Currently reading: “Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning” by Lang (2021)

On the “tea for teaching” podcast episode on trauma-aware pedagogy that I wrote about here, the book by Lang (2021) on “Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning” was recommended. It sounded so interesting that I decided I had to read it*, and I am glad I did!

The book is full of small (really, really small!) tweaks that individually, and even more so collectively, can improve teaching. But the implicit expectation isn’t to change everything at once, which is obviously not really realistic anyway. Instead, the reader is asked to think about the class tomorrow morning (is there one small change for five of the 90 or so minutes I’m teaching? How about if I open up in a new and motivating way?), next semester (can I, for example, change a whole session, or the language on the syllabus?), and then your whole teaching career (if I’m going to do this for another couple of decades, where do I want to develop to?).

What I also really like about this book is how all the information is presented on several levels in parallel: In really concrete “small teaching quick tips”, which are also presented in form of their underlying principles, and in a more comprehensive explanation that brings in the learning science that they were derived from. For me, this led to fun, non-linear reading: For some chapters, I wanted to know the whole background and then see what follows from it, for others I just checked the quick teaching tips and then sometimes dove back into the background to see what they were built on.

I don’t want to give away all the teaching tips here or summarise the whole book, but I am going to mention a couple of things that stood out to me.

In the chapter on belonging, which was the first one I read (again, love the modular way the book is structured, that makes it super easy to jump back and forth), the focus is on one big obstacle to belonging: a fixed mindset and doubts about whether one is good enough to actually be at university. Things we can do to help students feel like they cognitively belong are for example

Asset-spotlighting: an activity to focus on what is good, not what is lacking: Inviting students to introduce themselves on notecards to the teacher not just with the usual information, but also with something they are especially good at, proud of, or interested in, and the promise to try and find a way to include it into the class. How inspiring is this! I can totally see how that will influence the teacher and the way they meet the students, but also the students’ mindset because they are reminded of what they bring to the course that might help them succeed, and how the course relates to other interests they have. Especially if the teacher actually follows through and includes (some of) the topics they mentioned to actually make the course relevant to students’ skills and interests!

Name good work: it’s as easy as the name suggests. Point out when someone did really well, either in front of the class, or in short messages afterwards. This does not have to be “just” about deliverables, but could also about leading a group discussion or any other form of participation. Pointing out that someone contributed is also pointing out that they are in the right place. One really important tip here is to keep a list of who you’ve praised & make sure that over the course of the semester, everybody receives praise at least once (based on something good they do, obviously, but everybody does at least one good thing during a semester!).

Normalize help-seeking behaviour: For example by including a statement on syllabus to let someone know if there are problems with, for example, food and housing: Those things don’t exclude you from belonging at university! This is something that I have always taken for granted, but that really isn’t granted at all, not even in Sweden. So important to be reminded of that! And of course help can and should be sought for other issues, too, like mental health, or study skills, or anything else.

One tiny teaching tip mentioned in the book is to not call on anyone to answer a question before at least five hands are raised. What I’ve been thinking about since: then how do you decide who gets to speak? Which is really interesting to reflect on. How do I usually decide who gets to speak in what order? Is it really only about how quick people are to indicate that they want to say something?

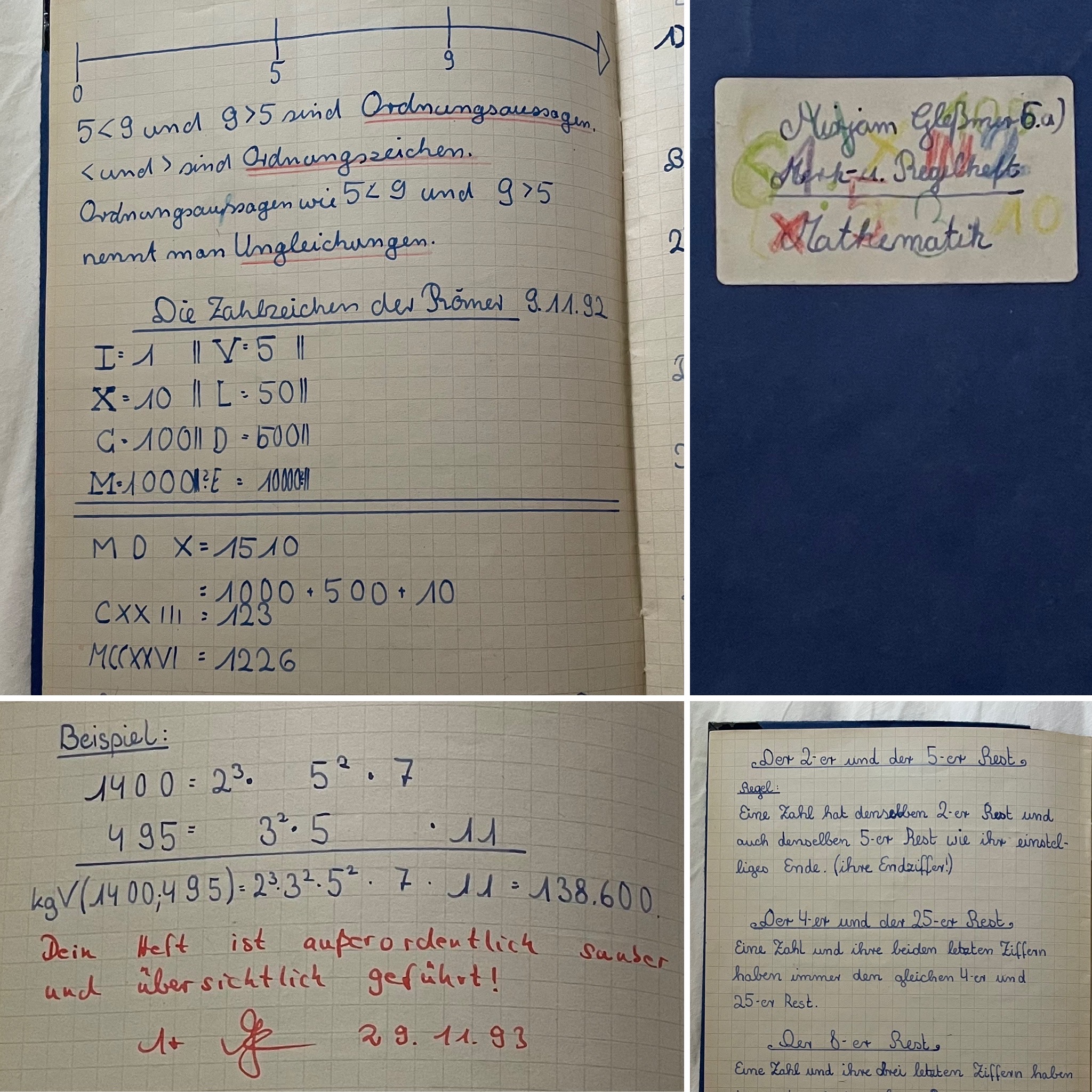

One thing that stood out to me in the chapter on “connecting” is the connection notebook. I have been keeping those all my life but have not explicitly included them in my teaching so far. In fifth grade math, we had a “Merk- und Regelheft” (Something like “rules & other stuff to remember”), a special notebook that we kept for the purpose of writing down rules that we learned (in our best handwriting, no less!), and that I actually kept to this day (see pic at the top of the blog post. This is something that I wrote in 1992, 30 years ago!). Later, during my studies, I was given a “Schlaues Buch” (“clever book”) by my friend: again a special, pretty notebook to keep all kinds of notes related to my thesis work. And I have been keeping lab books ever since, even now that I have not worked in a lab for a really long time, where I keep notes of things I read, presentations I see, thoughts I have, plans I make, brainstorming, sketches, everything. It’s still a physical notebook that travels with me everywhere! Long story short: based on personal experience, I think it is super useful to keep notes on all kinds of things in one place. In order to find them quickly, but also, as is stressed in the book, to discover new connections. And I love the suggestions of how to use this explicitly in teaching, by making time for students to take notes on new things they learned, thoughts they had, connections they made, and by explicitly prompting them to explain where they recognise concepts from the course outside of the classroom in real life, on TV, in another class. But this is something that I was taught at a young age, and which was then prompted again by a role model. So the advice to “build into your teaching approach frequent opportunities for students to come up with their own examples, analogies, and reasons.” is really one after my own heart! It also relates very much to the advice given in the chapter on motivation: your favourite subject is very unlikely to become all of your students’ favourite subject as well. But you can make them start noticing things, wondering what is going on, creating connections with what they see around them!

All these points are just a tiny fraction of all the great advice collected in the book. I totally recommend you read it!

*I requested and received a free digital evaluation copy of the book, which I am grateful for. However, this is not a sponsored post, and I am writing this without having been prompted or receiving any compensation for it.

Lang, J. M. (2021). Small teaching: Everyday lessons from the science of learning. John Wiley & Sons