Thinking about “Universal Design for Learning”

Something that has been on my mind a lot lately is how to make learning situations welcoming and accessible to all students. A very obvious response is to the “accessible” side of things is to think about UDL: “Universal Design for Learning” (Brand et al., 2012). The general idea is that, instead of making accommodations when they are needed for individuals, there are four main principles that should be incorporated to make all parts of the learning process accessible to all learners:

- Multiple means of representation: This is about how students can take up our content, i.e. providing it in multiple formats so it can be accessed using different senses, and tailored to specific needs

- Multiple means of engagement: This is about how we motivate both initial and sustained student engagement with the content, providing multiple entry points, perspectives, etc.

- Multiple means for action and expression: This is about how students physically manipulate and communicate about the content via different options

- Multiple means of assessment: This is about how we test student understanding in different ways

When all these principles are met, learners with disabilities or with conditions potentially hindering their learning don’t have to disclose this information to the teacher, and courses don’t have to be adapted to specific students’ special needs ad hoc — they are already readily accessible. They also cater to students’ different circumstances and ways of thinking — maybe they are more used to certain ways of doing things than others for cultural reasons, or they simply have preferences (like listening to audiobooks over reading, so it can happen on a walk or driving to university).

There are many comprehensive checklists for UDL available online, if you would like to go that route. I personally found them a little overwhelming (which shows how important it is for me to actually think more about it!). So below, I share my thoughts on what UDL might mean in the context of teaching oceanography, following the Brand et al. (2012)’s structure. Note that I am just barely scratching the surface here, so watch this space for more and better information in the weeks to come!

1. Multiple Means of Representation

How can we present content in a way that it is accessible for all learners? Mostly by offering it in different formats so it can be taken up using different senses, as well as in ways that make it easily customizable to specific needs.

Perception (UDL 1)

This first point is really about how we make classical formats like graphics or texts accessible to everyone.

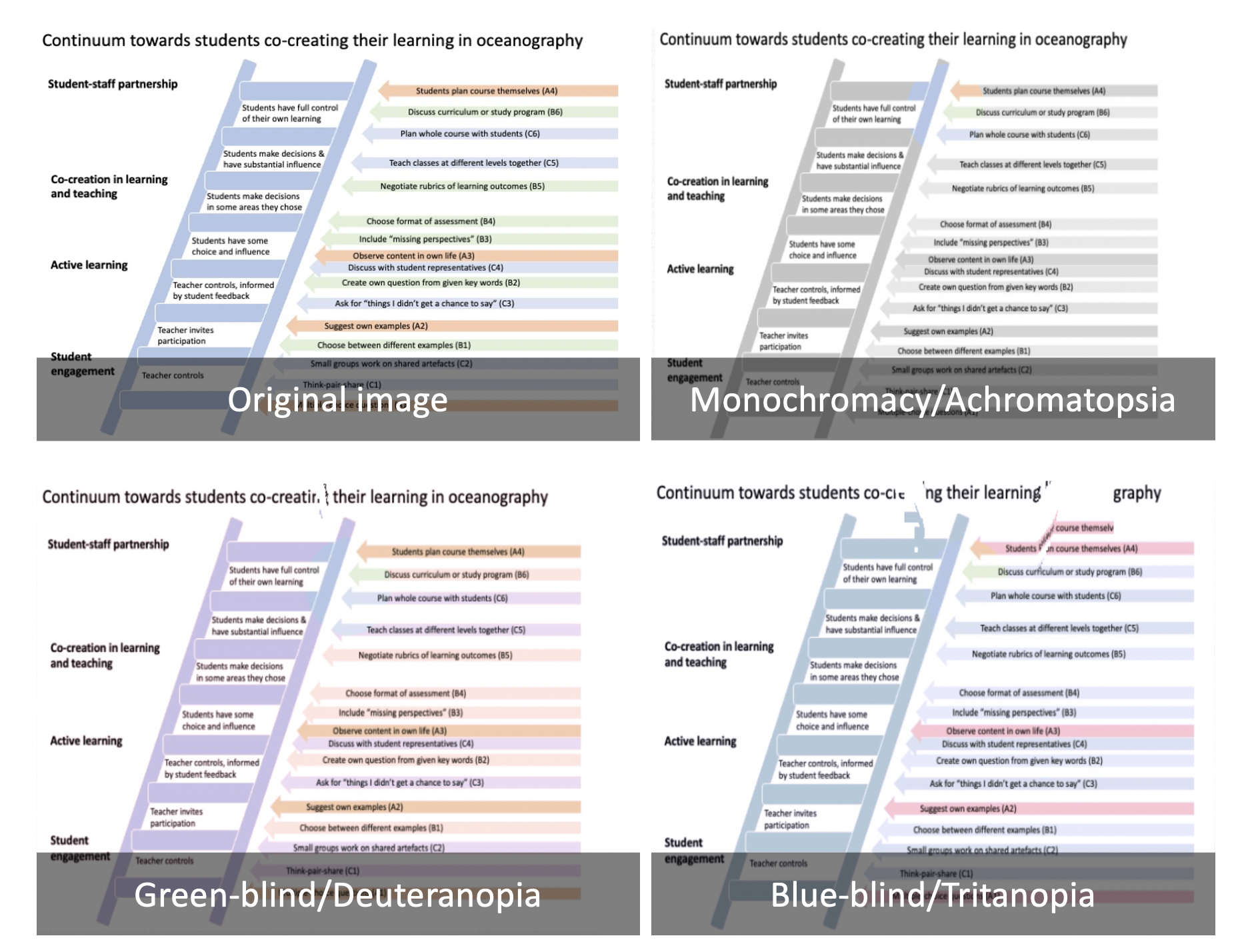

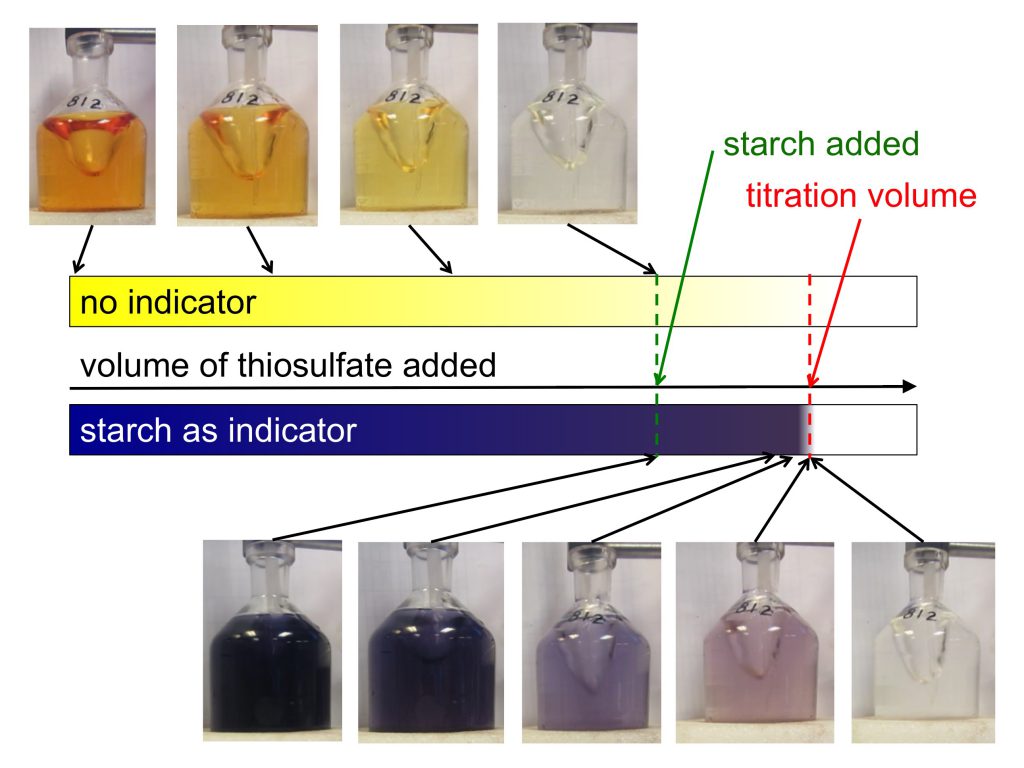

For example, if we are showing anything using colours (graphs! maps! photos! even text slides where we mark stuff using colours), we might look at it using grey scales, or run them through a colorblindness simulator (e.g. this one — see image below for an example of where I should really have done that), to see whether our pretty slide still conveys all the information that we see in it. And even when we’ve checked this, if we show a presentation in a physical meeting, can we share the slides so students can look at them on their devices in parallel so they can for example adjust sizes of images? And do we provide ALT texts so students can read/listen to a description of a graphic instead or in addition to of looking at it?

Our figure from a recent article (Glessmer & Daae, 2021) run through the color-blindness simulator at https://www.color-blindness.com/coblis-color-blindness-simulator/; top right corner of the ladder in each panel shows a circle with the original colors. Clearly should have done this check before submitting that image!

If we are working with texts, we might consider providing them digitally rather than on paper, so it’s possible to read them read them with help of either a screen magnifier or a screen reader, and in a format that lets people change fonts and easily feeds into a braille display, or to provide a recording along with the text.

For videos and audio files, it is really helpful when students can access them beforehand, so they can adjust speed, volume, … or automatically generate transcripts or subtitles if reading is their preferred option.

In general, a flipped-classroom approach seems like a good idea, because it gives students the chance to explore materials in whatever ways work best for them, and take their time doing it.

For in-person parts of a course, there are of course considerations related to whether the physical setting is hindering: is there a lot of background noise in the classroom, making it extra difficult for students that primarily rely on hearing? And of course much more general considerations: Is it possible to reach the room in a wheelchair, on crutches, without relying on eyesight?

But all of this is about “regular” lecture / seminar settings, what about labs and field courses?

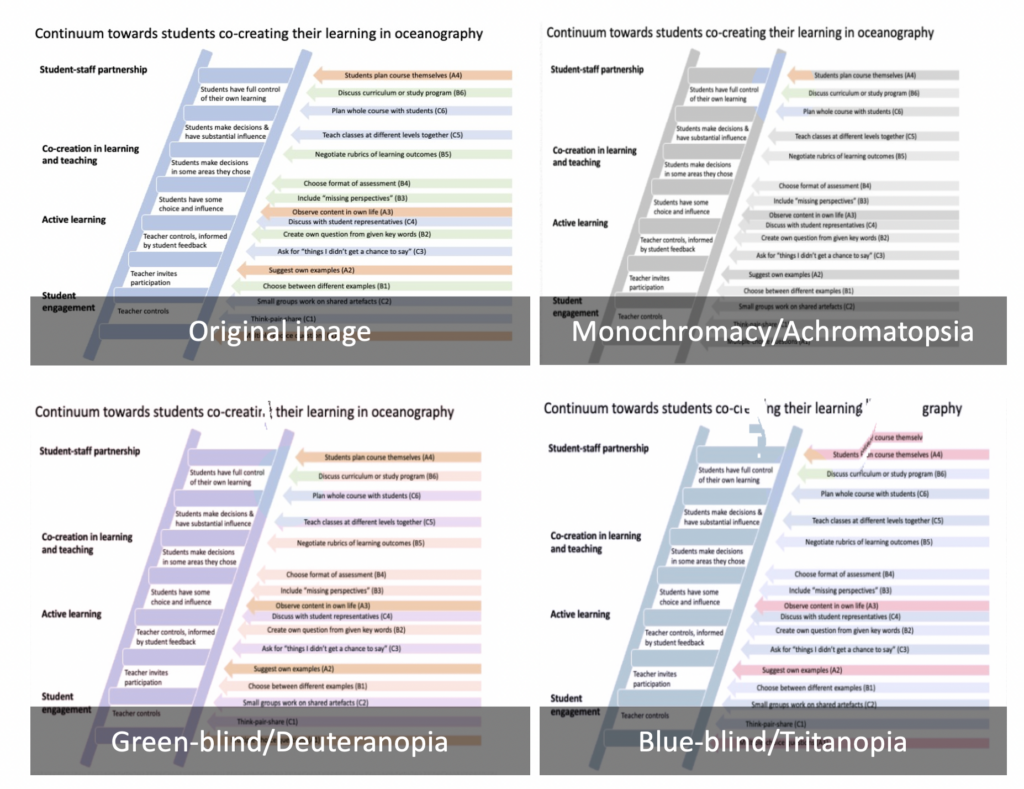

I did a quick search for UDL in physics labs, and found many helpful ideas. Holt et al. (2019) share ways to translate graphical data into tactile and or audible data. Not “just” converting digital displays on instruments (“just” in quotation marks, because not even that is commonly given), but also for example x-y plots, where the x-axis can be coded as time, and the y-axis as pitch of a beep. Wandy (2020) has a lot of useful tips and examples for “STEM for Students with Blindness and Visual Impairments”, for example an app that converts the colour change in a titration into beeps and vibrations. Titration is the method that we use to measure dissolved oxygen in seawater (see image below), so this could actually be very relevant in our context.

Winkler titration: Sketch + photos of the colour changes of just the sample, or a sample with an added starch solution, during titration. Note how it is a lot easier to find the titration volume when starch is added at the right moment!

Burgstahler (2008) provides a ton of good advice on “making science labs accessible to students with disabilities“, like for example providing extended eyepieces for microscopes so students sitting in a wheelchair can also use the equipment, or replacing glass with plastic, where possible. My next step on my UDL journey will definitely be to go through the Burgstahler (2008) list in more detail! And especially focus on thinking about field courses and student cruises, on which not even all students might be currently allowed due to health and safety rules and regulations.

Language and symbols (UDL 2)

A second point to consider is about how we make language and symbols, that we might often take for granted, accessible.

When we introduce new terms or technical language or even symbols like Greek letters, providing students with ways to prepare and practice might be a good idea. For example by glossaries that we provide or that we give students time to create themselves, by supplementing new symbols with written-out explanations of what they mean, or showing depictions alongside the new terminology.

When I taught an “intro to oceanography” course in English in Norway, for example, I started writing a dictionary of technical terms. And going on a bit of a tangent here, I recently found a really nice website about using “global English”, where the authors make the point that although we are all communicating in English a lot of the time, we still all have different skill levels and make a lot of unfounded assumptions about other people, for example based on whether they speak the same dialect as we do.

Comprehension (UDL 3)

This is about providing the best possible conditions for students to engage with new ideas: activating prior knowledge (for example through methods like letting students put together an A-Z of their topic (but then allowing for something that is in written format as well as maybe a podcast or video), or creating concept maps (again — in a format that does not only rely on vision)), scaffolding instruction so that everything builds on a solid foundation brick by brick (e.g. by providing advanced organisers), and guiding through the process (e.g. using diaries or rubrics)

2. Multiple Means of Engagement

What captures & sustains one student’s interest might not be what works for all students. So in order for all students to interact with our content, it’s a good idea to offer them different ways to do it, that are all accepted and valued equally.

I would usually approach this by looking at both what is likely to help student motivation (along the lines of self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000; so making sure that students can feel connected to others, competent in conducting their tasks, and autonomous in their decisions) or expectancy-value theory (a really good starting point for reading on motivation is Torres-Ayala & Herman; 2012). Within these frameworks, I would then look at specific features of the course I am planning.

Recruiting student interest (UDL 4)

How can we recruit student interest?

First, we need to figure out what students are interested in, so a good start is to ask them about their associations with the topic and how it relates to their experiences and interest. Based on that, we can tailor our content or even offer different options that students can choose from.

We can also spark student interest by showing them that concepts from class are relevant in their everyday lives, for example by using coffee to talk about the hydrological cycle or oceanic mixing processes (see here), letting them do easy hands-on experiments at home (#KitchenOceanography) or sending them on hyper-local expeditions right outside their homes (#WaveWatching). Here we need to consider how accessible each of these are, too. In #KitchenOceanography, if we work with plastic containers, it is very easy to feel different temperatures, for example to investigate a temperature stratification. Since we are only using food colouring, tasting the salinity is an option. Even for #WaveWatching, there is a lot that can be discovered by listening to wind and waves (are they breaking? what’s their period? can we connect that to other sounds, like did we for example hear a ship go past earlier?) or even just feeling a ship or dock (or water around our ankles) move. If you think of Polynesian stick charts — those people could navigate from island to island just by feeling the waves!

It also helps to make sure class times are conductive to learning (if you have the choice, Monday morning at 8am might not be optimal, nor Friday afternoon at 5pm).

Sustaining effort and persistence (UDL 5)

Sparking student interest in the beginning is not enough, students need to stay engaged in the long run. For this, many of the same strategies work that sparked their interest in the first place, except we just keep enquiring about what students find interesting, how things relate to their lives, let them include missing perspectives. And we can offer different roles that people can take on, so they can experiment with different identities or pick the one that resonates with them the most (“battle of theories“, “writing summaries from different perspectives“).

We can also provide rubrics, advance organisers or checklists, so students know how far they have come and what is still to come, as well as “intermediate goals” where students can succeed and feel competent along the way.

In addition, creating engaging environments also includes opportunities to interact with others, both so students feel the “connectedness” referred to above, as well as generally having a supportive community around them.

Self-regulation (UDL 6)

Part of engaging is also to help students self-regulate their learning, by letting them practice working with checklists, (negotiated) rubrics, and let them set their own goals.

3. Multiple Means for Action and Expression

Some people can engage in discussions for hours on end, others might prefer written discussion forums or video essays. Some people might prefer to write on paper while others prefer to click or type. For many people, it is not even about preferences, but about what they are able to do. So offering multiple ways for action and expression makes it possible for everybody to engage.

Physical actions (UDL 7)

How are students physically interacting with our materials? Is it, for example, possible to either write by hand or type on a computer, or voice record? Can lab equipment be steered by a joystick as well as a keyboard or voice?

Burgstahler (2012) gives more useful pointers here, like for example making lab spaces safe by using plastic instead of glass, making sure there is no time pressure, including tactile models, and many more

Expressive skills and fluency (UDL 8)

This point is about giving students the choice of format, and not just how they do their homework, but also how they contribute in class or in small groups. I feel that is often forgotten with our focus on peer-instruction and discussions etc, and despite its obvious work place relevance: Not everybody might be able to participate in the same way! In addition to disabilities, maybe a student has social anxiety, or is shy, or prefers to think things through before speaking. So how can we make conversations more accessible?

For example, when asking for feedback, this can be done through many different methods. For example, in a “flashlight” you go around the room and everybody speaks, but people might feel put on the spot. In a “lightening storm in the chat“, people are less exposed, but have to type, or input into the computer in a different way. But in both cases, fairly spontaneous expression of opinions is required, so using something like “continue, start, stop” and giving people time to think might be a better option.

I also really like asking people for things they didn’t get the chance to say after a course, so no good ideas get lost just because someone was too shy or for other reasons did not react in the moment.

Executive functions (UDL 9)

This point is about students gaining an overview over all tasks that need to be performed, and then keeping the overview as they execute them. This means supporting them in goal setting and project planning as well as in using management tools like checklists or software.

4. Multiple Means of Assessment

Again, providing choice in methods and formats goes a long way. Since, according to constructive alignment, what students do as part of their assessment should be what they practised in class, I would like to refer to all of what I wrote above and not repeat too much of it here. So in a nutshell:

Methods (UDL 10.1)

Here again, giving students choices is super helpful, both in the methods (MCQ, oral examination, essay, what have you). Also it is good to make sure there is no time pressure and the location is conductive to thinking (maybe more quiet, or in the same classroom as the course was taught to help with situated learning, or at home/in the library where the students engaged with the content most.

Formats (UDL 10.2)

Making sure that there is choice in how students interact with the tasks (text-to-speech / speech-to-text, type, build a model, …).

Scope/range level (UDL 10.3)

If the final exam doesn’t count for 100% of the final grade, the pressure becomes less and it is also easier to have many different formats that accommodate different students in different ways contribute to the final grade. Negotiating the rubric and assessment in general seems like a very useful idea here.

Product and outcome (UDL 10.4)

Letting students create different types of outcomes (for example a blog post or tiktok instead of classical lab report) is motivating, lets them make something that might actually serve a purpose beyond assessment, and also accommodates different abilities.

Feedback (UDL 10.5)

Feedback can be reflection or self-assessment using the checklists and rubrics, peer-feedback (which has been shown many times to be as “good” as instructor feedback), or feedback by the instructor. It can happen for example in written form, in conversations, as checkmarks on a rubric.

What’s next?

Obviously, this is not a comprehensive list of things to consider and suggestions of how to fix them. A useful next step might be to apply all these considerations to a specific course I’m planning, and run my thoughts on that past someone who has thought about accessibility more, possibly through specific lenses like being hard of hearing or very shy or not a native speaker.

Writing this blog post, I noticed that I am very much missing the perspective that just because something is “accessible” to everyone (which it definitely should be!), it does not mean that everybody feels welcome enough to actually take part in it. So how can we make sure to create learning environments that are not “just accessible”, but also welcoming and safe*? One aspect is that we need to become aware of microaggressions and intervene appropriately, but there are so many more! But I need to do more research here, that’ll have to wait for a later blog post.

And one last rant, even though only marginally related to UDL: Did you know that when science and engineering meetings went online due to covid-19, “female attendance at virtual science and engineering meetings grew by as much as 253%, and gender queer scientist attendance jumped 700%” (Skiles et al., 2021), and that not being in the same space physically does not even hinder networking (Jack & Glover, 2021)? The ad-hoc change to virtual conferences did certainly not include enough considerations regarding accessibility etc, but we should make sure that we don’t just fall back to in-person meetings and forget all the positive contributions to diversity and inclusion of virtual conferences!

*”safe” being used here as meaning that people have “dignity safety” (i.e. are free from discrimination and humiliation), but that their “intellectual safety” remains challenged so they can learn (See for example Callen, 2016)

Brand, S. T., Favazza, A. E. & Dalton, E. M. (2012) Universal Design for Learning: A Blueprint for Success for All Learners, Kappa Delta Pi Record, 48:3, 134-139, DOI: 10.1080/00228958.2012.707506

Burgstahler, S. (2008). Making science labs accessible to students with disabilities. DO-IT, University of Washington.

Callan, E. (2016). Education in safe and unsafe spaces. Philosophical Inquiry in Education, 24(1), 64-78.

Holt, M., Gillen, D., Nandlall, S. D., Setter, K., Thorman, P., Kane, S. A., … & Supalo, C. (2019). Making physics courses accessible for blind students: Strategies for course administration, class meetings, and course materials. The Physics Teacher, 57(2), 94-98.

Jack, T. & Glover, A. (2021) Online conferencing in the midst of COVID-19: an “already existing experiment” in academic internationalization without air travel, Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 17:1, 293-307, DOI: 10.1080/15487733.2021.1946297

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American psychologist, 55(1), 68.

Skiles, M. et al, Nat. Sustain., 2021, DOI: 10.1038/s41893-021-00823-2

Torres-Ayala, A. T. & Herman, G. L. (2012). Motivating Learners: A Primer for Engineering Teaching Assistants American Society for Engineering Education

Wandy, Alexa. “STEM for Students with Blindness and Visual Impairments: Tenets of an Inclusive Classroom.” (2020).

How much of the work should the teacher vs the student do? Teaching as a dance, inspired by Joe Hoyle - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] learning in higher education”, occasionally giving inputs, for example on microaggressions or Universal Design for Learning. And, this morning, about dance as a metaphor for learning and […]

Reducing bias and discrimination in teaching: an annotated, incomplete - WORK IN PROGRESS! - list of references - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] Read more about my thoughts on UDL on my blog: https://mirjamglessmer.com/2022/01/31/thinking-about-universal-design-for-learning/ […]

Lund University "HT samtal" podcast on "teaching sensitive topics" - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] very brief discussion of “safe spaces”, with a quick mention of the distiction between dignity safety and intellectual safety. If we show students that we are prepared for discussing sensitive topics, that we have a plan, […]

Exploring the UDL 3.0 version, inspired by an episode on the Tea for Teaching podcast - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] to consider when designing teaching. Initially, I tried making sense of all the different facets by finding examples of what they could mean in practice. One book in particular, “reach everyone, teach everyone” by Tobin & Behling […]