I had to do the complete series of experiments, of course…

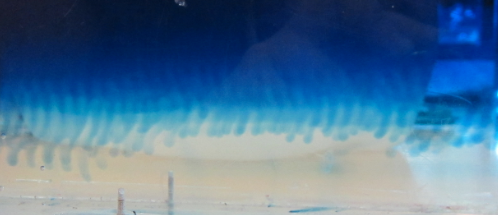

The other day I mentioned that I had used salt from my kitchen for the “ice cubes melting in fresh and salt water” experiment, and that that salt was the super healthy one that was both iodized and containing folic acid. And what happened is that the experiment looked like I was using milk. Not what I had envisioned.

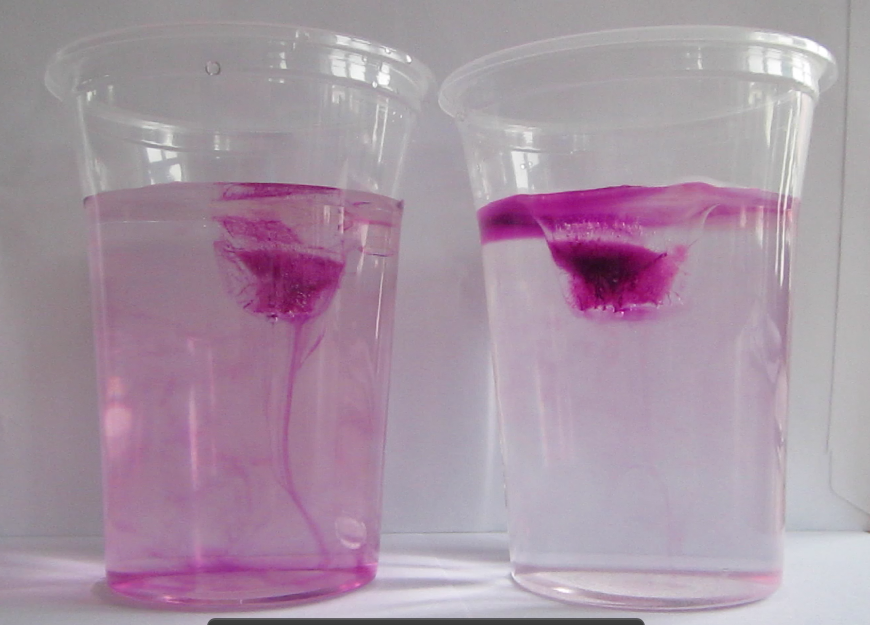

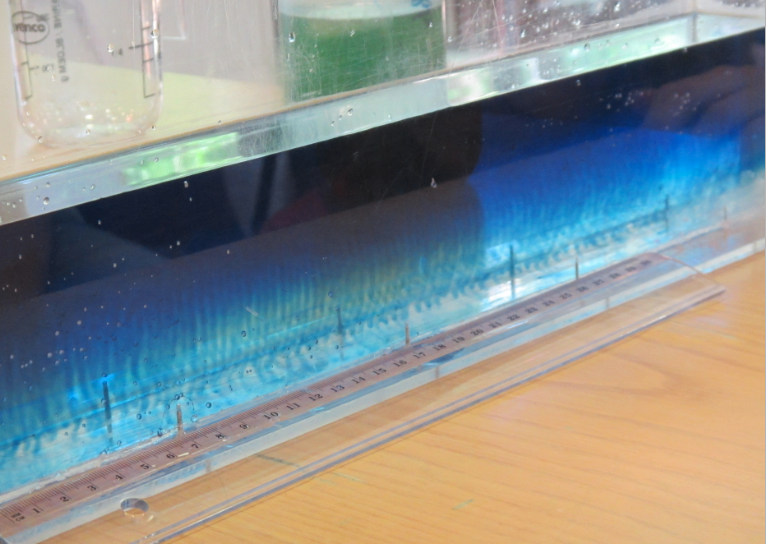

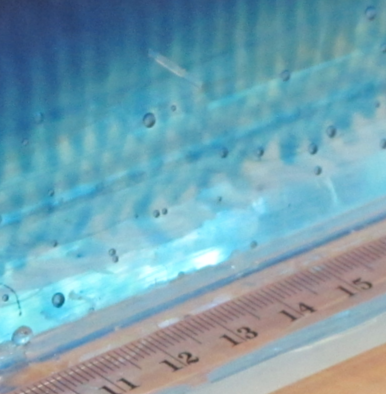

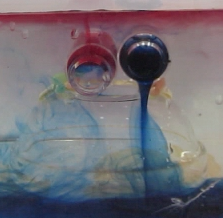

Since I had often before used just regular table salt – which is usually iodized – I was intrigued by the opaqueness that seemed to be due to the addition of folic acid. Or was it? That I had never noticed the milky-ness of the salt water didn’t necessarily mean that it had not been milky before. So this is what the same experiment looks like if regular iodized table salt is used:

Ice cubes melting in fresh water (left) and in iodized-salt water (right). Turbulence in the freshwater beaker due to me stirring (don’t ask)

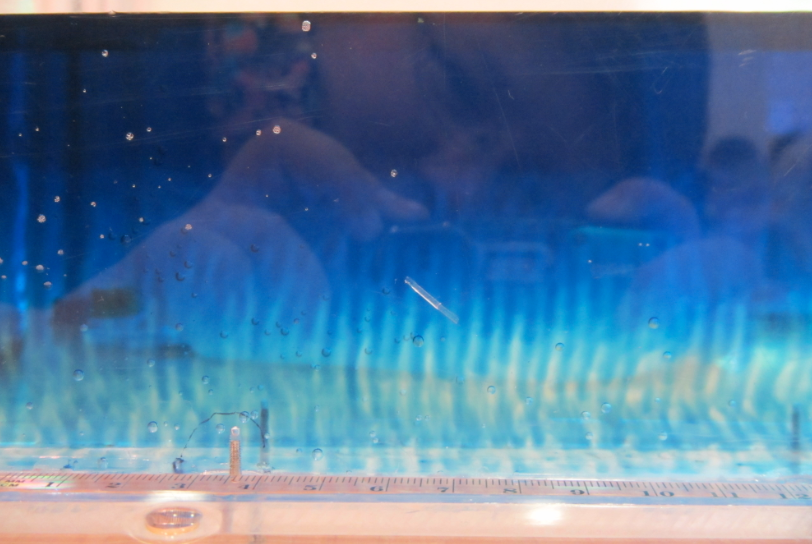

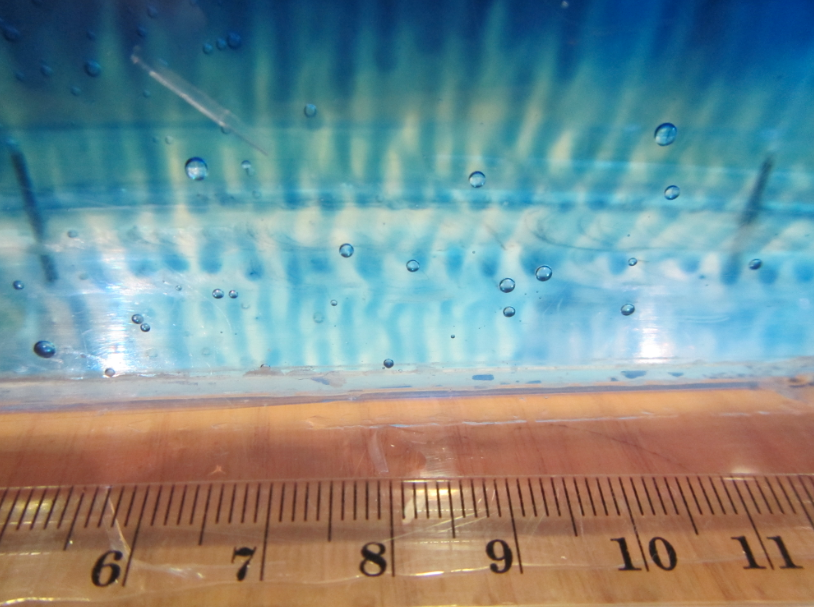

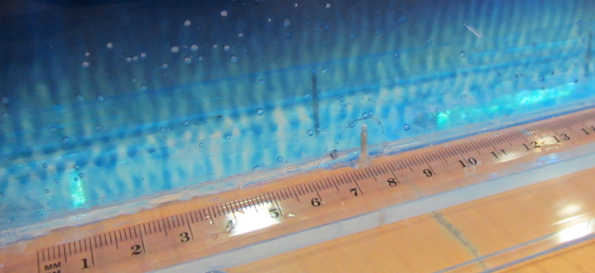

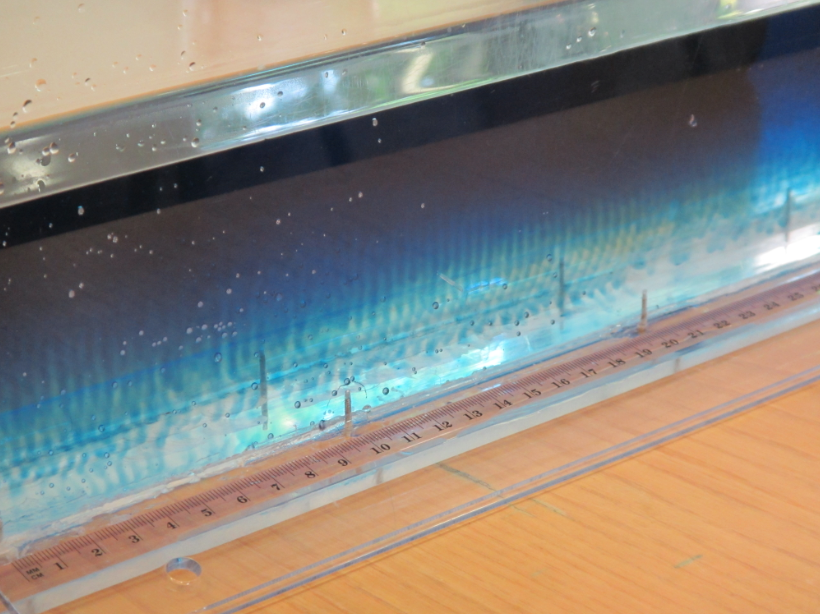

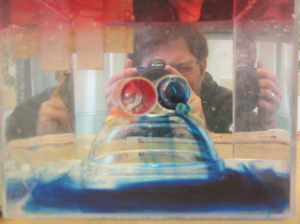

In the literature it is always recommended to use kosher salt for experiments. Kosher meaning in this context that the salt should be only NaCl with no other additions. I happened to have some at hand after having bought it for the “teaching oceanography” workshop in San Francisco last year (after the salt that I brought for the workshop didn’t make it to the US. Long story). So this is what that looks like:

In summary: Folic acid is what makes the salt water look opaque – but iodized salt is completely fine for tank experiments. I think it’s tiny air bubbles that cling to something folic acid-y, but I have no clue what is going on. I noticed that the dusty stuff settled down over night (so the top experiment here is a lot clearer than the experiment I ran with the same batch of water the day before), but even the next day the water wasn’t completely clear.

Anyway, now we know. And I came out of this series with more movies of ice cubes melting in fresh water and salt water!

Links to previous posts on the topic after the cut.

[Edit: Using my mom’s iodized, but not folic acid containing, table salt leads to milky water, too. So there you have it. I have no clue what is going on!]