A solution for the siphon problem of the fjord circulation experiment.

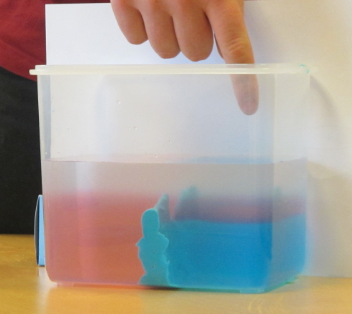

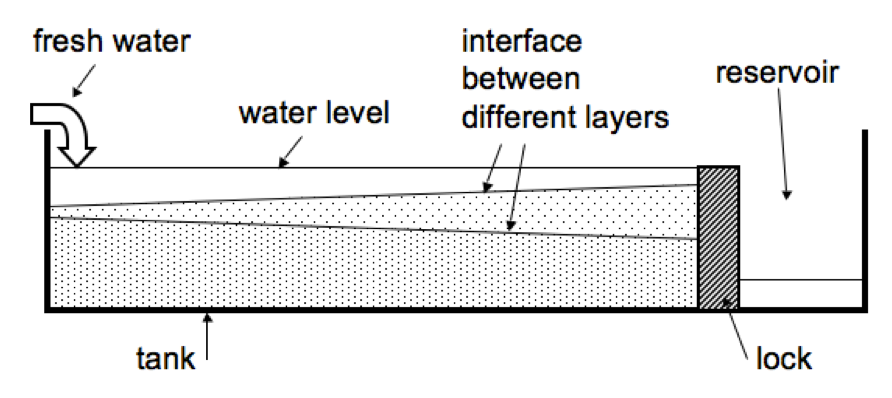

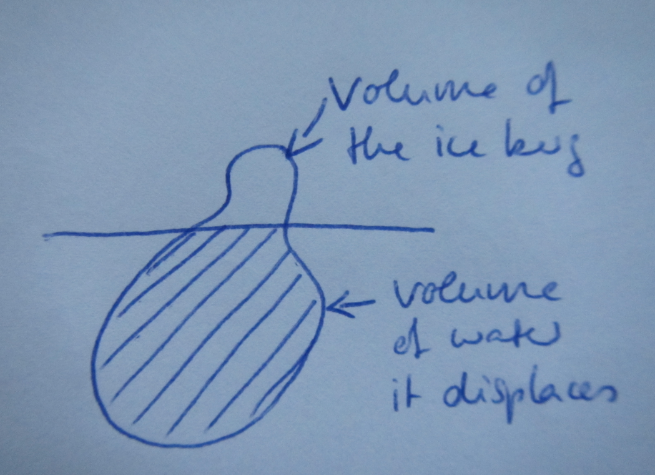

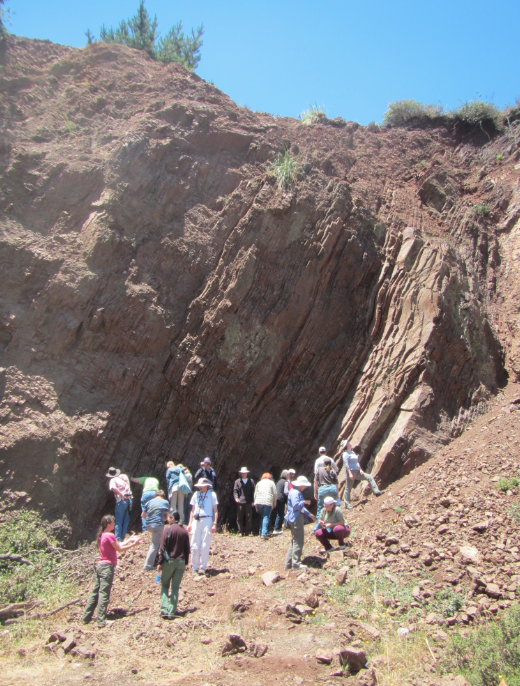

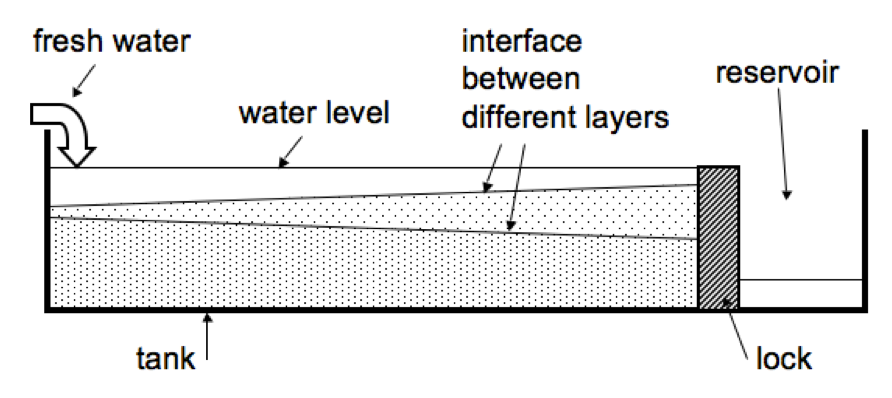

After having run the fjord circulation experiments for several years in a row with several groups of students each year, Pierre and I finally figured out a good way to keep the water level in the tank constant. As you might remember from the sketch in the previous post or can see in the figure below, initially we used to have the tank separated in a main compartment and a reservoir.

But there were a couple of problems associated with this setup. Once, the lock separating the two parts of the tank fell over during the experiment. Then there are bound to be leaks. Sometimes we forget to empty the reservoir and the water level rises to critical levels. In short, it’s a hassle.

So the next year, we decided to run the experiment in a big sink and tip the tank slightly, so that water would just flow out at the lower end at the same rate that it was being added on the other side. Which kinda worked, but it was messy.

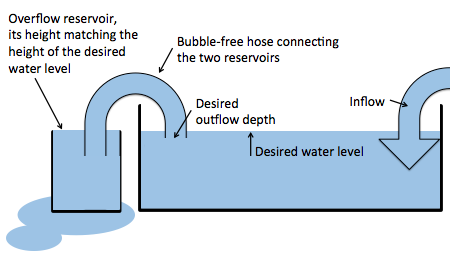

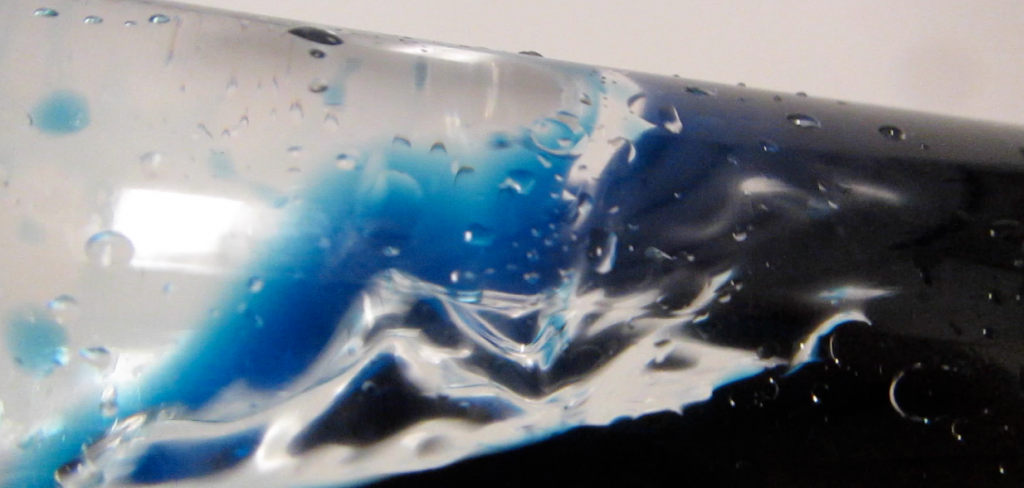

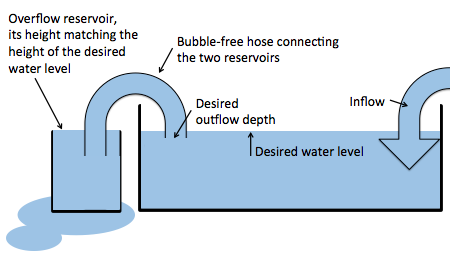

So this year, we came up with the perfect solution. The experiment is still being run in a sink, but now a hose, completely filled with water, connects the main tank with a beaker. The hight of the rim of the beaker is set to the desired water level of the big tank. Now when we add water to the big tank, there is an (almost – if the hose isn’t wide enough) instant outflow, so the water level in the tank stays the same.

New setup: A bubble-free hose connecting the tank and a reservoir to regulate the water level in the tank.

This way, we also get to regulate the depth from where the outflowing water is being removed. Neat, isn’t it?