Welcome to this #WaveWatchingWednesday: Lots of wave pics last week on my Insta @fascinocean_kiel!

Welcome to this #WaveWatchingWednesday: Lots of wave pics last week on my Insta @fascinocean_kiel!

Welcome to #WaveWatchingWednesday, my series in which I share my daily #WaveWatching pics from my Instagram @fascinocean_kiel to this blog!

‘Active Learning’ is frequently used in relation to university teaching, especially in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) subjects where expository lecturing is still a common means of instruction, especially in theoretical courses. However, many different activities and types of activities can be assigned this label. This review article examines the educational research and development literature in 7 subject areas (Astronomy, Biology, Chemistry, Engineering, Geography, Geosciences and Physics) to explore exactly what is meant by ‘active learning’, its core principles and defining characteristics.

Active Learning is often presented or described as a means of increasing student engagement in a teaching situation. ‘Student engagement’ is another poorly defined term, but is usually taken to involve four aspects: social-behavioural (participation in sessions and interactions with other students); cognitive (reflective thought); emotional and agentic (taking responsibility). In this way, ‘Active Learning’ relates to the opportunities that students have to construct their knowledge. On the other hand, and in relation to practice, Active Learning is often presented as the antithesis of student passivity and traditional expository lecturing in which student activity is limited to taking notes. This characterisation is related the behaviour of students in a session.

Most articles and reviews reporting the positive impact of Active Learning on students’ learning don’t define what Active Learning is. Instead, most either list example activities or specify what Active Learning is not. This negative definition introduces an apparent dichotomy which is not as clear as it may initially appear. In fact, short presentations are an important element of many ‘Active Learning’ scenarios: it is the continuous linear presentation of information that is problematic. Most teaching staff promote interactivity and provide opportunities for both individual and social construction of knowledge while making relatively small changes to previously presentation-based lectures.

That said, the amount of class time in which students are interacting directly with the material does matter. One example of measurement of the use and impact of Active Learning strategies (or activities that require students to interact with the material they are learning) in relation to conceptual understanding of Light and Spectroscopy found that high learning gains occur when at least 25% of scheduled class time is spent by students on Active Learning strategies. Moreover, the quality of the activities and their delivery, and the commitment of both students and staff to their use, are also seen as potentially important elements in achieving improved learning.

In order to develop an understanding of what Active Learning actually means, groups in seven disciplinary areas reviewed the discipline-specific literature, and the perspectives were then integrated into a common definition. The research found that presentations of Active Learning in terms of either students’ construction of knowledge via engagement, or in contrast to expository lecturing were used within the disciplines, although the discipline-specific definitions varied. For example, the geosciences definition of Active Learning was:

”Active learning involves situations in which students are engaged in the knowledge-building process. Engagement is manifest in many forms, including cognitive, emotional, behavioural, and agentic, with cognitive engagement being the primary focus in effective active learning,”

while the physics definition was that:

”Active learning encompasses any mode of instruction that does not involve passive student lectures, recipe labs, and algorithmic problem solving (i.e., traditional forms of instruction in physics). It often involves students working in small groups during class to interact with peers and/or the instructor.”

The composite definition to which these contributed is that:

”Active learning is a classroom situation in which the instructor and instructional activities explicitly afford students agency for their learning. In undergraduate STEM instruction, it involves increased levels of engagement with (a) direct experiences of phenomena, (b) scientific data providing evidence about phenomena, (c) scientific models that serve as representations of phenomena, and (d) domain-specific practices that guide the scientific interpretation of observations, analysis of data, and construction and application of models.”

The authors next considered how teaching and learning situations could be understood in terms of the participants and their actions (Figure 1 of the paper). ‘Traditional, lecture-based’ delivery is modelled as a situation where the teacher has direct experience of disciplinary practices, access to data and models, and then filters these into a simplified form presented to the students. Meanwhile, in an Active Learning model students construct their knowledge of the discipline through their own interaction with the elements of the discipline: its practices, data and models. This knowledge is refined through discussion with peers and teaching staff (relative experts within the discipline), and self-reflection.

The concluding sections remark on the typical focus of Discipline Based Educational Research, and reiterate that student isolation (lack of opportunities to discuss concepts and develop understanding) and uninterrupted expository lecturing are both unhelpful to learning, but that ”there is no single instructional strategy that will work across all situations.”

The Curious Constrauct of Active Learning

D. Lombardi, T. F. Shipley and discipline teams.

Psychological Science in the Public Interest. 2021, 22 (1) 8-43

https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1529100620973974

There is a whole body of “historical” research by Trigwell and Prosser and co-authors that I’ve successfully ignored until now, but that is being referenced in conversations around me so much that I cannot longer ignore it. So I read a couple of articles that — I hope — give me a good overview over their body of work, which I’ll summarise here.

A colleague recently sent me a great article by Peter Kirn: “So yeah, let’s just use plug and socket — industry group recommends obvious change in terminology“. In the article, it is pointed out that the “male” and “female” terminology, referring to and how cables are connected together, is problematic and should be avoided in any environment that wants to feel welcoming to everybody, and that there are alternative terms readily available that are not any less clear, but don’t evoke uncomfortable feelings in people. This prompted me to do a search on other terms that might have similar negative effects on other people and that I might not be aware of, and here are a couple of my take-aways first of technical terms, and later of general everyday language. I especially enjoyed the website https://itconnect.uw.edu/work/inclusive-language-guide/, which seems comprehensive and does provide alternative terminology along with explanations for why terms are problematic in the first place (and there were some terms on that list where I had absolutely no idea where they originated from!). I’m thinking about this in different categories:

A lot of terminology in academia is really ableist once you start thinking about it, for example a “(double-)blind review“. Instead of implying that blindness equals ignorance, speaking about an anonymous review, or one where the reviewers do not know whose article they are reviewing, would be much more to the point of what that term is actually trying to express. Also if we speak about someone who is “blind to something”, a better way to express that might be to talk about them being clueless or ignorant.

Similarly, the “dummy” in “dummy variable” comes from the historical use of “dummy” for someone who cannot speak, and who was then assumed to be less intelligent.

And do you sometimes feel like you need a “sanity check“? Or did you actually want to know whether your perception and/or reaction to something is appropriate, instead of implying that mental illness makes people wrong?

There is a lot of terminology that is racially insensitive and perpetuating stereotypes of black = bad and white = good, for example “black list” for deny lists (in contrast to a “white list” for the allow list), or a “black box” for a box where we don’t know what’s going on inside (in contrast to a white box, where it is transparent).

Speaking about “master/slave” is obviously problematic, and an easy fix is to speak about a main and secondary program/file.

While these are fairly obvious once we start thinking along those lines, there were others that I had no idea about. For example “no can do“: I thought that was just a fun way of saying “I cannot do it”. Turns out it is imitating Chinese Pidgin English and stems from a very racist time. Not something that I will use in the future!

Another example: I never thought about how a “mantra” has spiritual and religious importance to some people, so using it as abbreviation for “a phrase I often say to myself” is really not ok.

And then there are many more examples of phrases that I would use to show off my familiarity with English phrases, but that are related to the colonial history in the US, and that, on second thought, are actually not helpful for communication (especially in global English when communicating with people in a multicultural team). They are not actually literally expressing the essence of what I want to say, but rather assume some common understanding of what phrases and figures of speech mean (when my understanding was clearly not as good as it should have been in order for me to use these phrases!). Examples of that are “taking the cake” (which comes from pre-Civil War show competitions of enslaved people!!), or even “brown-bag lunches“, where it would be so much better to talk about “bring your own food” meetings at lunchtime, for example, instead of evoking the association of brown paper bags to determine whose skin colour is on the lighter or darker side of that.

This is a field that I am very much aware of and that I’m often calling people out on: “man hours” could very easily be “person hours” or “engineer hours”, a “chairman” is a “chair person”, “manning” a work station could just be “working”, “staffing”, or “taking care of” it. Just yesterday someone was talking about “mankind”, and I shouted “humankind”.

Another term that I saw on a list of things to avoid (which I can’t find again now) is “grooming”, as in “backlog grooming”, because it might evoke not just brushing a dog’s fur or clipping its nails (as it does to me), but also grooming that predators do to children. “Taking care of”, “cleaning up”, … there are many alternative that don’t potentially evoke negative reactions!

Another thing I wasn’t really aware of before is how often unnecessarily violent language is being used. For example someone might talk about how they are “killing it“, when saying that they are doing a good job, or exceeding expectations, is expressing the same sentiment in a more precise way, evoking less of a strong-man macho culture.

Or think about “aborting” or “terminating” a child process. Is it really necessary to evoke the imagery and emotions related to abortion, when you could just as easily cancel, stop, end, force quit a process?

This was a very interesting excursion into the world of inclusive language for me, and I am much more aware of what I (and others) say than I was before. But what next? How to share this knowledge and awareness without calling people out in a way that just makes them defensive and doesn’t actually get them to think? Yesterday in a workshop, someone was talking about how someone else was “blind to something”. I echoed back what they said, using clueless and ignorant as synonyms, and they took on that suggestion and seemed happy with it. Maybe, since the workshop was on microaggressions, that was enough to make them and the other participants notice and think about how they equated “blind” with “ignorant”. Maybe it also wasn’t. But then how big a deal do we want to make out of language in the moment, potentially distracting from and derailing a conversation that focusses on other, equally important issues? My personal strategy is to circle back to these things privately with the person who said these things, but then that also means that I did accept the situation, did not show solidarity with people who might have perceived the situation as hostile and/or aggressive, and I also did not include everyone in the learning opportunity and potentially intresting conversation. And I’m still figuring out what the best balance is. What are your thoughts?

I want to give you a quick summary of the super useful article “Improving Students’ Learning With Effective Learning Techniques: Promising Directions From Cognitive and Educational Psychology” by Dunlosky et al. (2013). A lot of what I write about on here is about how we can improve our own teaching, but another really important aspect is helping students to develop the skills they need to become successful and independent learners. This can be achieved either by explicitly teaching them study techniques, or by building lessons in ways that use those techniques (although I think that even then it would be useful to make the techniques and why they were chosen explicit).

In the article, Dunlosky et al. (2013) suggest one possible lesson plan that combines several of the techniques they recommend: Starting a new topic with a practice test and feedback on the most important points learned before, practising exercises on the current topic mixed with “older” content, picking up or referring back to old ideas repeatedly. Also, asking students to connect new content with prior knowledge by asking how the new information fits with what they already know and if they can explain it.

So what are the techniques we should be using and teaching our students? Out of the 10 techniques reviewed in the article, two are high impact, three are moderate impact, and the rest have low impact (even though some of those are the ones most often used by students), and I am presenting them in that order (and you might recognise them from the suggested lesson plan — surprise!).

One of the two most useful learning techniques, according to Dunlosky et al. (2013), is practice testing: either self-testing of to-be-learned material, or doing really low-stakes (or even no-stakes) tests in class.

For self-testing, this can mean different things, like learning vocabulary using (electronic) flashcards. When I was learning Norwegian, I practised a lot using the App Anki and self-written cards with vocabulary or sentences I wanted to know, now I use Duolingo regularly (616 day streak today, wohoo!). But it could also mean doing additional exercises, either provided with the teaching materials, or even seeking out or coming up with additional questions. For my exams in oceanography, as a student I spent a lot of time (mostly sleepless nights though) before the exam trying to imagine what I might be asked, and how I would answer.

I wrote about the importance of assessment practices and how “testing drives learning” previously, but here the important point is really that the students are ideally using this as a learning technique themselves.

The second high impact practice is distributed practice: not cramming everything the night before an exam, but spreading practice out over as long a period as possible, and come back to material repeatedly over time. This is not how we typically teach, nor how textbooks present materials (usually one topic is presented in one chapter, together with all exercises or practice problems that go with that topic), so it is not a learning technique that students are necessarily familiar with.

Distributed practice can be “encouraged” (enforced?) by frequent low-stakes testing in class. It is also built into the apps I mentioned above: Flashcards or practice problems that were answered wrong will come up again after a little while, and then, if you answered correctly, again and again with longer intervals in between. If you answered wrong, they’ll probably pop up even more often. And, of course, it is something that we can plan for and can encourage our students to plan for — ideally combined with an explanation and maybe some data for why this is a really good idea.

One moderate impact practice that I like a lot is interleaved practice: mixing different types of problems or different topics during a practice session. Interestingly, results during those practice sessions are worse than when the same types of problems or topics are practised grouped together. But when tested later, interleaved practice is a lot more efficient, likely because in interleaved practice, students learn to figure out which way to solve a problem is required for which type of problem. Whereas in blocked practice, it is very easy to just numbly apply a procedure over and over again without actually thinking about why it is the appropriate one for a specific case. Which is what I am currently experiencing with my Swedish classes, now that I’m thinking about it…

But, a second moderate impact practice could help in these cases: elaborative interrogation. There, we would do exactly what I describe above that I don’t do in Swedish classes: Asking myself why I am applying a rule in one situation but not in another, why a pattern shows up here and not there, and coming up with explanations. This is very easy to implement actually.

But it is not so easy to instruct as a technique, when we don’t want to prescribe the kinds of questions students should ask themselves, but want them to generate the questions themselves, and then answer them. How do we tell them at what level of abstraction or difficulty they should aim? If we give prompts, then how many? Maybe this is something we can / need to model explicitly?

Another moderate impact practice is self-explanation, where we explicitly connect new information with what we know already, explore how information fits together and which parts are actually new and/or surprising to us and why, or explain rules we come across. This is really useful for far-transfer later on.

We can prompt self-explanation on a very abstract level, giving general instructions like “what is the new information in this paragraph?”, or on a much more concrete level like “why are you applying this rule rather than that one?”.

The most efficient way to use self-explanation is to do it right in the learning process. But doing it retrospectively is still better than not doing it. And it is important for learning that we don’t have access to explanations, but find them ourselves (this makes me think of people that always bring out their smartphone and google the answer to an intriguing question, instead of engaging in the back-of-the-envelope fun).

And now we’ve reached low impact practice no 1: summarization. Writing summaries of the content we are trying to learn, that’s something I do a lot, for example just now when writing this blog post (but I don’t rely on remembering what I’m writing; I google things on my own blog. So maybe that’s not the same thing?).

Summarising, i.e. rephrasing the important points in one’s own words, is more useful that just selecting the most important content and then copying it word by word.

Another low impact, yet highly popular, practice is highlighting and underlining. I’ve never understood why people do that, I’ve always written my own summaries and found that a lot more useful. But reasons why people might do it is because it’s quick and looks like someone has done some work with a text, even though it isn’t more beneficial than just reading a text. But the part about looking like work has been done might give students false confidence in how much work they have actually done, and hence how much they have learned.

The “keyword mnemonic” low impact practice is about “building donkey bridges” as we would say in German — finding ways to remember more complex things by memorizing something simple, for example mental images or word sequences. I do that for example to remember the difference between refraction and diffraction, or the order of the planets in the solar system. But apparently it’s not a very useful technique at scale.

Another low impact practice related to mental images: creating mental imagery while reading or listening to texts. This can be helpful, and interestingly enough, the mental image is more useful than actually drawing it out!

And lastly: rereading. This is what students do A LOT in preparation for exams; reading old material again and again. This is a lot less efficient than the high- and moderate impact practices described above!

So what can we do with this information? As described in the beginning, we can include the higher-impact practices in our planning so students benefit from them without necessarily knowing that it is happening. But then we can also make those techniques explicit when we are using them, and encourage students explicitly to use them in their own studying. And we can point out that highlighting and rereading, for example, might feel like studying, but are much less efficient than those other techniques.

Dunlosky, J., Rawson, K. A., Marsh, E. J., Nathan, M. J., & Willingham, D. T. (2013). Improving students’ learning with effective learning techniques: Promising directions from cognitive and educational psychology. Psychological Science in the Public interest, 14(1), 4-58.

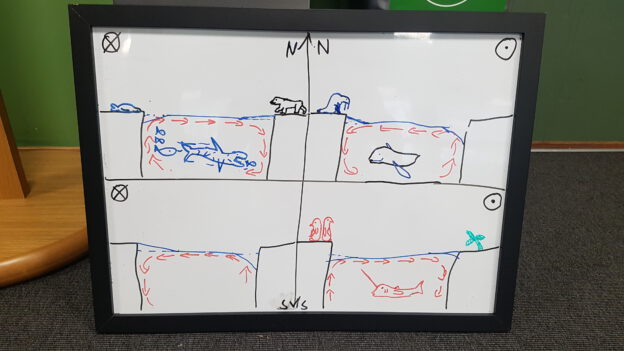

What a lovely Birthday gift (and seriously impressively quick turn-around times at TOS Oceanography!): Kjersti‘s & my article “Collaborative Sketching to Support Sensemaking: If You Can Sketch It, You Can Explain It” (Daae & Glessmer, 2022) has just come out today!

In it, we describe Kjersti’s experiences with using portable whiteboards that students use to collaboratively draw on in order to make sense out of new concepts or generate hypotheses for outcomes of experiments. It’s a really neat practice, you should check out our article and consider it for your own classes!

Kjersti also wrote a supplemental material to the article with a lot of details how exactly she implements the whiteboards and how she formulates the tasks (find it here).

Daae, K., and M.S. Glessmer. 2022. Collaborative sketching to support sensemaking: If you can sketch it, you can explain it. Oceanography, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2022.208.

Ha, I was so keen on getting to my morning swim that I scared one of the ducks so it didn’t just swim away (like the other one), but took flight for a meter or so, before it plopped back down into the water! Can you see it in the waves?

This one is for you @manelriveracamacho: an interference checkerboard pattern in capillary waves! And at the same time a really interesting case of total reflection: the whole green-yellow-ish part in the foreground is where we look directly at the slope of one side of a wave, and can look into the water because the angle is steep enough. For the whole blue area, including the one side of the capillary waves in the yellow-green-ish area, the angle is smaller, and in fact so small that we can’t look into the water any more, but instead see the reflection of the sky!

After spending a good chunk of yesterday afternoon transferring #WaveWatching pictures from my Instagram into a blog post here, and wondering why I did not bother to write better captions for all the cool pics I’ve posted, I thought I’d go back to my roots and start with, at and for my blog. And if I transfer stuff to Instagram later — even better!

So since I have the time and enjoy this stuff: Here are this morning’s pictures!

I really enjoy morning swims, especially when the sun is still low(-ish)! Here the sun’s reflection nicely highlights a group of capillary waves travelling away from us (probably caused by me moving in the water). One really interesting thing about capillary waves is that they behave differently from “normal”, longer waves: the shorter the wavelength in a capillary wave, the faster it travels! That’s why we see the one large wavelength-large amplitude wave on which the sun spot sits, and in front of it several parallel waves that are progressively getting smaller and with shorter wavelengths. Capillary waves, in contrast to “normal” waves, aren’t driven by gravity as the restoring force, but by surface tension. That’s why they are only a few cm long at max. I really enjoy how they always look so neat and tidy on top of a much more messy wind-driven wave field!

A couple of days ago, I commented on how the ripples on the sea bed were much more pronounced on a more windy day. Same thing today: Look at how they are several cm high in about maybe 70 cm water depth!

One thing this picture shows really nicely is also the problem that comes with interpreting these kinds of pictures: We see (at least!) three different pattern at once: 1) The waves on the water surface that show up as the reflection of the sky the shallower the angle we are looking at the water surface at is (but that, on the other wave slope don’t show up and let us look into the sea). Thanks, total internal reflection! 2) The light pattern on the sea floor where the sun is focussed and defocussed due to the shape of the sea surface that acts as a lens: rippling caustics. 3) The actual shape of the sea floor, the sand ripples

This is my new morning bath spot, and I have to say that I love it! First, it’s at the end of a 500m pier, which is awesome in itself for any wave watcher. Then, there are pigeon hole type shelves so my stuff stays put and doesn’t get blown into the sea. And then nice and clean and sturdy metal staircases leading into the water that is bio-free enough to see where you are stepping. And already after a week, a community of morning bathers who recognize me and comment about the weather and how morning baths are the best start into the day. I did not think that there could be another place as awesome as Seebar in Kiel, but I have to say that for as long as I can’t be in Kiel, this is a worthy replacement!

What I enjoy most about swimming is the change in perspective, and being able to look at waves from really close up. Aren’t the shapes just amazing? And I am so fascinated by how everything about water changes depending on the angle I’m looking at it (so whether I can look into the water or just see reflections of the sky), and also which direction I’m looking at relative to where the sun is (so whether there is sun glint), where the open sky is (so what colour the surface appears to be), where the wind is coming from (huuuugely important for what shape the waves seem to have, because you are either looking towards the steeper leading edge, potentially up breaking crests, or along the shallower back slope). And then, of course, all of this is ever changing, not two seconds will ever look exactly the same. It’s a wonder I get out of the water and stop taking pictures! (Well, maybe not that big of a wonder — it’s still not all that warm…….)

Hello, my name is Mirjam and I am addicted to #ColdWaterTherapy. It really makes me sooo happy every day!

Ok, and now on to some serious #WaveWatching. I was sitting on a deckchair on the beach, enjoying the sun and my coffee and talking to my parents on the phone, and then I spotted the wave pattern you might or might not be able to see (but it will become clear over the next couple of pictures).

See all the waves that come across Öresund? And then how something suddenly hapens at some distance from the beach, where some waves start travelling in a different direction, more parallel to the beach (so their crests perpendicular(ish) to the beach)? (Also, please admire some leftover sand ripples on the beach! Such a pretty contrast to the waves in the sea!)

If we look a little bit further downstream, we see that there is a sand bank maybe two meters from the water line, and that some waves are propagating around it on the landward side. The sandbank is a little bit submerged, which is why the wave crests are curving in that direction, too.

And here, a little more downwind, we have the two regimes: The wind waves, still being forced by the wind, running onto the sand bank (steepening up as the water gets shallower), and then the old wind waves running around the sand bank, now not in wind direction any more, and with a much smaller amplitude. Love how the wave crests are curving towards the shallower water on either side of the channel landwards of the sandbank!

So that was my Sunday morning wave watching! :)

I know, it’s not even Wednesday today, but I have to get all the pictures out that have accumulated since the last #WaveWatchingWednesday post on January 19th! Because these days, I go swimming in the sea every day so pictures are accumulating over on Instagram fast!

Since I’m sharing over four months in one post, I’ll break it down into several chapters and give you a little meta commentary in addition to the image captions, that are just what the captions on Instagram were when I posted the picture. Continue reading