Examples of different kinds of multiple choice questions that you could use.

Multiple choice questions are a tool that is used a lot with clickers or even on exams, but they are especially on my mind these days because I’ve been exposed to them on the student side for the first time in a very long time. I’m taking the “Introduction to evidence-based STEM teaching” course on coursera, and taking the tests there, I noticed how I fall into the typical student behavior: working backwards from the given answers, rather than actually thinking about how I would answer the question first, and then looking at the possible answers. And it is amazing how high you can score just by looking at which answer contains certain key words, or whether the grammatical structure of the answers matches the question… Scary!

So now I’m thinking again about how to ask good multiple choice questions. This post is heavily inspired by a book chapter that I read a while ago in preparation for a teaching innovation: “Teaching with Classroom Response Systems – creating active learning environments” by Derek Bruff (2009). While you should really go and read the book, I will talk you through his “taxonomy of clicker questions” (chapter 3 of said book), using my own random oceanography examples.

I’m focusing here on content questions in contrast to process questions (which would deal with the learning process itself, i.e. who the students are, how they feel about things, how well they think they understand, …).

Content questions can be asked at different levels of difficulty, and also for different purposes.

Recall of facts

In the most basic case, content questions are about recall of facts on a basic level.

Which ocean has the largest surface area?

A: the Indian Ocean

B: the Pacific Ocean

C: the Atlantic Ocean

D: the Southern Ocean

E: I don’t know*

Recall questions are more useful for assessing learning than for engaging students in discussions. But they can also be very helpful at the beginning of class periods or new topics to help students activate prior knowledge, which will then help them connect new concepts to already existing concepts, thereby supporting deep learning. They can also help an instructor understand students’ previous knowledge in order to assess what kind of foundation can be built on with future instruction.

Conceptual Understanding Questions

Answering conceptual understanding questions requires higher-level cognitive functions than purely recalling facts. Now, in addition to recalling, students need to understand concepts. Useful “wrong” answers are typically based on student misconceptions. Offering typical student misconceptions as possible answers is a way to elicit a misconception, so it can be confronted and resolved in a next step.

At a water depth of 2 meters, which of the following statements is correct?

A: A wave with a wavelength of 10 m is faster than one with 20 m.

B: A wave with a wavelength of 10 m is slower than one with 20 m.

C: A wave with a wavelength of 10 m is as fast as one with 20 m.

D: I don’t know*

It is important to ask yourself whether a question actually is a conceptual understanding question or whether it could, in fact, be answered correctly purely based on good listening or reading. Is a correct answer really an indication of a good grasp of the underlying concept?

Classification questions

Classification questions assess understanding of concepts by having students decide which answer choices fall into a given category.

Which of the following are examples of freak waves?

A: The 2004 Indian Ocean Boxing Day tsunami.

B: A wave with a wave height of more than twice the significant wave height.

C: A wave with a wave height of more than five times the significant wave height.

D: The highest third of waves.

E: I don’t know*

Or asked in a different way, focussing on which characteristics define a category:

Which of the following is a characteristic of a freak wave?

A: The wavelength is 100 times greater than the water depth

B: The wave height is more than twice the significant wave height

C: Height is in the top third of wave heights

D: I don’t know*

This type of questions is useful when students will have to use given definitions, because they practice to see whether or not a classification (and hence a method or approach) is applicable to a given situation.

Explanation of concepts

In the “explanation of concepts” type of question, students have to weigh different definitions of a given phenomenon and find the one that describes it best.

Which of the following best describes the significant wave height?

A: The significant wave height is the mean wave height of the highest third of waves

B: The significant wave height is the mean over the height of all waves

C: The significant wave height is the mean wave height of the highest tenth of waves

E: I don’t know*

Instead of offering your own answer choices here, you could also ask students to explain a concept in their own words and then, in a next step, have them vote on which of those is the best explanation.

Concept question

These questions test the understanding of a concept without, at the same time, testing computational skills. If the same question was asked giving numbers for the weights and distances, students might calculate the correct answer without actually having understood the concepts behind it.

To feel the same pressure at the bottom, two water-filled vessels must have…

A: the same height

B: the same volume

C: the same surface area

D: Both the same volume and height

E: I don’t know*

Or another example:

If you wanted to create salt fingers that formed as quickly as possible and lasted for as long as possible, how would you set up the experiment?

A: Using temperature and salt.

B: Using temperature and sugar.

C: Using salt and sugar.

D: I don’t know.*

Ratio reasoning question

Ratio reasoning questions let you test the understanding of a concept without testing maths skills, too.

You are sitting on a seesaw with your niece, who weighs half of your weight. In order to be able to seesaw nicely, you have to sit…

A: approximately twice as far from the mounting as she does.

B: approximately at the same distance from the mounting as she does.

C: approximately half as far from the mounting as she does.

D: I don’t know.*

If the concept is understood, students can answer this without having been given numbers to calculate and then decide.

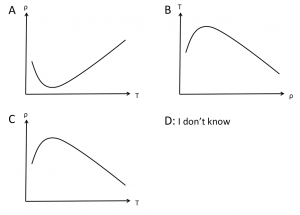

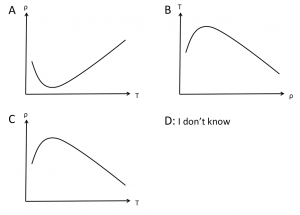

Another type of question that I like:

Which of the following sketches best describes the density maximum in freshwater?

If students have a firm grasp of the concept, they will be able to pick which of the graphs represents a given concept. If they are not sure what is shown on which axis, you can be pretty sure they do not understand the concept yet.

Application questions

Application questions further integrative learning, where students bring together ideas from multiple sessions or courses.

Which has the biggest effect on sea surface temperature?

A: Heating through radiation from the sun.

B: Evaporative cooling.

C: Mixing with other water masses.

D: Radiation to space during night time.

E: I don’t know.*

Students here have the chance to discuss the effect sizes depending on multiple factors, like for example the geographical setting, the season, or others.

Procedural questions

Here students apply a procedure to come to the correct answer.

The phase velocity of a shallow water wave is 7 m/s. How deep is the water?

A: 0.5 m

B: 1 m

C: 5 m

D: 10 m

E: 50 m

F: I don’t know*

Prediction question

Have students predict something to force them to commit to once choice so they are more invested in the outcome of an experiment (or even explanation) later on.

Which will melt faster, an ice cube in fresh water or in salt water?

A: The one in fresh water.

B: The one in salt water.

C: No difference.

D: I don’t know.*

Or:

Will the radius of a ball launched on a rotating table increase or decrease as the speed of the rotation is increased?

A: Increase.

B: Decrease.

C: Stay the same.

D: Depends on the speed the ball is launched with.

E. I don’t know.*

Critical thinking questions

Critical thinking questions do not necessarily have one right answer. Instead, they provide opportunities for discussion by suggesting several valid answers.

Iron fertilization of the ocean should be…

A: legal, because the possible benefits outweigh the possible risks

B: illegal, because we cannot possibly estimate the risks involved in manipulating a system as complex as the ecosystem

C: legal, because we are running a huge experiment by introducing anthropogenic CO2 into the atmosphere, so continuing with the experiment is only consequent

D: illegal, because nobody should have the right to manipulate the climate for the whole planet

For critical thinking questions, the discussion step (which is always recommended!) is even more important, because now it isn’t about finding a correct answer, but about developing valid reasoning and about practicing discussion skills.

Another way to focus on the reasoning is shown in this example:

As waves travel into shallower water, the wave length has to decrease

I. because the wave is slowed down by friction with the bottom.

II. because transformation between kinetic and potential energy is taking place.

III. because the period stays constant.

A: only I

B: only II

C: only III

D: I and II

E: II and III

F: I and III

G: I, II, and III

H: I don’t know*

Of course, in the example above you wouldn’t have to offer all possible combinations as options, but you can pick as many as you like!

One best answer question

Choose one best answer out of several possible answers that all have their merits.

Your rosette only lets you sample 8 bottles before you have to bring it up on deck. You are interested in a high resolution profile, but also want to survey a large area. You decide to

A: take samples repeatedly at each station to have a high vertical resolution

B: only do one cast per station in order to cover a larger geographical range

C: look at the data at each station to determine what to do on the next station

In this case, there is no one correct answer, since the sampling strategy depends on the question you are investigating. But discussing different situations and which of the strategies above might be useful for what situation is a great exercise.

And for those of you who are interested in even more multiple choice question examples, check out the post on multiple choice questions at different Bloom levels.

—

* while you would probably not want to offer this option in a graded assessment, in a classroom setting that is about formative assessment or feedback, remember to include this option! Giving that option avoids wild guessing and gives you a clearer feedback on whether or not students know (or think they know) the answer.