Workshop on PBL, using the upcoming solar eclipse (on Friday!) as a case study.

I am currently attending a workshop run by one of my all-time favorite colleagues, Marisa, on Problem-Based Learning. The workshop is aimed at people who want to use PBL in their teaching, and is split into three sessions. By pure dumb luck I realized that the second session will be on March 20th, the day of the solar eclipse. So of course I had to hijack the workshop a make her write a case study on that topic! (We really had to – I don’t think we could expect anyone to sit inside and work on some old case study if a solar eclipse was happening outside).

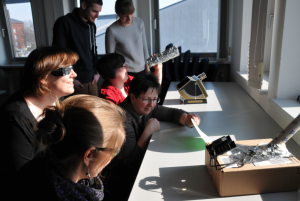

Marisa teaching us how to use PBL

I am going to use that case and that workshop to talk you through the concept of problem–based learning.

The solar eclipse case.

In a nutshell, this is our case: Imagine it’s your god-daughter’s 7th Birthday on March 20th, 2015. She’s super into astronomy and you want to watch the solar eclipse with her. You don’t want to buy equipment, but you know she gets very excited and therefore need to make sure she’s ok. What do you do?

The seven steps of PBL

During the first workshop last Friday, we went through steps 1 to 5 of the Maastricht PBL model. Before the first step, Marisa gave a brief introduction to the method, and picked someone to document the discussion. Usually you would also pick someone to lead the discussion, but since we were all inexperienced with the method, Marisa took that role herself – something she’s recommend we do the first time we do PBL in class, too.

1. Clarifying terms

In this step, participants read the case and make sure they understand all the terms. For example, in our case, people discussed “equipment”, “household items” (which we had said they could only use for their equipment) and “solar eclipse”. Discussion here is merely to clarify that everybody reads the case the same way – if terms came up that we couldn’t come to an agreement on in this step, we wouldn’t do research now but postpone it to step 2.

2. Defining the problem

Here, all possible questions that we might want to answer during this PBL case were collected. Again, we were not answering anything yet, just collecting facets of the problem that people thought were interesting and should be investigated. For us, this meant for example “what can we use to protect our eyes?”, “will we need to make sure our god-daughter gets out of school so we can take her to watch the solar eclipse?”, “how much background do we want to convey to her?”.

The second question – about how we’d get her out of school, was answered by Marisa: We can assume that that is not an issue. So here the tutor can interfere and guide the discussion if it leads too far from the desired learning goals.

3. Brainstorming

In this step, we collect all kinds of possible answers to the questions brought up in step 2. Since this is still a brainstorming phase, they should not be judged or discussed, just collected. So for example we came up with different activities that we could pursue with her in case the weather was bad or possibly for giving her a bit of a theoretical background before watching the solar eclipse.

4. Structuring and hypothesis

Now we took keywords from phase 2 and 3 and sorted them. As a group, we didn’t actually decide on whether to sort by importance or by logical order of steps (so for example if we looked at the weather forecast and were sure we would not be able to see anything, we would not need to look into eye protection, however eye protection seems really important and also fun to investigate). It was interesting to see how it led to quite some frustration that people weren’t sorting following the same criteria, yet nobody “made” the group decide which criteria they wanted to use.

5. Learning objectives

In this step, the structure found in step 4 is being written up in complete questions – those are the questions that will be answered later.

So all that is missing now are steps 6, “Searching for Information”, which students are currently doing and which should be finished by Friday, and 7, “Synthesis”, which we will do on Friday.

Working with people who will later use PBL in their teaching, one of the important points was to let them experience what it is like to be a student in a PBL setting. Seeing how frustrated some people got, and how we really often didn’t know what to do was super important to get an idea of what it would be like for our students.

Until now, nothing “step 6″ish has happened. I am curious how much work outside of the workshop is going to get done, and if it will get done by a group or by individuals. I’m kinda itching to get the group together to discuss, but I’m going to try to not do it and see what happens.

I’ll keep you posted on my experience with step 6 and 7, on how I can see myself using this method, and on how things turn out :-)