This summer I had a fun little side project: I was co-supervising a Bachelor thesis in geography at Kiel University! Janina Dreeßen, with Katja Kuhwald as her main supervisor, did an excellent job, and I am presenting her work at the #FieldWorkFix conference today. If you can’t join later, here are my slides and what I’m planning to say. Enjoy!

Janina’s task was to create a learning opportunity on coastal protection for 16-year olds in a school setting, to run it with some students from her target group, and to do a preliminary evaluation of how it worked. And that’s what I want to present here (of course she also did a review of both the subject of coastal protection, and the literature on how students learn with digital media and on excursions, but that’s beyond the scope of this presentation).

The learning outcomes that Janina focussed on were

- to be able to name which coastal protection measures exist close to the students’ homes (i.e. on a specific part of the German Baltic Sea coast),

- to recognising those coastal protection measures “in the wild” and understand their functioning, and

- to explain why there are rules in place to protect dunes etc, and what the rules are.

Because of Covid-19 regulations in Germany this spring, we wanted to create something that could be done outside, and socially distant.

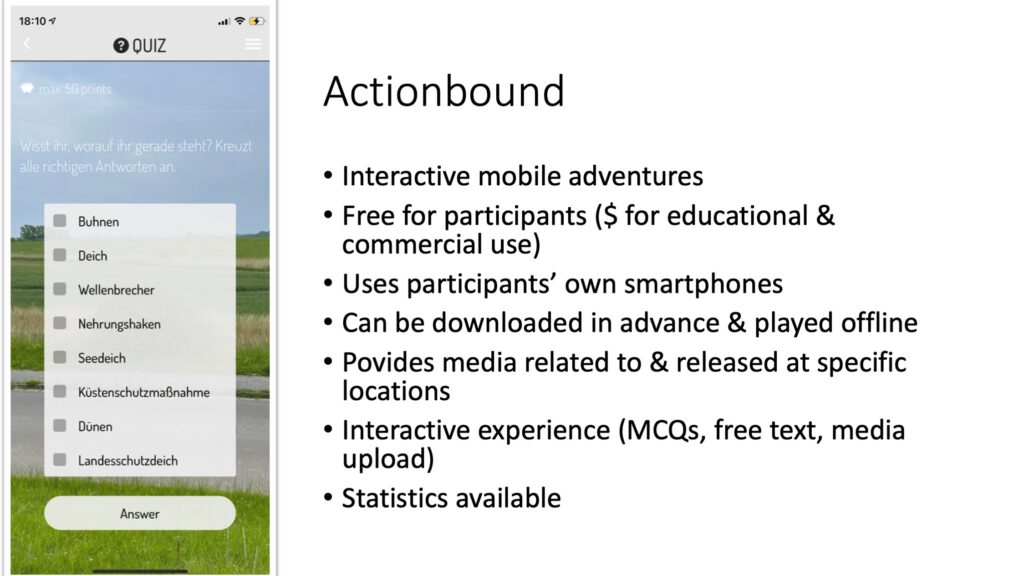

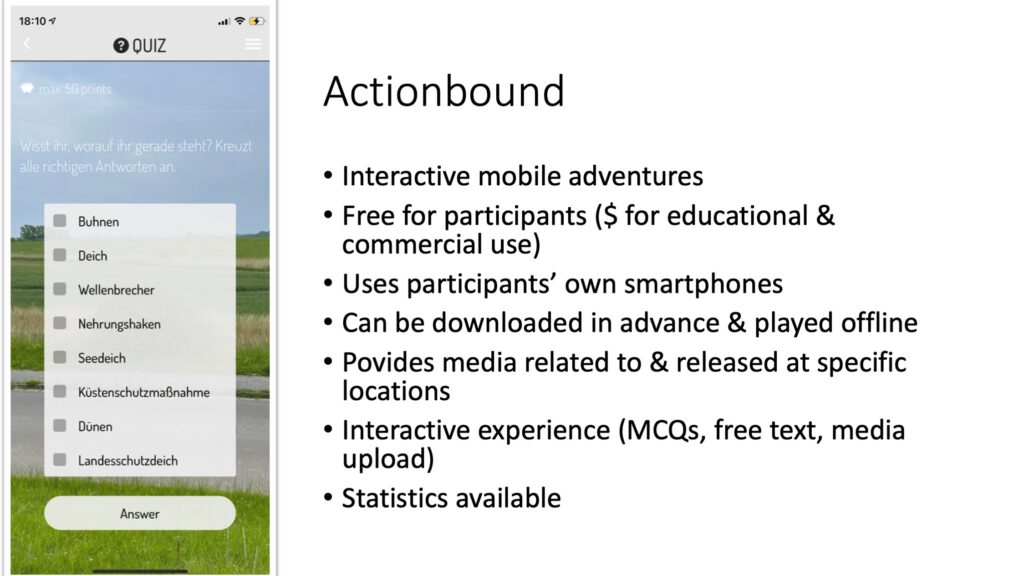

We decided to create a virtual scavenger hunt using the app Actionbound that provides the platform and an easy drag-and-drop interface to create interactive mobile adventures. Actionbound serves as a virtual guide to different locations, which you can navigate to following an arrow or looking at a map, and you can prescribe whether the mobile phone’s GPS actually has to show that a location has been reached (within a couple of meters) for the scavenger hunt to continue, or whether you trust your players to find it, or you can also allow to skip it.

Within the app, you can provide media related to, and released at, specific locations: Movies, sounds, pictures, texts; so there is a great potential to use this in teaching. Actionbound scavenger hunts are also interactive experiences, as it is possible to create quizzes using multiple-choice questions, ask for free text answers, or media uploads. All of these can be made compulsory (so you can’t continue the scavenger hunt unless you respond) or voluntary, so they can be skipped.

Actionbound runs on the participants’ own smartphones, and scavenger hunts can be downloaded in advance and played offline, if data usage is restricted or the network in the region might be a problem.

The person who creates a scavenger hunt is provided with usage statistics: How many people played, how long they played, what they answered, the files they uploaded, those kinds of things.

Playing a scavenger hunt using Actionbound is free for players. Creating scavenger hunts is free for private use (so great if you want to just test it!), but for educational or commercial use, you have to buy licenses. We were lucky as we could get a free educational license under the umbrella of GEO-Tag der Natur, which bought licenses and distributed them for free to people creating scavenger hunts to be played on the topic and within the timeframe of that larger project (no coincidence here, that’s my project and Janina’s idea was a perfect match for what we were looking for :-)).

The design of our scavenger hunt was guided by our interpretation of the self-determination theory by Deci and Ryan (e.g. 2000, but many more). This theory suggests that learning is optimal when it is intrinsically motivated, and that in order to feel intrinsic motivation, three basic needs have to be met: autonomy, competence and relatedness.

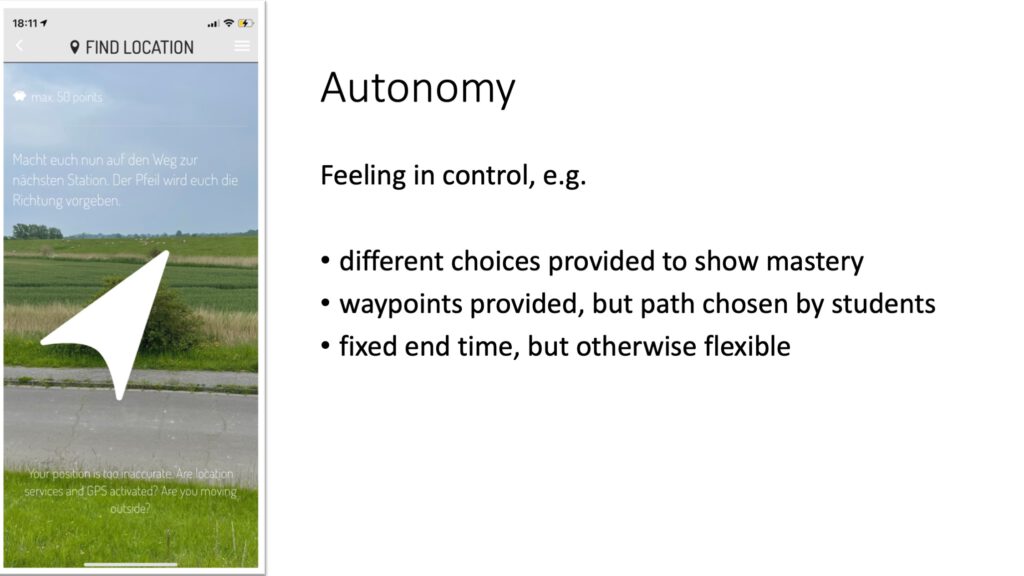

Autonomy means that we need to feel that we have control over our behaviour, that we have choices that we can make in whatever way we please. Obviously in a school setting, there is always going to be external constraints, but the more we can give students ownership over what is going on, the more likely they are to feel motivated.

For our scavenger hunt this means that, where possible, we provide different options for how tasks can be done (and I will give an example of that later).

We do want everybody to reach specific waypoints and look at different things along the way, but we give participants flexibility for how exactly they reach those waypoints (there is an obvious way, but they can also do detours on the way if they like), and how they organise their time. We do that for example by letting them know when they have reached the mid-way point and what type of larger tasks are still ahead of them, so they can estimate how much time they will need to get back to the starting point, and decide when and where they would like to take their breaks.

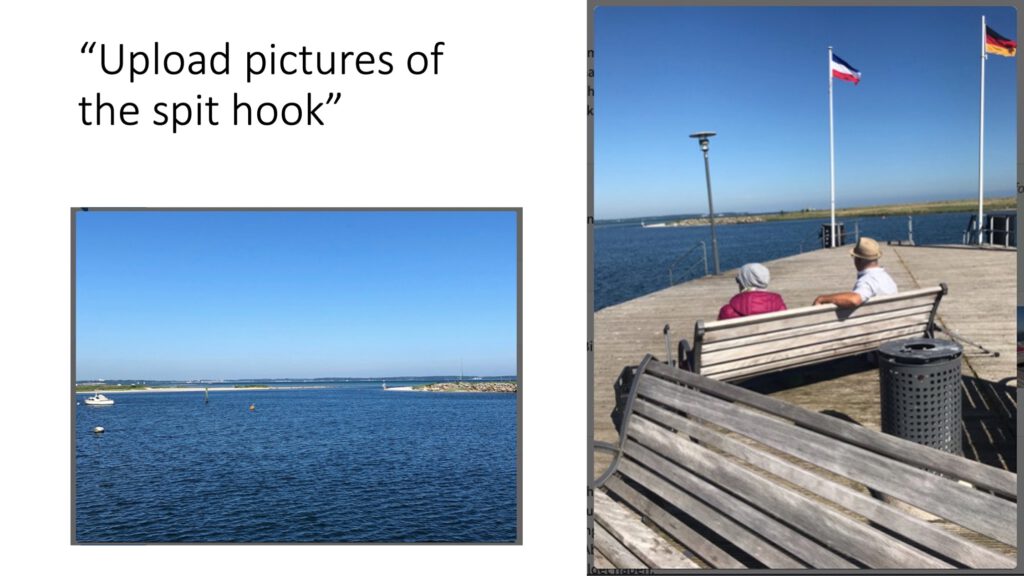

Below, you see a map of the area we were focussing on: We start out in location (1), then students head to stations 2 to 11, and then everybody meets up at station (12) in the end, to drive back to school together. On this tour, students see many features that are relevant to coastal protection, some of which you can probably spot from this satellite picture: We see for example the marina, the slip hook which contains a nature reserve, sand banks offshore off the coastline, a dyke, and groynes.

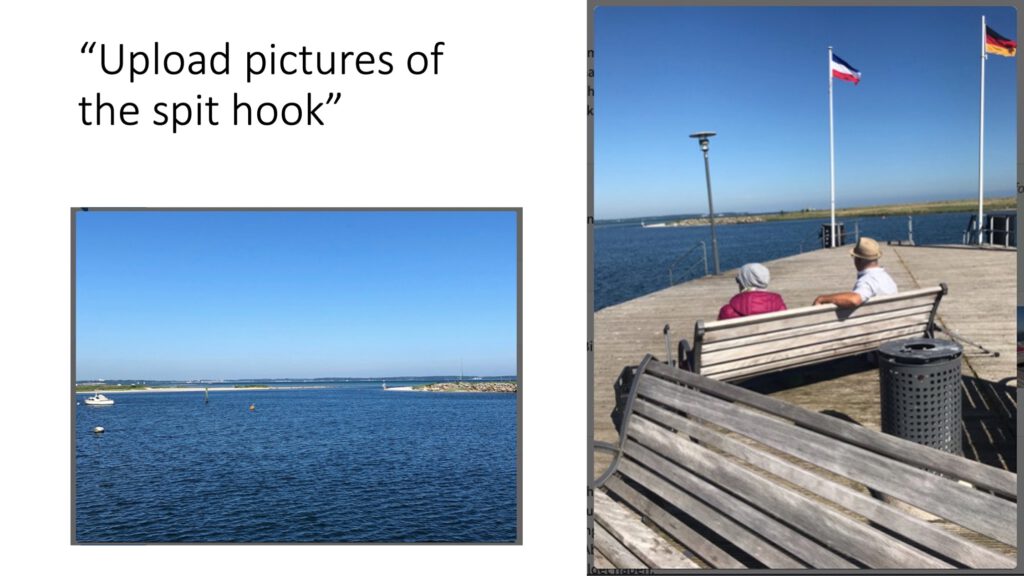

We do want to know whether students recognise relevant features along this tour that they’ve been introduced to earlier, so one task was for example to take and upload a picture of the “spit hook” — a term that they were likely not familiar with before and where they had to make the transfer from the map above to the feature you see in the pictures below. It was visible on all pictures students submitted, although better on some than on others.

Back to basic needs that need to be fulfilled in order to feel intrinsic motivation! The second basic need, the feeling of connection, we try to address by letting students work in small groups of 2 to 4. Within those groups, we foster a sense of belonging by starting the scavenger hunt off by asking them about their personal experience with extreme(-ish) events.

This, for example, shows a relatively common (as in about once a year) event in Kiel, the next bigger city to where this scavenger hunt is located, that students doing this tour are likely familiar with: Storm surges in the Baltic Sea often lead to roads close to the water being closed and flooded, and waves breaking over the sea walls. Damages to sea walls can regularly be seen (also because it takes years before they are being repaired), and booms to close roads off with with “road closed due to flooding”-signs are permanently installed, so students should have some personal experiences and prior knowledge that can be activated. Talking about personal experiences and sharing stories about them is a good way bond with others.

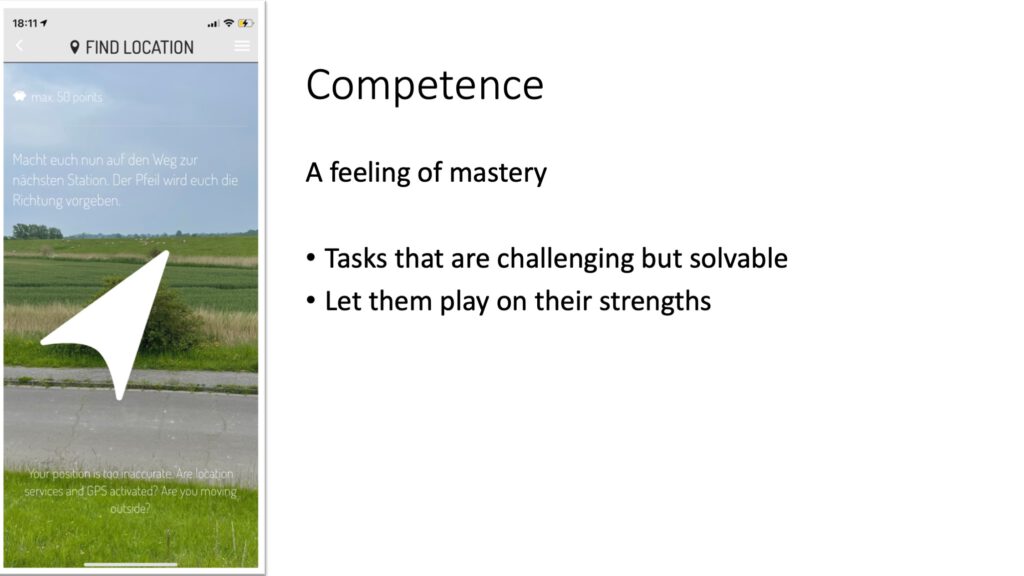

The third basic need that must be fulfilled is a feeling of mastery, which we tried to ensure both by scaffolding our tasks and by making sure that students could make choices that would allow them to show their strengths.

For example, the last task of our scavenger hunt was to create a movie about a coastal protection measure of their choice, in whatever format they chose. They were given this task at the farthest point out, so they could walk back past all the coastal protection measures they had seen on their way out, contemplating the task, and then use free time towards the end to implement it.

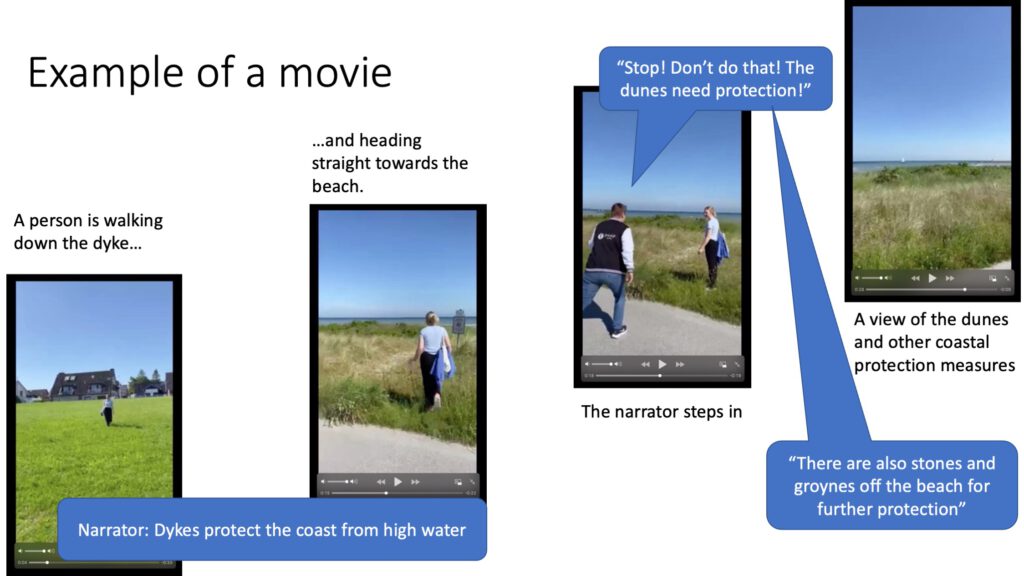

I expected students would submit something that looks like what we show here (although that’s my incredibly adorable and smart three year old niece and not a 16 year old student): building structures on the sandy beach, maybe discussing the design criteria behind them, and then maybe making a large wave to show how it breaks (or doesn’t break) the structure.

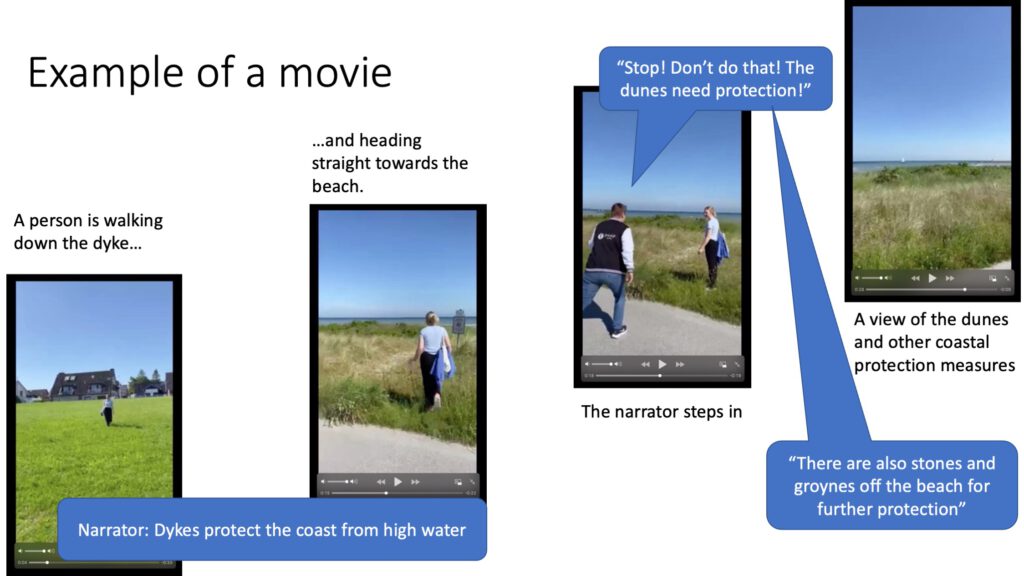

Here is one example of a movie that was uploaded (and other examples include someone sitting on a bench, talking about coastal protection in a story-telling sort of way), that was clearly thoroughly thought-through and produced: The movie shows a person walking down a dyke towards the sea. As she is walking, a narrator talks about how dykes protect settlements from storm surges. The camera follows the person walking down the dyke as she crosses a street and starts stepping on the dunes, where the narrator (who is now also visible on camera) steps in and tells her to stop, and explains how there are rules in place to protect the dunes. He then also points out other coastal protection measures that are visible in the distance.

So now we are coming to our conclusions. Throughout this process, and testing this scavenger hunt on a 10th grade geography class, what did we learn?

Generally, things worked really well. Being able to deliver inputs at specific locations without students following a guide around gave them a feeling of autonomy which they seemed to enjoy, and we were positively surprised by the quality of most of the artefacts we collected via the app. Despite (or maybe even because of) it’s game-like appearance, Actionbound turned out to be well suited for use in a school context, although the effort of creating a scavenge hunt is not inconsiderable. In our case, we created a scavenger hunt that can be played by many different school classes over months or even years, and the effort needed to set something like this up might be more realistic than if it is just done for use with one single class.

Using self-determination theory to guide development was also useful for us, because it reminded us to include elements beyond the classical tasks of “read this, then answer the question to show us that you understood what you read”. Including elements of gamification made it fun and memorable, but did hopefully not distract from learning.

But another thing we learned (which we had also been advised before, but I guess this is something everybody needs to learn for themselves): test, test, and test again! It is frustrating if, for example, “dog” is the expected and accepted answer to the question of who is not allowed in the dunes, and “dogs” then isn’t counted as correct, or even looses you points. Those kind of things we only caught when testing with the school class, but would ideally have caught earlier.

And then we were very lucky with the weather — this might not have been fun if it hadn’t been warm and sunny, and we did not have a backup plan!

One thing I would try and implement more next time is to have students really do something at the location they are at — not just observe, but actually either collect something that they bring home to analyse later, or have them work on an artefact that stays in this location and that other groups can build on (giant sandcastle? wall painting? …?). Because now for us it was great that students could see the coastal protection measures “in the wild”, to scale, interacting with the ocean (albeit on a calm day), but I would like to strengthen that connection with the actual physical location even further in the future.

One last thought: I would really like to do a similar thing as co-creation in the future, where students design scavenger hunts to teach other students about a topic they first did some research on themselves. That would a) be a great way to document their own learning (instead of e.g. writing a report), and b) likely lead to scavenger hunts that are even better tailored to that specific target group, and even more fun to do. Actionbound has that option already implemented, and I think that could be great!

But that’s for another time.

Thanks, Janina and Katja, for this fun project! :)