How to show my favorite oceanographic process in class, and why.

As I mentioned in this post, I have used double-diffusive mixing extensively in my teaching. For several reasons: Firstly, I think that the process is just really cool (watch the movie in this post and tell me that it isn’t!!!) and that the experiments are neat and that everybody will surely be as excited about them as I am. Secondly, because it shows that understanding of small processes can be really important in order to understand the whole eco- and even climate system. And thirdly, because it helps to demonstrate a way of thinking about oceanography.

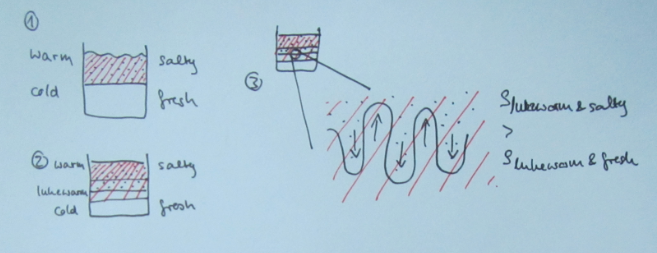

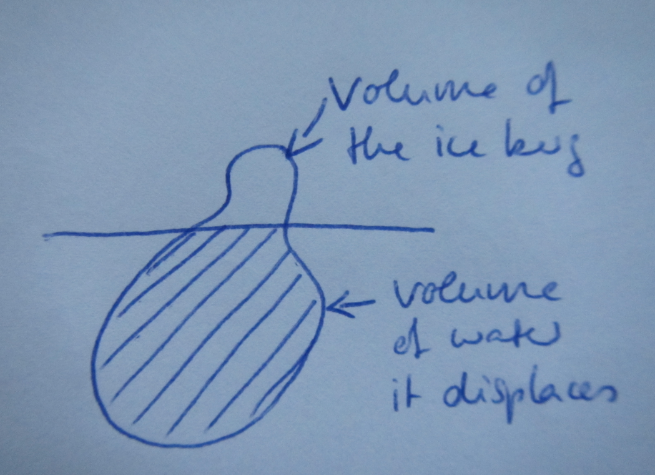

When I introduce salt fingering, I talk students through the process in very small steps. It goes something like this (Numbering is referring to the sketch below):

1) Initially, you have a stratification where warm and salty overlies cold and fresh water. This stratification is stable in density (meaning the influence of the temperature stratification on density outweighs that of the salinity stratification).

2) Since molecular diffusion of temperature is about a factor 100 faster than that of salinity (we will talk about why that is in a later blog post), the interface in salinity is initially basically unchanged, whereas a temperature exchange is happening across that interface, and a layer of medium temperature is forming.

3) At the salinity interface, we now have a stratification that is no longer stable in density: while the water now has the same temperature in a thin layer above and below the interface, it is still more salty on top and less salty below the interface. This means that the saltier water in this thin layer is denser than the less salty water below. This leads to finger-shaped instabilities at the interface: The salty water will sink and the fresh water will rise.

The individual salt fingers now have a much larger surface than the original interface, hence molecular diffusion of salt will happen much more efficiently and eventually the salinity inside and outside of the salt fingers will be the same, hence the growth of the fingers will stop.

At the depth where the salt fingers stopped, a new interface has formed. This new interface can also develop salt fingering, leading to a staircase-like structure in temperature and salinity.

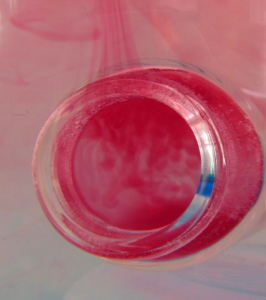

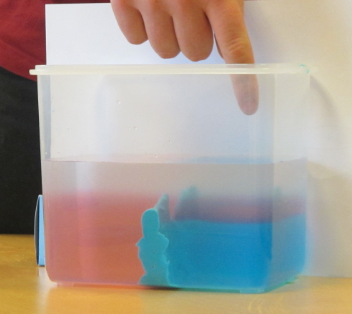

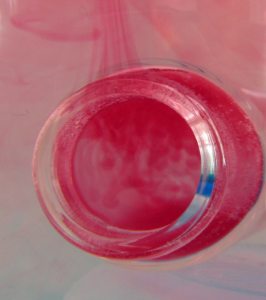

After salt fingering has been introduced, there are usually several other occasions where it, or its effects, can be pointed out, like for example when showing this experiment (see picture below), when talking about the hydrographic properties in the area of the Mediterranean outflow or the Arctic, or when talking about nutrients in subtropical gyres.

This is a zoom in on one of the bottles shown in this experiment: In the warm bottle, the red food dye acts as salt to form salt fingers!

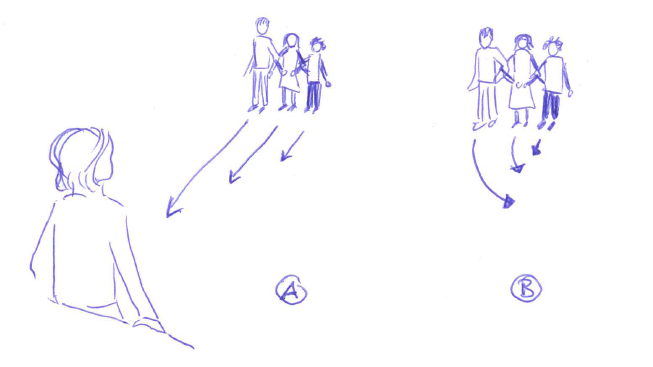

While talking about salt fingering, since I focus so much on the process, I have always been under the illusion that students actually understand the reasoning behind it and that they can reproduce and transfer it. Reproduce they can – transfer not so much. Stay tuned for the next post discussing reasons and possible ways around it.