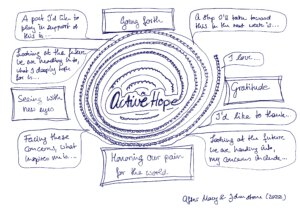

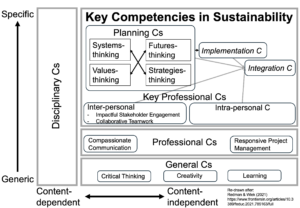

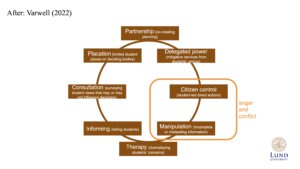

Thinking about citizen- and active student participation, inspired by Arnstein (1969), Varwell (2022), Biesta (2026), and others

Since listening to Gerry’s defense of his PhD thesis the other day, I have been thinking about partnership a lot, and how we need to practice partnership also in order…