The “other” double-diffusive mixing process.

After having talked extensively about double diffusive mixing in my courses, I tend to assume that students not only remember that there is such thing as double-diffusive mixing, but that they also remember our discussions on how the process works, and that they would be able to transfer this to processes other than salt fingering.

So in two courses (at different universities) I asked students in the exam to describe what would happen in a stably stratified body of water, where cold and fresh water overlies warm and salty water. And in both courses I have been surprised (read: shocked) by the responses I got.

The by far most common response goes along these lines: “Cold water is denser than warm water, so it will sink to the bottom and the warm water will rise”.

What I find frustrating about this (besides the fact that they didn’t notice that I clearly stated in the question that the stratification was stably stratified) is that whenever I talked about density, I mention how density depends on both temperature and salinity.

The next most common response is then this: “Heat diffuses a factor 100 faster than salt. Hence, salt fingers will form at the interface”. This answer then continues on describing salt fingering and never even mentions that the stratification I described in the question was actually the opposite one to the one they are assuming. So here, students clearly jumped to the conclusion that if I bothered describing a stratification, it clearly had to be the one for my favorite process (even though during those discussions I made sure to mention diffusive layering, too, but without talking it through in as much detail as salt fingering).

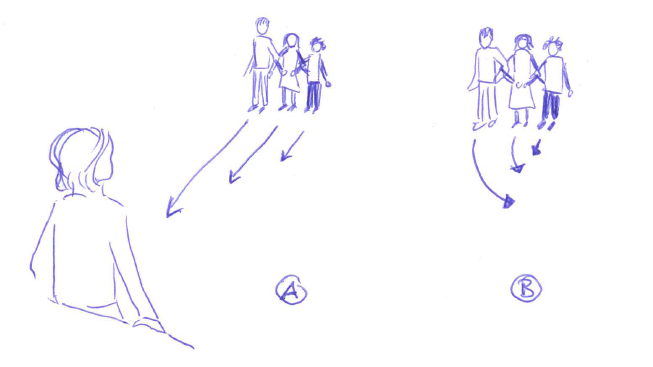

But then there are always students (usually the ones who don’t have a lot of confidence in their oceanography skills) who take the questions I ask at face value. Those are the students who go on to write something like this (numbering referring to the sketch below):

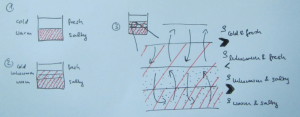

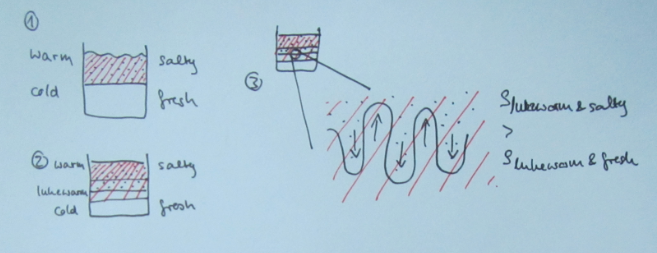

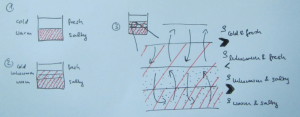

1) The initial stratification is stable in density, with cold and fresh water over warm and salty water. This means that the salinity stratification outweighs the temperature stratification in terms of density.

2) Since temperature diffuses a factor 100 faster than salinity, a thin layer with an intermediate temperature will form around the interface in salinity, that will persist for a while.

3) Focussing above the interface now, we have a stratification where cold and fresh water overlies lukewarm and fresh water. This stratification is hence unstable in temperature and convective overturning will occur. Below the interface, a similarly unstable layer has formed: lukewarm and salty water over warm and salty water. Again, convective overturning will occur.

The thickness of those layers depends on the initial temperature stratification and on how quickly temperature exchange happens during the overturning. In the end, two new temperature interfaces will have formed.

Sketch of the diffusive layering process. The red shading indicates warmer temperatures, the black dots indicate higher salinities.

And yes – that is exactly the response I wanted to hear!

So why do only so few students answer this question correctly? Don’t they understand that when I talk about salt fingering it is only an example of a double-diffusive process and not the only double-diffusive process there is? That was my initial thought after I saw the exams in the first class. So for the second class, I made sure to mention diffusive layering even more, and to explicitly say that I was talking through only one of the processes and that it might be helpful if they went through the other one on their own. Yet in the exams, the results did not change. And I have no idea. Do you? Then please let me know!