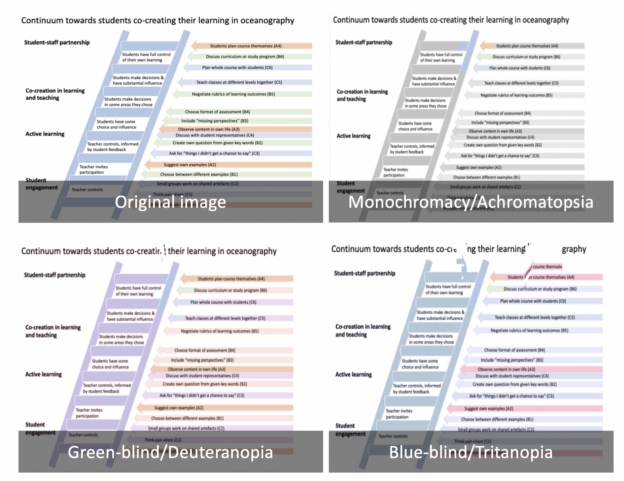

This week, we got super exciting news: Kjersti‘s and my proposal to the active learning call by the Norwegian Directorate for Higher Education and Competence (HK-dir) got funded (perfect timing, since our article on co-creating learning on oceanography was also published this week!)!

Below I’m sharing the translation of an interview that Kjersti gave to the MatNat faculty, but here is a quick overview over what we are planning to do:

Co-creation to promote active learning and communities of practice

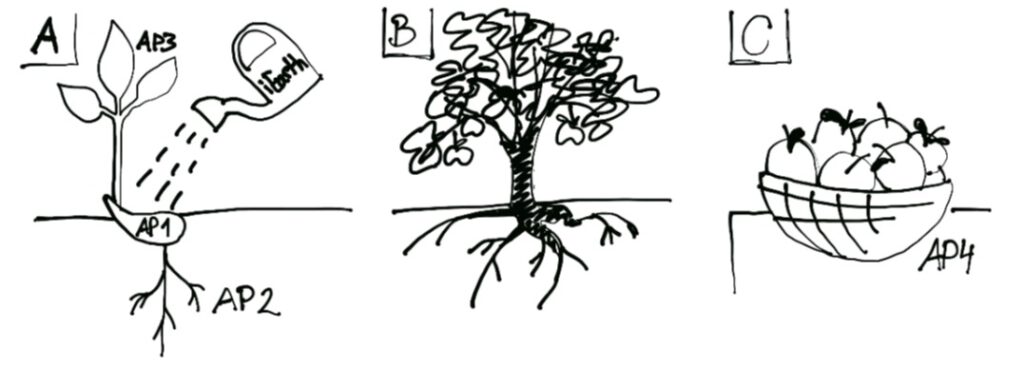

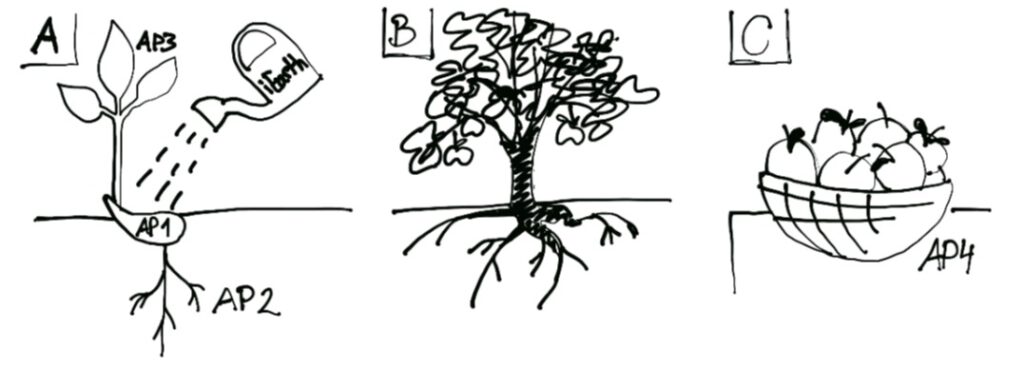

The project’s goal is to use “Co-creation to promote active learning and communities of practice” at the Geophysical Institute at the University of Bergen. We work towards this goal in four work packages (called AP (“arbeidspakke”) in my cheesy illustration below):

In many courses at GFI, the seeds of co-creation are in place and being cultivated already. Our AP1 is about supporting and strengthening those efforts by evaluating and iteratively improving them in some specific courses, in order to gain more experience at our institution and create pilot projects that can serve as proof of concept and that we and others might learn from. In AP2, we help ground those efforts by creating supportive boundary conditions at GFI in terms of looking at how the organisation is structured, whether there are places where student voices could be elevated, and whether the administrative framework could better support co-creation at an institutional level. AP3 is then about engaging more and more teachers and students in other courses in co-creation, and supporting this development by creating meeting places and conversations about the topic, and supporting evaluation and discussion of results. Lastly, we are not doing this alone: AP4 brings together expert advice we are receiving as well as our efforts to share what we are learning. We have the support of the iEarth community, and specifically an advisory board with internationally renowned experts on co-creation and leading academic change processes to help us. As our efforts flower and bear fruit, we will produce a range of publications, infographics, “how-to guides” and many other formats to share our learnings with both the scientific community and interested practitioners.

We are super excited to start working on this with our great colleagues at GFI and within iEarth, and most importantly with our students!

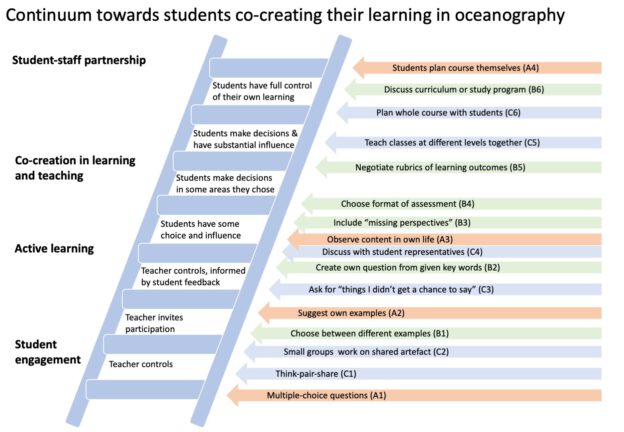

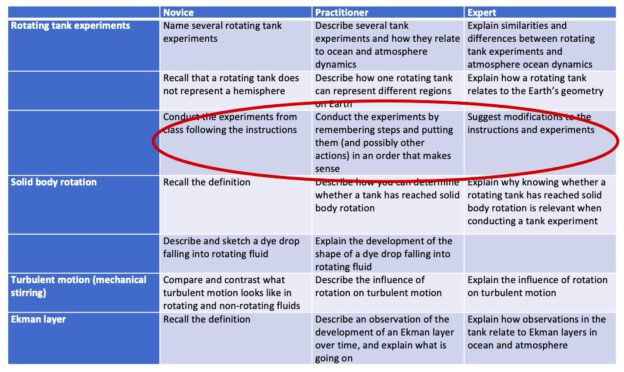

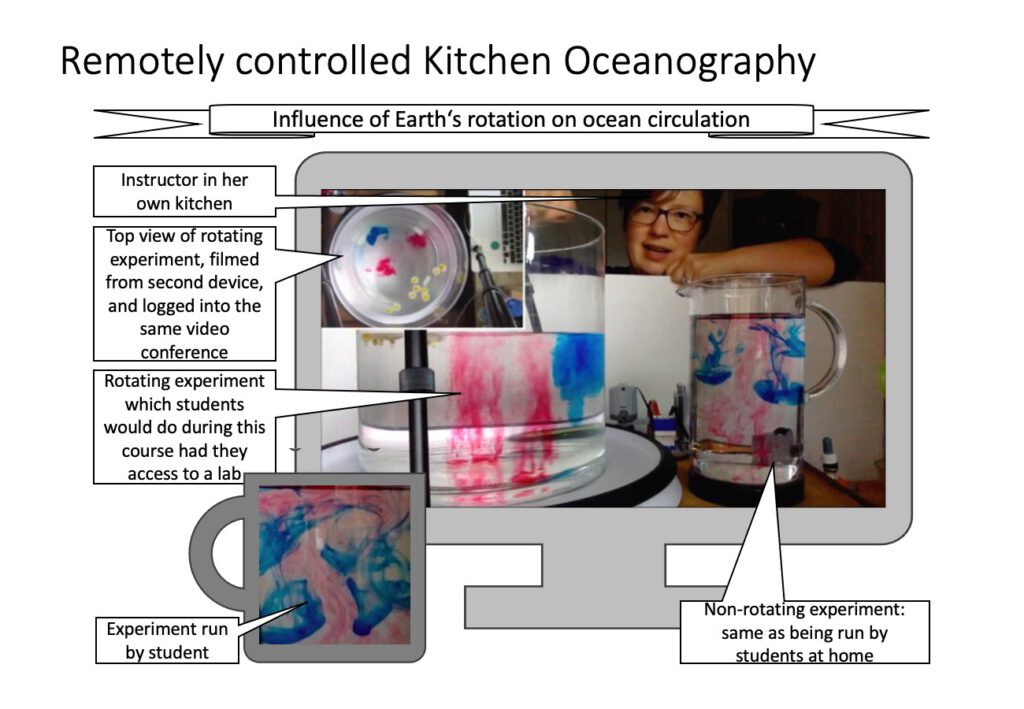

If you are curious about our thoughts on how to get started with co-creating in oceanography (or any other subject, really), Kjersti and I just published an article with some really easy and then some a little more advanced examples (Glessmer & Daae, 2021).

Kjesti’s interview

Kjersti gave an interview to the MatNat faculty who wrote an article about our project. Here is the translation of the questions she was asked and the answers she gave:

How did you come up with the idea for this project?

The Geophysical Institute (GFI) is a partner in the center of excellence iEarth. Together with Mirjam Glessmer (co-author, and Adjunct Associate Professor in iEarth), I have had the opportunity to participate in many discussions with inspiring researchers in both geosciences and education-related research fields. We quickly got in touch with Catherine Bovill and Torgny Roxå (both Adjunct Associate Professors in iEarth) and the Geoscience Education working group at the University of Oslo. All their expertise in the field of co-creation and changing academic cultures fit perfectly with what we want to achieve at GFI. The application therefore was inspired by, and builds on, positive experiences with testing new ways of teaching in introductory courses at GFI with our colleagues there, and dialogue with colleagues and professionals from iEarth.

What is the major weakness of today’s teaching in your subject, and what do you want to improve?

Teaching at all levels, including at universities, is changing. More and more people are moving away from lectures and instead trying out new research-based teaching methods where the focus is on active involvement of students. Through instructional methods that activate the students, the students practice skills such as discussion, analysis, problem solving, sketching, etc. Research shows that students learn more and better from active forms of teaching, even if they do not necessarily experience it that way, or prefer this form of teaching. Teachers therefore appreciate support and guidance in making this transition to more and more active forms of teaching and learning in dialogue with students and leadership.

What does your focus on co-creation and community of practice mean?

Focusing on co-creation and community of practice is largely about changing the relationship between teachers and students, in order to provide students with the best environment for learning during their studies. The students are our most important “customers”. It is important that they are included in everything that happens at the department and university, that they are seen and heard, and that they are given the opportunity to influence their own studies and thus lives.

“Co-creation” encompasses a wide range of student activity and engagement, from individual activities during a single teaching session to larger activities that take place over long time, where students take on responsibility for shaping their learning together with their teachers. In co-creation activities, all participants have the right to contribute equally, but not necessarily in the same way. An increased degree of co-creation can help make teaching more inclusive and increase student engagement; at the same time, students learn more, they experience learning as more relevant, and they develop as democratic citizens. If you are curious about specific examples of co-creation activities, you can take a look at the article Mirjam Glessmer and I recently published in the magazine Oceanography (https://tos.org/oceanography/article/co-creating-learning-in-oceanography).

“Communities of practice” are groups of people who share common interests, where the participants know each other, collaborate on common goals, and develop through the exchange of knowledge. This means that teachers and students encourage and support each other in various forms of development.

So ultimately both co-creation and communities of practice are tools towards more dialogue: between students and teachers as well as within both groups individually.

What kind of responses have you received to the idea in the professional environment and from the authorities?

The very process of writing the application has affected how we think about teaching. We have had many good discussions about teaching and learning with teachers, students, and administration at both GFI and in the new network of colleagues we have found through iEarth. This has been a great help in the development of the idea and the project application, and we have received a lot of support and encouragement to move forward with our plans.

What is the common denominator for the work packages?

The common denominator for the work packages is a change in relations between students, teachers, and administration. Both students and teachers must want change and learn about how change can happen in a good way for all parties. In addition, we must put boundary conditions in place that make the changes possible at the departmental level.

What is culture created to wanting to change teaching?

Everyone involved with a university has their own opinion on how teaching at the university is or should be. This perception often reflects a traditional understanding of the role of teachers and students, where teachers must lecture on subject matter and students must acquire the subject matter and be measured by how well they can reproduce it. As long as these expectations persist, it is difficult to change the relationships between teachers and students. We want to influence teachers and students to change their focus so that teachers learn more with the students, and the students inspire the teachers. This is already happening to some extent, and through this project we want to support and strengthen this change process.

When the project is finished, what is the most important experience you will have gained?

Through a common and consistent focus on co-creation and community of practice, GFI will provide students with the best prerequisites for learning during their studies. We want to be an educational institution that helps students develop on both an academic and a personal level. This is achieved through a better dialogue between students, teachers, and administration and through a continuous development of the teaching culture at the department. When the project is completed, we hope to see a cultural change towards “more students” that is founded in the department and that continues to grow beyond the project. We also want to discuss our experiences with the higher education community and hope to inspire more people to get involved in co-creation and community of practice with the goal of improving education.