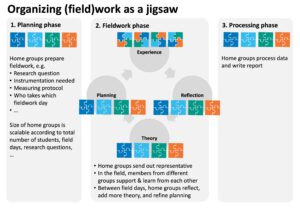

Structuring fieldwork as a jigsaw to increase student responsibility in, and ownership of, their projects

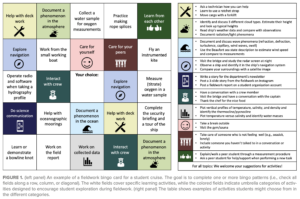

I am a huge fan of Kjersti‘s excellent teaching, it is always so inspiring! She, together with Hans-Christian, developed a jigsaw method to structure preparation for a student cruise, the…