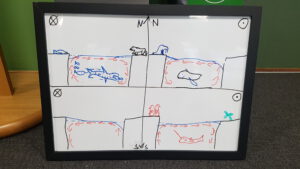

Article just published: Collaborative Sketching to Support Sensemaking: If You Can Sketch It, You Can Explain It

What a lovely Birthday gift (and seriously impressively quick turn-around times at TOS Oceanography!): Kjersti‘s & my article “Collaborative Sketching to Support Sensemaking: If You Can Sketch It, You Can Explain…