- “collecting primary data/visiting primary sources”, where students enter an authentic, new-to-them research setting in order to do open-ended investigations on data that they generate while in the field, and where learning outcomes (partly — I would argue that many learning outcomes don’t) depend on the results of that data. Students are creating new knowledge and are actively participating in authentic research processes;

- “guided discovery of a site”, where the instructor is familiar with the site and plans activities that help students discover things, leading to pre-defined learning outcomes, because students are working with skills and concepts that they learned earlier in the course and apply them to a setting that is known in advance; or maybe

- “backstage access”, where students visit a site that people usually don’t have access to, for example a wave power plant (or, when I was teaching the intro to oceanography a looong time ago back in Bergen, a company that makes oceanographic instrumentation, thanks Ailin!).

Learning outcomes in field courses

While field courses might have very specific, subject- and location-specific content, there are many learning outcomes that are common to most field courses, e.g.

- social development

- observation and perception skills

- giving meaning to learning

- providing first-hand experience

- stimulating interest and motivation

(Compare Larsen et al., 2017, and others)

I think it is super helpful (always, but especially in this case) to look closely at learning outcomes, and to see how interconnected they really are. When I did this for the courses I am currently involved in, it turned out that surprisingly many of the learning outcomes can very easily be done virtually. Anything that is to do with planning of experiments, data analysis, learning of concepts could be disconnected from practicing observational skills or team working. And once they are disconnected, they can be practiced in different exercises which don’t have to rely on the same method of instruction. This makes it much easier to, for example, practice some parts in online discussions, while other parts required students to be outside and observe something themselves. The more things become modular in your mind, the easier it is to implement them.

What motivates students in field courses

When we think about field courses, we usually remember (and envision) them as extremely motivating because typically they are the occasions where students get super excited and want to dig deep and really understand the material. But why is that?

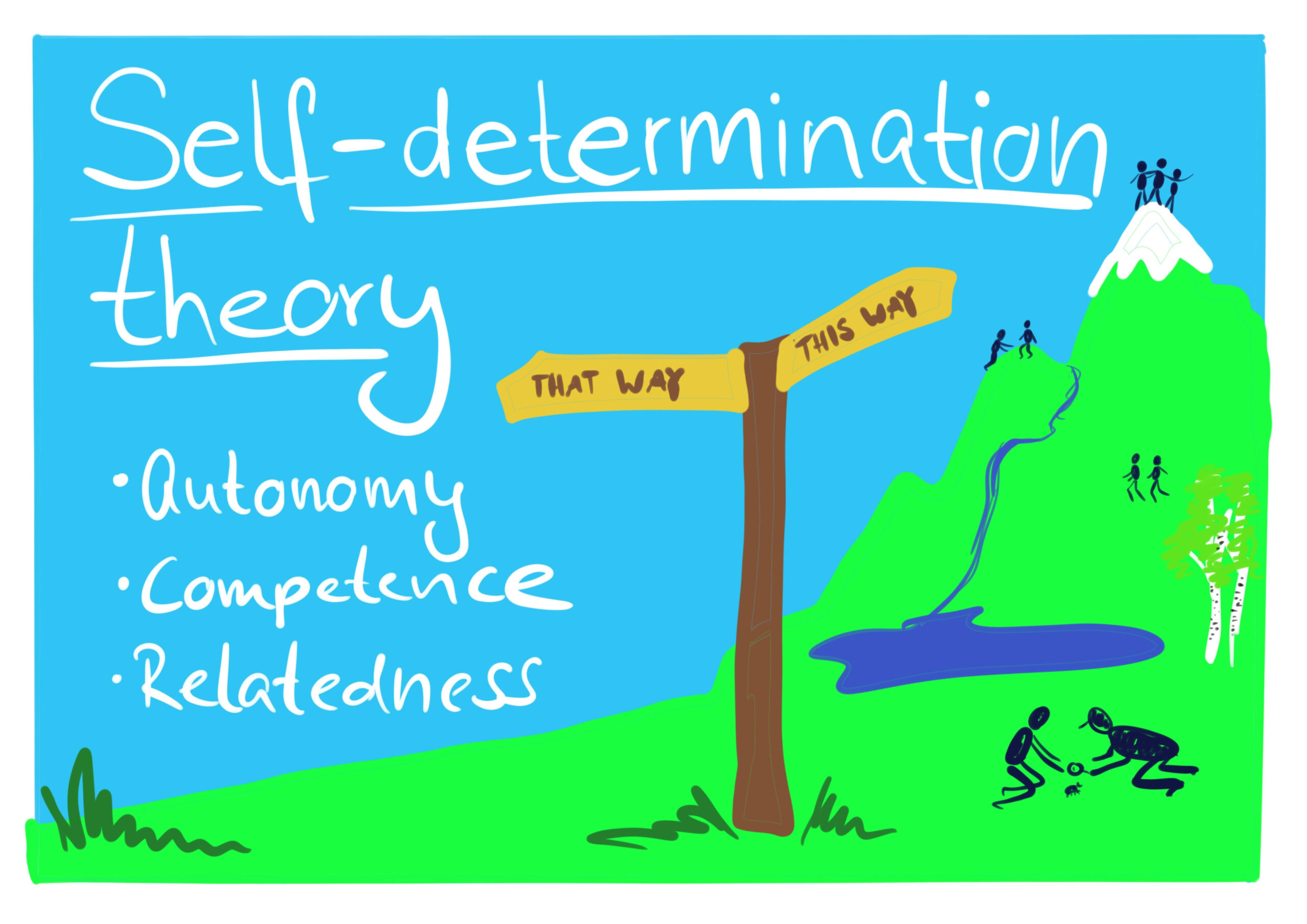

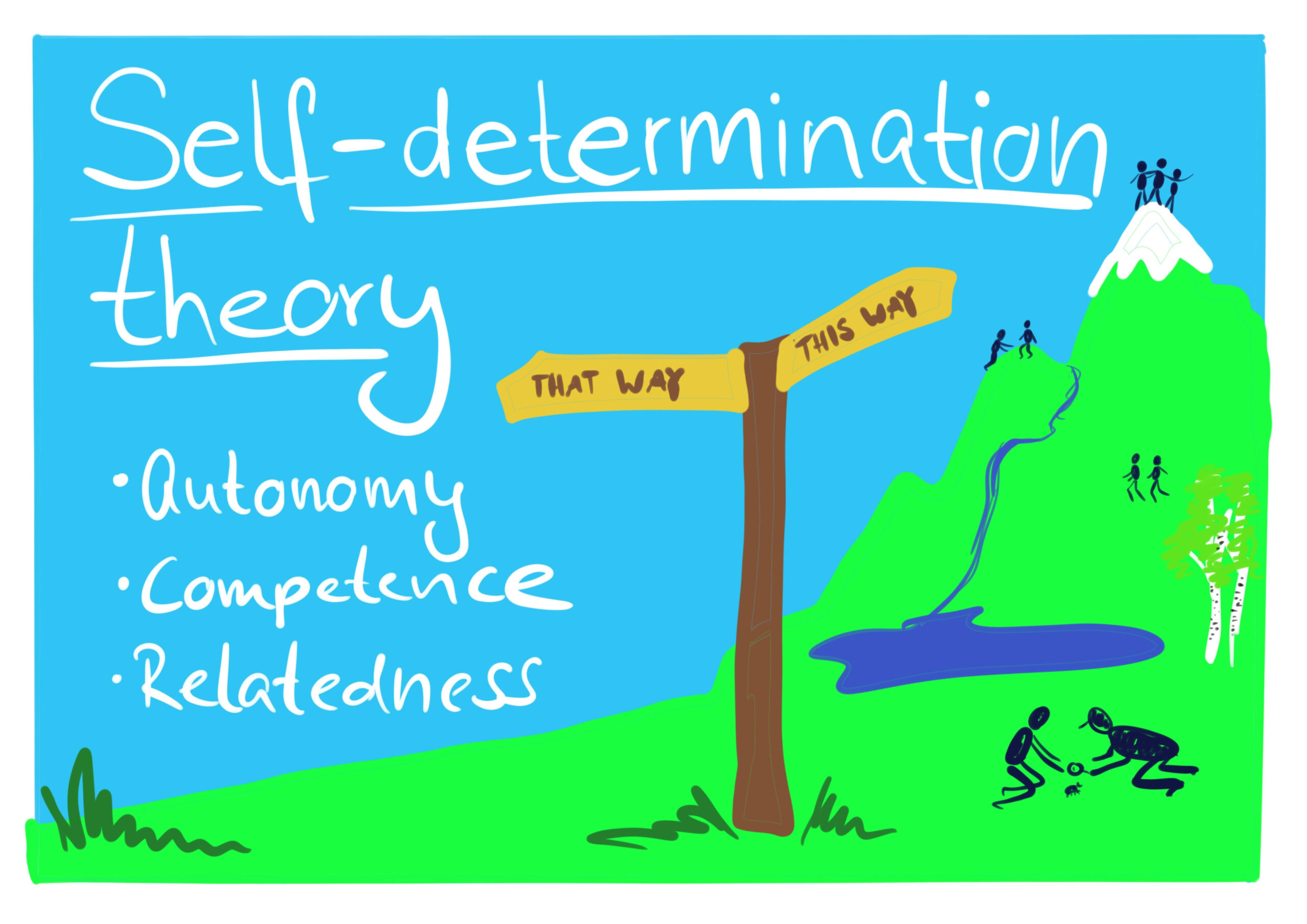

One explanation can be found in the self-determination theory by Deci & Ryan, where three basic psychological needs that need to be fulfilled in order for people to feel instrinsic motivation are described: autonomy, competence and relatedness.

Autonomy in the context of a field course means that students typically get to decide more when they are out and about doing fieldwork than when they are passively sitting in a lecture, just consuming whatever someone else decided to talk about. They might or might not get to decide what kind of questions they work on, but even if they don’t they are a lot more free in how they structure their work, how they interact with peers during that time, …

Interacting with peers is an important component for the second basic psychological need: Relatedness. In field courses, students and instructors typically spend informal time together: sitting in a bus, waiting for a boat, during the actual fieldwork. This provides opportunities for conversations that might otherwise not happen, to relate to peers and instructors on a more personal level, to also experience instructors as role models.

Lastly, field courses help students feel competence in a way they usually don’t get to in normal university settings. They work long days, potentially under challenging physical conditions, on the kind of question that they feel is more authentic than the exercises they typically do. So this might be one of the few times where they feel competent in the identity they are trying to develop: as a professional in their chosen field.

Barriers to fieldwork

But all the benefits of fieldwork come at a price (Giles et al., 2020). And those costs are not to be underestimated, especially because the barriers to fieldwork are especially felt by disabled students and those from racial and ethnic minorities, all of whom are critically underrepresented in the geosciences anyway.

Barriers include for example

- the financial burden of travel / equipment / functional clothing

- the emotional burden of dealing with daunting practical aspects of being outdoors (toilet breaks, periods)

- the physical burden of accessibility issues (the physically challenging aspects of fieldwork that are satisfying and fun for some can on the other hand completely exclude others)

- the logistical and financial burden (and emotional!) of finding a replacement for caring responsibilities

- the mental burden of dealing with previous or expected harassment and inappropriate behavior

In the light of all these burdens, there is an urgent need to consider what can be done to make traditional field courses more accessible! And I think having to reinvent so many things now is a great opportunity to make sure those barriers are taken down.

Things to consider when filming for virtual field courses

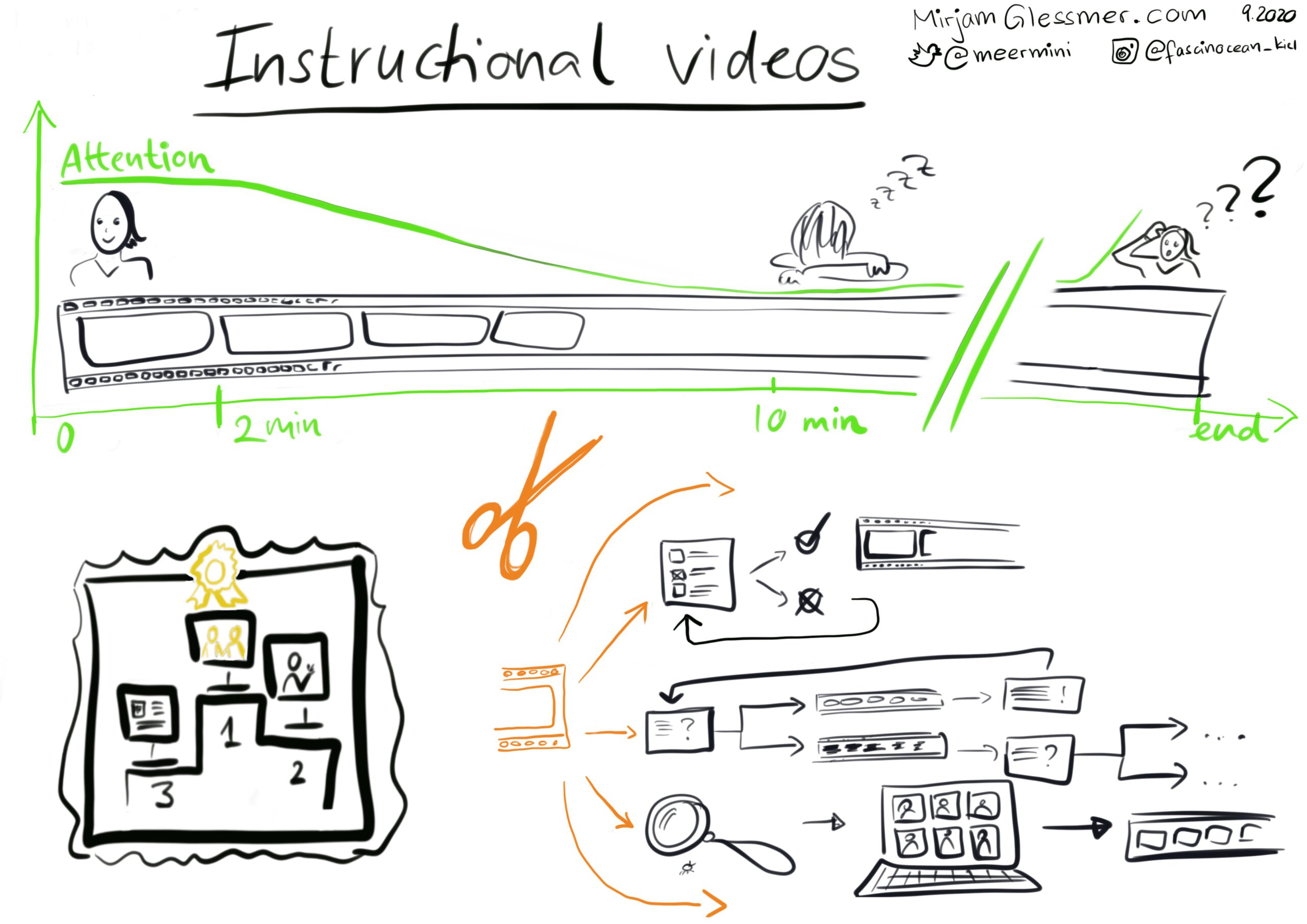

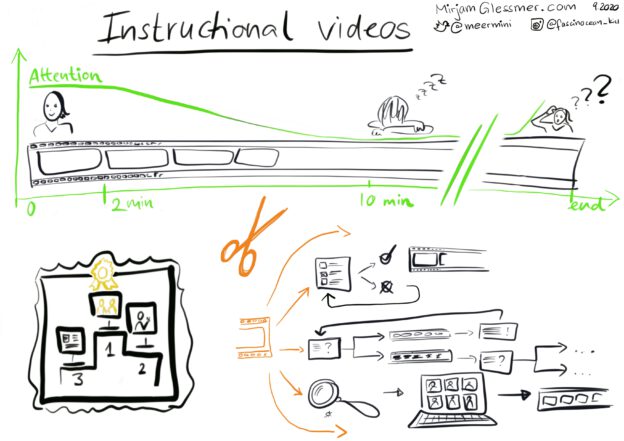

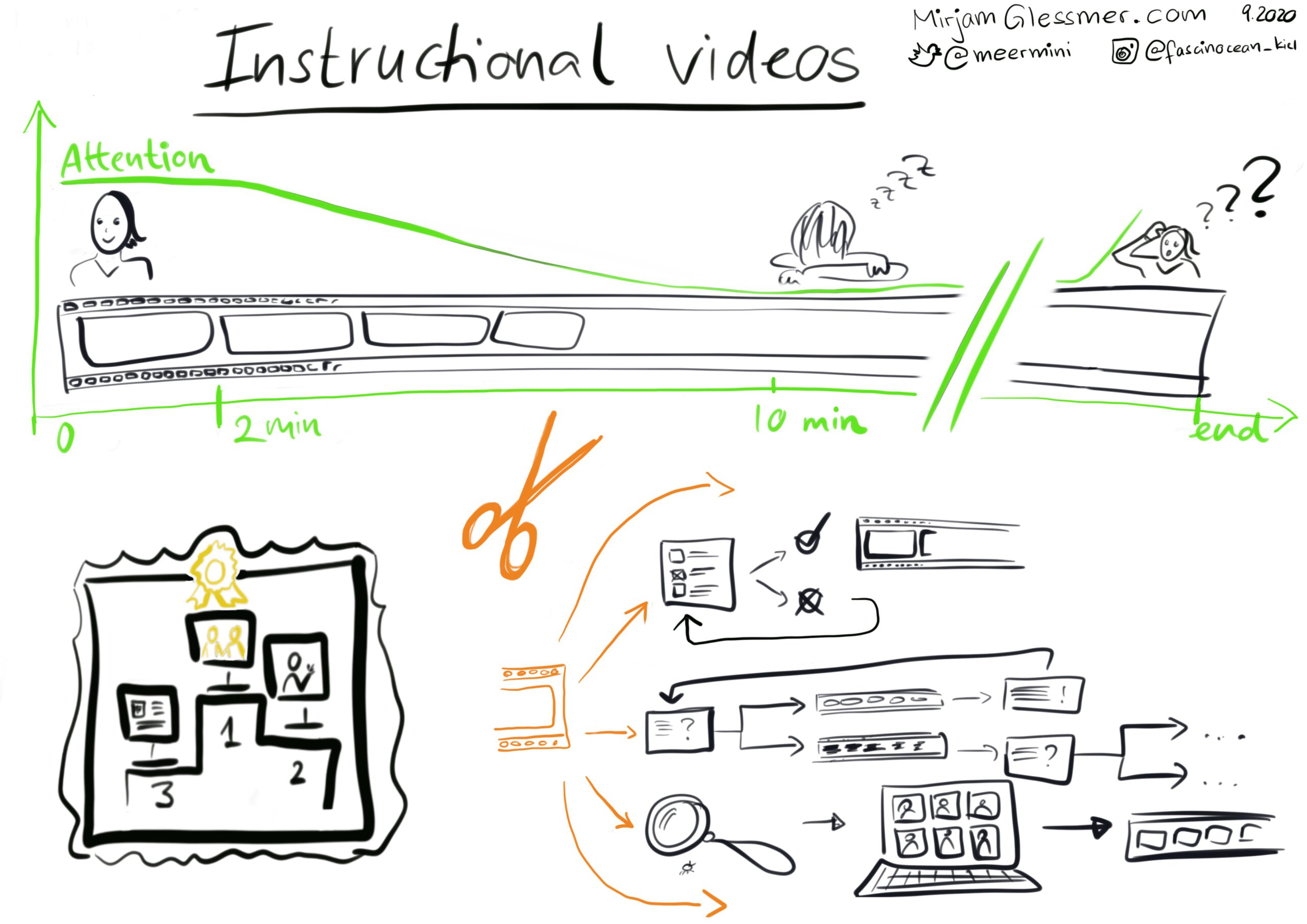

Virtual field courses seems to often mean “videos of the instructor talking”, whether in their office or in the field. When filming instructional videos, for me the most important points to consider are the viewers’ attention spans, and what might keep a viewer engaged.

As for the attention span, there are many different studies that find that the shorter, the better. Of course it always depends on the video and the material and lots of other things, but the best advice would be to really think about whether anything needs to be longer than 15 minutes in one go (unless it is extremely well produced).

In order to keep viewers engaged, it’s really important to not only keep students in the role of “viewers”, but to engage them more actively. But for the periods where they are “just” watching, it seems that it is helpful to have the instructor visible and make them relatable as an authentic person. Especially having more than one instructor that interact with oneanother makes it more engaging and also provides more potential role models to students.

A list of best practices for creating engagement in educational videos is given in Choe et al., 2019; my take-away from that here.

How to motivate students in virtual field courses

Haha, you were hoping for an easy answer here? I think keeping in mind the three basic psychological needs of students that I described in the framework of the self-determination theory (autonomy, competence and relatedness) is extremely important. The better we can find ways to give students opportunities to feel any and all of those, the more motivated they’ll be.

Good-practice examples of virtual field courses

(This section was first called “best-practice”, but then I noticed that I am showing quite a lot of my own work and decided I’d rather take it down a notch ;-))

There are many categorizations possible for the examples I’m showing below, but I went for the continuum from “fully virtual” on the one hand and then “fully synchronous outside” on the other.

Fully virtual

If you are doing a fully virtual field course, no matter whether it is video-based or text based, it’s really helpful to integrate activities that aren’t related to listening or reading, for example:

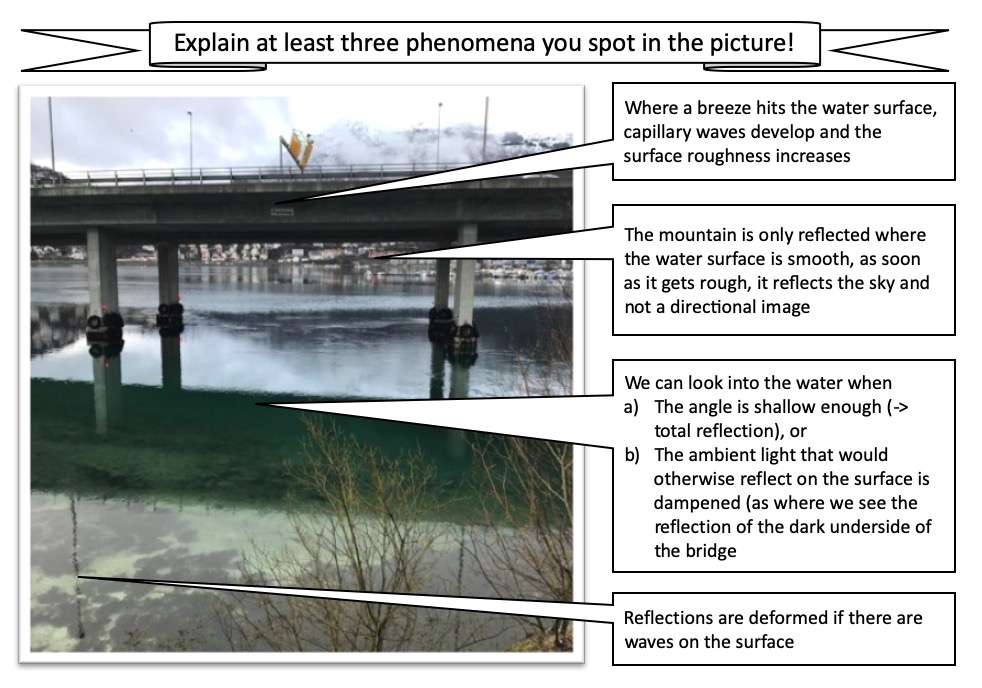

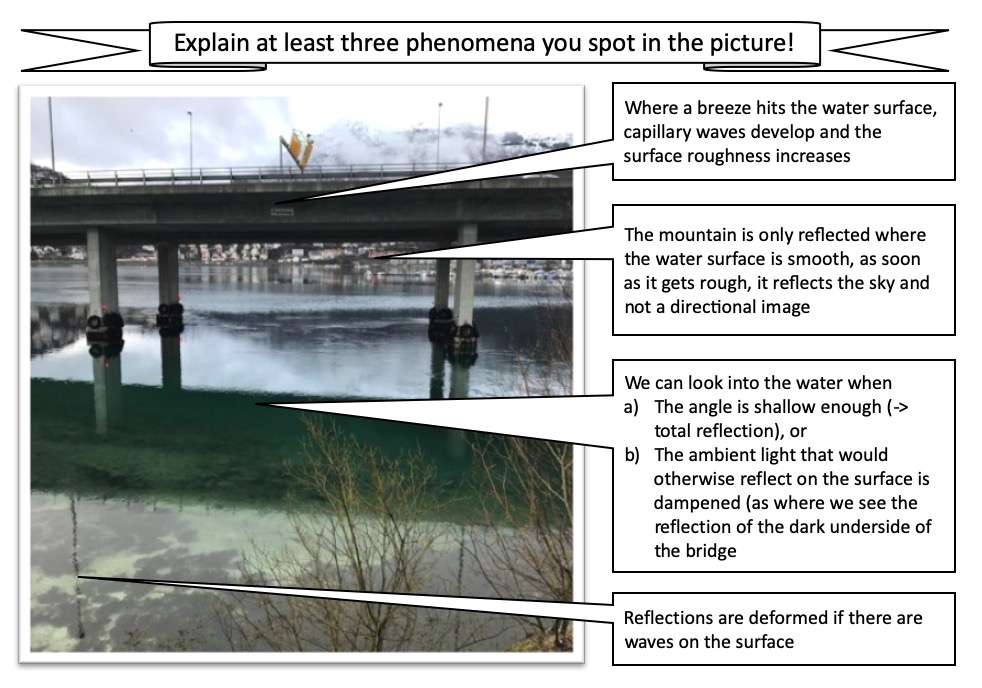

Working with pictures of real examples

Providing students with a picture of a field site, or some example of a process, or some instrumentation that they’ve just learnt about, and asking them to annotate the picture is a quick and easy activity that also helps you gauge the students’ level of understanding. This works well if you just want students doing something else than listening to you for 15 minutes.

Working with simulations

It’s fascinating how many really nice virtual representations exist online on all kinds of topics once one starts looking!

I was very impressed with this virtual arboretum I came across recently. If you were teaching about plants, this might be a neat tool for example when you want students to practice drawing plant features, for example.

Investigating a compilation of media

At the recent #FieldWorkFix conference, we were shown this platform for a virtual site assessment which I found super impressive: It’s basically “only” 360° pictures, movies and audio files that are located on a map, so students can do a virtual walk through a park that they would otherwise have visited. But the way this is done, by for example also including a picture of the parking spot and visitors center, makes it feel very real and relatable, and the other pictures, movies and audio files of the park make it possible to do the real assessment.

Another example that I find extremely inspiring is not of a whole site, but it’s a study guide on ID-ing different kinds of rocks. There is a large visual bank of rocks, each combined with the data that students need to make an ID, for example a scale so one can estimate the real size of the rocks, responses to different acids that give clues about the chemical composition, etc.. It seems incredibly comprehensive and like a lot of fun!

Investigating real data

There are of course also many amazing datasets compiled for different regions, for example Svalbox.no for Svalbard, where students can use gis-systems to access many different kinds of data in a geo-referenced frame. Combined with for example google Earth this can be used for free exploration into many different questions.

Creating the features you want to investigate

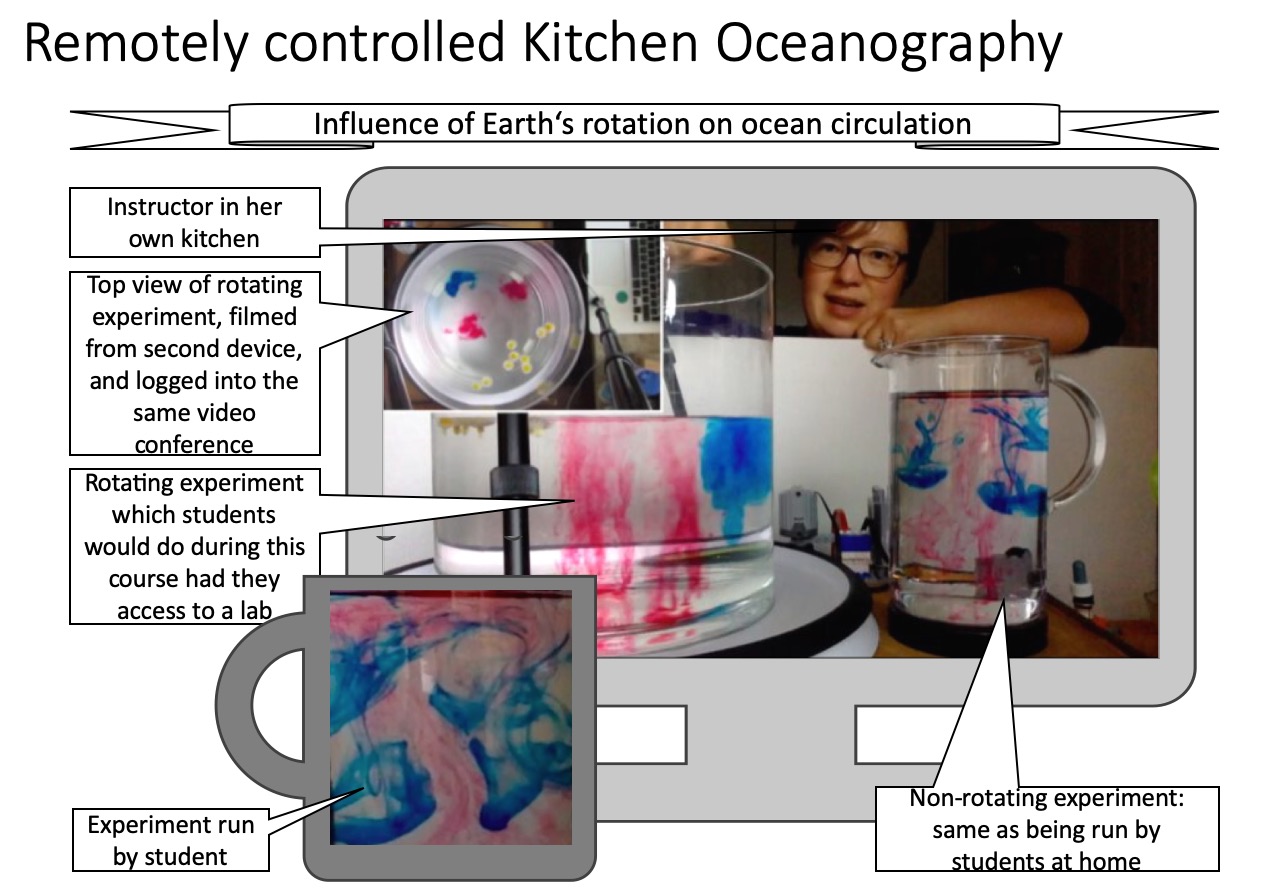

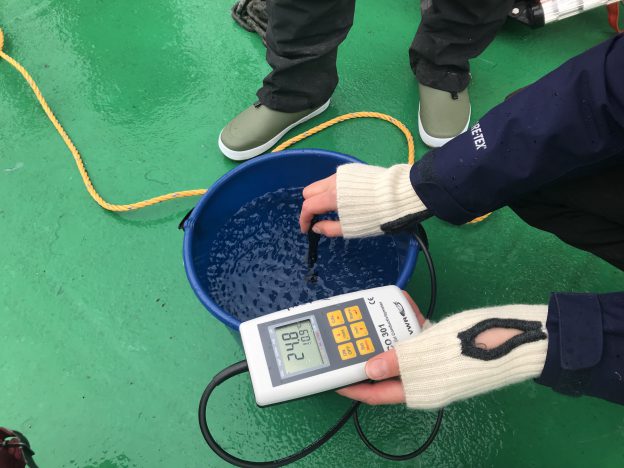

Last not least, if you want students to do some practical work at home in a virtual course, there is always kitchen oceanography, which in this context means hands-on activities that can be done solely with materials that students typically have at home already. It can mean investigating ocean currents in plastic cups with water, ice and black tea (for 24 easy ideas check out my advent calendar), or it can mean using bread or chocolate bars to simulate an investigation into how rocks behave under pressure. Or if you wanted to get fancy, you could even send out materials (e.g. sand samples in small zip lock bags to get a feel of different grain sizes). Doing small hands-on stuff at home can be a great way to change up long days of sitting in front of a computer…

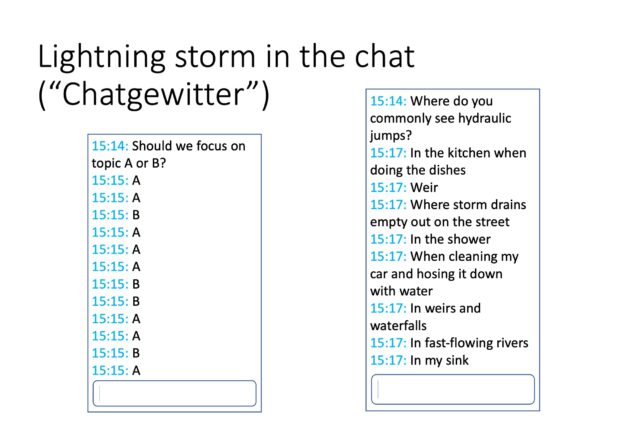

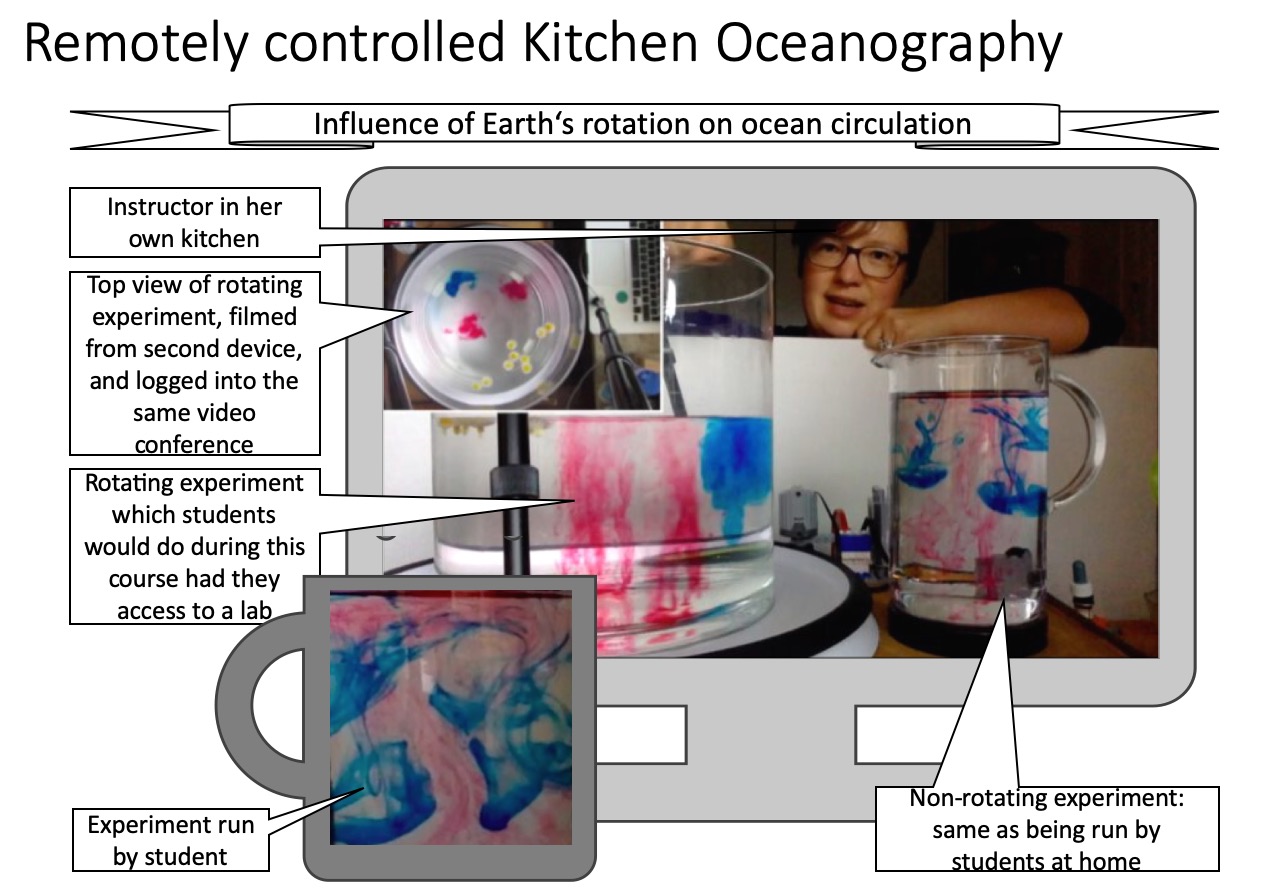

With “remotely controlled kitchen oceanography” we’ve shown how small, hands-on stuff that students do at home can be combined with experiments with more complicated setups, that are streamed from my kitchen. We were all in a video conference and could therefore all see each others’ experiments while being able to really closely look at our own. Doing something similar with an instructor in the field should be easy enough (if the network and weather cooperate).

Virtual with “outdoor” aspects

As much fun as kitchen oceanography breaks are, sometimes it might be even better to get students out the door with a purpose.

Observe something related to your field right outside your door

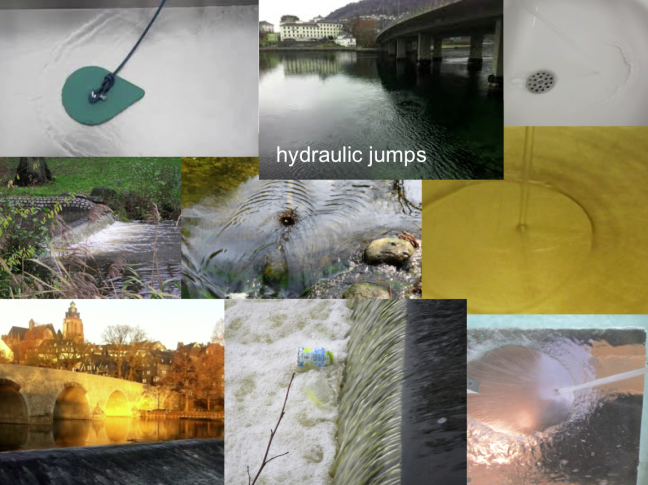

I’ve long been a fan of local fieldwork, i.e. sending students out to discover something related to the course’s topic right outside their door. For examples see for example my post on hydraulic jumps that are everywhere, on #BergenWaveWatching, or on #MoreThanWeeds.

But how to implement it in a virtual field course?

One way to take the pressure off students when doing local fieldwork tasks was shown to us at the #FieldWorkFix conference in this super best practice example that I got to experience myself during a fairly intensive virtual conference day: During the one hour lunch break, we not only had to eat lunch, but were asked to go outside and follow the wandering cards on here. Those are cards that give you instructions for your short walk: “Follow something yellow”, “sit for 2 minutes and observe things around you”, “take a right turn”, that kind of things (I, of course, didn’t follow the instructions because I wanted to see some water during my lunch break). We were also instructed to take pictures of something related to our field course, upload it on a website and write a short description (which I did).

And it was a great experience: Within this one hour, I did manage to eat lunch, go outside, take a picture, upload it, and add a description. This let me get some exercise and oxygen, gave me a purpose for my walk, and also proved how easy and fast these kinds of tasks can be if you don’t feel that you need to go to The Best wave watching spot, see the most exciting plant, whatever, but instead just have to find anything related to the course. And it was great to see all the different pictures of participants coming together! This is a way to introduce the local excursions that I will definitely be using in the future to give students that feeling of competence but also a glimpse of one of the typical feelings of fieldwork: That time is precious and every minute and every observation counts. But that a lot can be gained in a really short time, too!

Outdoor asynchronous

If one of the learning outcomes is to practice observation and classification skills, working with citizen science apps like iNaturalist or the german Naturgucker are great. Both are parts of citizen science projects where everybody can upload pictures and other observations (e.g. audio files) that are then classified either by that person directly or through discussions on the platform. Here students contribute to “real science” by collecting data that is relevant for a larger purpose, and they interact with specialists and thus get feedback and feel part of a bigger community. I don’t know anything like that for my own topics, but in biology those are great tools.

One tool that I really want to use in asynchronous outdoor teaching myself are geocaches. Geocaching is a virtual treasure hunt: small “treasures” (often tiny plastic boxes) are hidden and can be found using an app tht gives clues where to look. Geocaches can also be virtual, and are already used for educational purposes for example as “EarthCaches“. This special form of geocaches has been developed by the Geological Society of America and the goal is to bring people to geologically interesting sites and teach them something related to that site. Wouldn’t it be awesome to do something like that for your class?

Geocaches are peer-reviewed before they appear on the app, so a lower threshold version of the same idea could be QR-codes that you hide in the area you want your students to investigate, and have the QR-codes link to websites that you can easily adapt with the seasons, or update from year to year, or have full and easy control over. Of course you might need to check the QR-codes are still there before you run the class the next year, but this is fairly low-key if you are working close to home. (Close to home being an important caveat: in fully virtual semesters, students might actually not be where you are. Please consider ways to accommodate them!)

Outdoor synchronouns

In the last workshop I ran on virtual field courses, a participant told us about a tour guide system his institute had just bought in order to be able to do in-person excursions. The devil is in the detail, of course (how do you make sure all students can see while still maintaining the necessary distance from each other?), but that sounded like a great idea.

Ideas for assessment

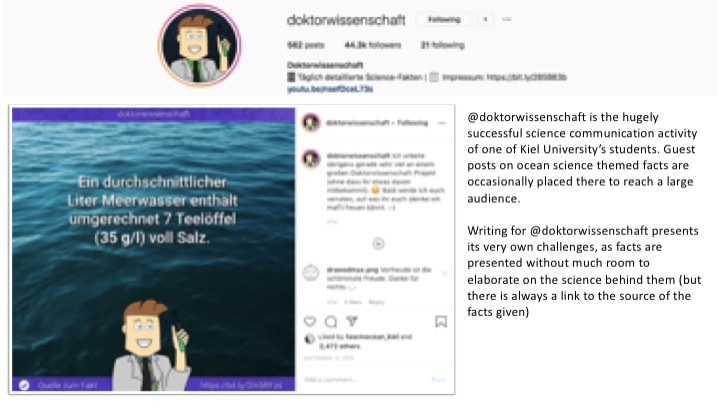

Depending on what is being done during the virtual field courses, traditional forms of assessment might still work, or maybe they need to be adapted. What you could consider is including activities into your assessment that are motivating students in themselves, for example asking them to write Instagram or blog posts (and check out this blog post for a grading rubric for Instagram posts!).

In my experience, writing for a different audience than just one overwhelmed instructor is very motivating to students, both because they can use it to show their friends and family what they are doing all day long, and because social media provides the potential for super positive feedback (check out Robert’s tweet about one of my kitchen oceanography experiments that just received its 330th “like” today!). An assignment like that helps on all three psychological basic needs that help foster intrinsic motivation: feeling autonomous, competent and related. So why not give it a shot?

What is your experience with virtual field courses? Do you have best practice examples to add to this? Please share!

References

Ronny C. Choe, Zorica Scuric, Ethan Eshkol, Sean Cruser, Ava Arndt, Robert Cox, Shannon P. Toma, Casey Shapiro, Marc Levis-Fitzgerald, Greg Barnes, and H. Crosbie (2019). “Student Satisfaction and Learning Outcomes in Asynchronous Online Lecture Videos”, CBE—Life Sciences Education, Vol. 18, No. 4. Published Online: 1 Nov 2019

https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.18-08-0171

Fedesco, H. N., Cavin, D., Henares, R. (2020). Field-based Learning in Higher Education: Exploring the Benefits and Possibilities. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, Vol. 20, No. 1, April 2020, pp.65-84. doi: 10.14434/josotl.v20i1.24877

Finkelstein, N. D., Adams, W. K., Keller, C. J., Kohl, P. B., Perkins, K. K., Podolefsky, N. S., Reid S., LeMaster. R. (2005). When learning about the real world is better done virtually: A study of substituting computer simulations for laboratory equipment. Physical review special topics – Physics education research 1, 010103

Giles, S., Jackson, C. & Stephen, N. Barriers to fieldwork in undergraduate geoscience degrees. Nat Rev Earth Environ 1, 77–78 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43017-020-0022-5

Larsen, C., Walsh, C., Almond, N., & Myers, C. (2017). The “real value” of field trips in the early weeks of higher education: the student perspective. Educational Studies, 43(1), 110-121.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2017). Self-determination theory: Basic psychological needs in motivation, development, and wellness. New York: Guilford