Published now: “Activity bingo: Nudging students to make the most out of fieldwork”

Kjersti and I, together with Linda and Francesco, just published an article in Oceanography on the fieldwork bingo we developed for the student cruises earlier this year (and that came quite a long way from our first version as a postcard!). I am currently very much on the bingo-as-a-tool-to-nudge-people-to-do-stuff trip (see also my “Universal Design for Learning” bingo), so I am happy to now have an article I can point people to! So go and read Glessmer, Latuta, Saltalamacchia, and Daae (2023): “Activity bingo: Nudging students to make the most out of fieldwork”!

Below, I share a previous version in which what is now supplementary material is still part of the main body of the text, just because I liked the longer form. But here is the actual article and the full citation:

Glessmer, M.S., L. Latuta, F. Saltalamacchia, and K. Daae. 2023. Activity bingo: Nudging students to make the most out of fieldwork. Oceanography, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2023.217.

Activity bingo: Nudging students to make the most out of fieldwork

by Mirjam S. Glessmer, Linda Latuta, Francesco Saltalamacchia, Kjersti Daae

“[The activity bingo] made the cruise more fun and productive, because it made me pursue tasks and conversations which I would not have engaged in without the bingo, and I learned a good amount of new things.”

– A student in our field course, 2023

In geosciences, fieldwork is a traditional way to teach various applications of disciplinary knowledge and practical skills and to introduce students to the scientific method (Malm, 2021). Many students are excited to join fieldwork and find it motivating and relevant for their future careers. In post-fieldwork surveys, our students typically describe their fieldwork using words like instructive, exciting, fun, interesting, good experience, cooperation, etc. The dominant discourse among geoscience teachers is also that “‘fieldwork is good’ for both social and academic purposes” (Malm, 2021). However, for various reasons, not all students take advantage of all opportunities within the scope of the fieldwork. For many students, there is a wide gap between what they learn through participation in a field course and what they need to be able to do later in more independent fieldwork.

Orion and Hofstein (1994) suggest that the educational effectiveness of fieldwork depends on both the fieldwork quality, i.e., the structure and quality of teaching, and the students’ familiarity with the fieldwork setting, which they refer to as “novelty space.” Fieldwork in geoscience usually takes place outdoors, and in our case on research ships, and often requires a lot of previous experience, skills, and abilities to be comfortable and successful (e.g., know how to dress according to weather, hike in difficult terrain, lift heavy equipment, use manuals to operate scientific instruments, etc.). When students become overwhelmed with such practical issues, it takes focus and energy away from learning disciplinary knowledge and skills (Orion and Hofstein, 1994). Unfortunately, there is also a long history of propagating stereotypes of what a successful geoscientist looks like (“checkered button-down shirts and a beard,” as we have heard colleagues say to first-year students). This culture makes it harder for some students to feel that they belong (Malm, 2021), and we know that experiences of positive relationships are important for student learning (Felten & Lambert, 2020).

We want all our students to be able to make the most out of the valuable learning opportunities that fieldwork presents, and for that purpose, we created gamified activity prompts. Those prompts nudge students, i.e., change their behavior in a desirable way without forcing them or punishing non-compliance (Thaler and Sunstein, 2008), towards seeing, seizing, and even creating opportunities for themselves. In the following, we walk you through our design process of, and our students’ experiences with, our “fieldwork bingo”.

How we create our bingos

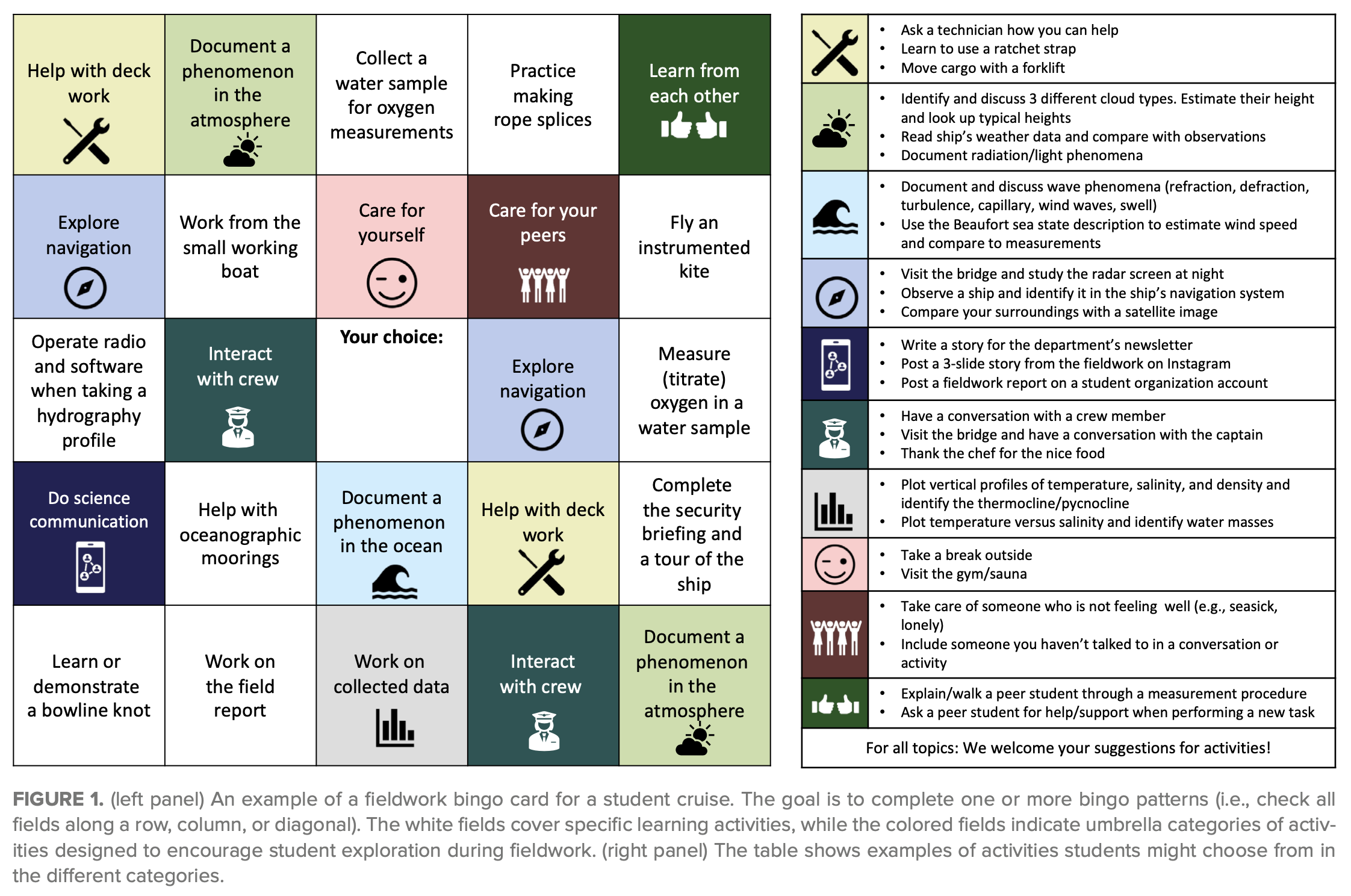

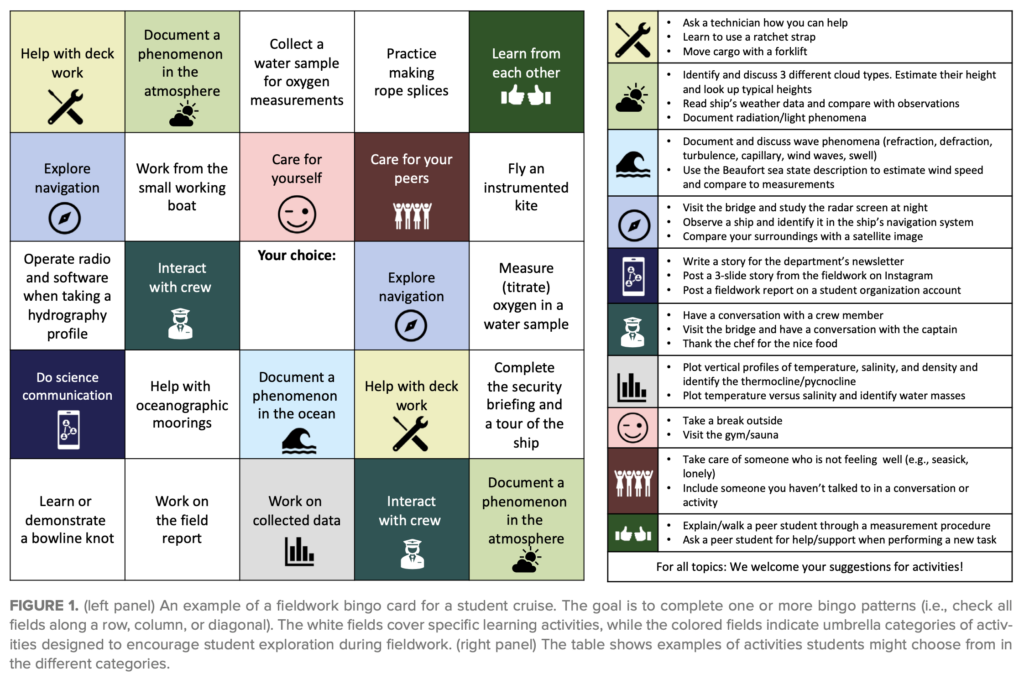

We use a bingo layout to present a wide range of learning activities that we want to encourage students to engage in during the fieldwork. A bingo is more appealing than a checklist, and most students intuitively know how to use it and feel drawn to checking boxes to complete a full row, column, or diagonal. In addition, strategic placement of activity prompts lets us subtly guide students towards certain activities, since some squares are part of more bingos than others. Figure 1 shows an example of a fieldwork bingo for a four-day student cruise on a research ship.

Identifying intended learning outcomes and choosing activities

To create a bingo, we first collect and discuss intended learning outcomes with all teachers and teaching assistants involved in the course. It is relatively easy to identify learning outcomes and relevant activities close to the curriculum that we want to encourage students to engage in during their time onboard. Those activities might not be explicitly mentioned in the curriculum, for example handling specific equipment, taking distinct measurements, documenting the experience for future reports, etc. Activities such as these are typically the reason why we go into the field in the first place, and many students will engage in them, but some need the extra prompt. This is especially relevant on cruises with large numbers of students, where only a few students at a time can perform a specific task. Ensuring that everyone participates in a variety of activities can become challenging because of the difficulty of tracking individual contributions. A fieldwork bingo increases the probability that every student engages in a basic set of tasks, facilitating a comprehensive experience for all.

Identifying the better-hidden part of the curriculum often takes more effort. Good indicators of what might be useful to include in a bingo are recollections of situations where we noticed some students (or sometimes even us instructors) eagerly creating interesting and beneficial learning opportunities for them- (or our-)selves, that other students did not show any interest in. Other ideas can come from conversations with other people involved in the fieldwork, for example, the crew on a research ship. We reflect on what useful learning students may miss out on if we do not encourage them explicitly (for example, related to the “etiquette” on a research ship; Glessmer, 2019), and create corresponding activity prompts.

Placing activities on the bingo board

We then categorize and prioritize activities. Some activities we deem so important that we want to include them explicitly in their own fields, for example, ‘collect a water sample for oxygen measurements’. We also offer the opportunity for each student to choose activities that have personal relevance for them by including umbrella categories. There, students choose from a list or suggest their own activities that are relevant in that category. For those umbrella categories, it is more important to us that students think about the category in general, than what exactly the students do. Such categories include practical work, social interactions with peers and crew members, and connecting theoretical disciplinary knowledge to observations of the real world. We leave the center square empty to allow students to freely suggest their own activities. All these “choice” fields encourage students to actively think about what other activities or experiences they might benefit from and want to seek out, to better connect different tasks with disciplinary content, expand their horizons, and take ownership of their learning. Finally, we also include some low-threshold activities in the bingo (for example, participation in the security briefing, which is mandatory for all students anyway), to get students started.

Adapting a bingo

We adapt bingos specifically for each instance we use them, not just in terms of the intended learning outcomes of a course, but also depending on the context the course is given in. For example, if students do not know each other well before the fieldwork, they benefit especially from activities that provide them with opportunities to socialize and get to know each other.

When the students are introduced to the bingo, cultural aspects need to be considered, too; for example, whether competition will be perceived as motivating or not (e.g., if the perception is that the “winners” are pre-determined due to very different prior knowledge or similar). Giving rewards for students who complete a bingo (first, or at all) can be perceived as extra motivation. But rewards should be used with caution, as they can also undermine intrinsic motivation (Kohn, 1993).

The technical realization of our bingo is very simple. We created a table in PowerPoint and coded both the table and list of suggested activities for accessibility with a color-blind friendly palette as well as with icons. An editable PowerPoint document of the bingo shown in Figure 1 can be downloaded at https://cocreatinggfi.w.uib.no.

Student perceptions of our bingo

We ran fieldwork bingos on two student cruises on board research ships with four continuous days at sea each. The cruises were embedded in physical oceanography and meteorology study programs. During their time at sea, all students completed at least one bingo. Despite the limited time and the bingo being introduced as completely voluntary, some students got up to 8 bingos. But what aspects of the bingo made the experience motivating and valuable for students?

In response to open questions about their experience with the bingo, one student states: “[The bingo] positively influenced the [fieldwork] experience, since [the bingo] challenged us to do various things we would not necessarily try out“. Several students commented similarly that the bingo gave them “motivation to explore and build on existing skills,” “increased motivation to try out non-disciplinary activities,” or “helped me to be even more curious and active than I usually am, since it added a “game” feature and a bit of healthy competitivity to the different objectives.”

In the following, we structure student feedback according to the three components of self-determination theory that support intrinsic motivation: relatedness, competence, and autonomy (Deci & Ryan, 2000), which are clearly identifiable in the student responses we received.

I feel connected!

We created opportunities to experience positive relationships and relatedness with peers, teachers, and the crew. Students noticed this and expressed that the bingo “encouraged students to interact with each other” and served as a “teamwork opportunity: For instance, some students shared good tips on identifying cloud types, whereas others knew how to find vessels from the global vessel positioning data. By helping each other, we got to spend more time together outside of the class activities, and it has helped our teamworking skills and encouraged communication“. Especially on the student cruise where the students did not know each other well, students appreciated the “ice breaker,” that made “socializing with peers, whom I didn’t know so well from before, easier.” Even though not explicitly mentioned by the students, the bingo is also an opportunity for students and teachers to have informal conversations about disciplinary content and beyond, thus building relationships and lowering the threshold for future interactions.

The students also understood that the staff and the crew members welcome interaction. An experienced student writes: “the thing that I enjoyed the most, and that surprised me because I never noticed it on all my previous cruises, was to see how open to a chat or to answer questions the crew is. They always seem very serious and preoccupied with all their different tasks, and I never really thought of interacting with them for anything more than what was needed for our sampling purposes. I enjoyed spending some time practicing knots with [another student] and a crew member on deck, and that served not only to tick off another task, but also to break the ice and provide conversations with the same crew member and others during the following days. The bingo also motivated me to go up to the bridge to follow some sampling operations or study the radar, and I had interesting conversations with the captain and other crew members. It is sometimes hard for scientists to remember that we can learn a lot from people with different types of experiences, and in my next cruises I will definitely keep this in mind.”

I feel capable!

We also included tasks that the learner can do with guidance or figure out together with their peers (Vygotsky, 1978), especially regarding developing practical skills that help students solve challenges in fieldwork. One student writes: “I liked how the game was designed, with different activities ranging from the easy and fun (say ‘thank you for the food’ to the chef) to the more scientific ones. Having some low-bar activities helped to get some tasks ticked off already as we got the bingo sheet, which made all of us more eager to do the rest.”

The bingo helped students feel engaged with the fieldwork because it “gave us something to do during quiet periods of the shift,” for example, during night watches, by encouraging them to “spend the time on something we learn from and that is useful.” It also encouraged them to connect relevant disciplinary knowledge with their experience, which gave them a feeling of mastery: “When walking on the outer decks to take photos of the fjords I enjoyed noticing that a part of my mind was focused on detecting the different phenomena which could be observable in the water or in the atmosphere“, as one of the bingo activities suggested.

The feeling of competence was not limited to the time students were at sea but also manifested in the usefulness of the real-life skills later: The “cruise bingo has facilitated learning new skills which became helpful outside of that particular cruise/course. For example, one of the cruise bingo activities was to learn how to tie a knot. It was not my first cruise, yet I have never asked the crew to teach me this fundamental skill. This time, the cruise bingo motivated such interaction, and I learned one of the knots from an engineer on board. Shortly after the cruise, I was on fieldwork, where we needed to secure some equipment with a rope, and it came in handy to have learned this skill through the cruise bingo.”

I have choice!

Lastly, we wanted students to choose what to do, when, and whom to do it with to co-create their learning (Glessmer & Daae, 2022). One student stated: “it was fun to be creative and make up my own suggestions for the bingo,” and another student stressed: “to start with, everything is more fun when there is a game and competition. The bingo made us constantly look out for work tasks that were not directly linked to our [individual] projects.” The bingo also changed how students perceived their surroundings: “I was constantly on the lookout for atmospheric/oceanographic phenomena.”

Providing choice is also important for accessibility (Behling & Tobin, 2018). A student elaborates: “having room for choice in some of the bingo squares was a good idea. It allowed each student to participate in the bingo activities within their comfort limits while trying new experiences and engaging with a new environment. Such freedom motivates students to explore and build upon their existing skills and does not enforce activities they might not want to engage in, which are not academically compulsory. For example, someone who might have social anxiety about interacting with the crew members could still participate in the bingo without being excluded or pushed beyond their comfort.”

The students took the “free choice” option seriously and chose tasks that were meaningful to them and deserved highlighting, both to themselves and the teacher. Those “free choice” tasks roughly fell into three categories: Taking responsibility for “household chores” (e.g., “tidying up the mess in the water samples”); learning useful skills (e.g., soldering); or science communication (e.g., documenting the work for the institute’s newsletter).

What the students did not say

We gave neck warmers to all students when they completed their first bingo. The neck warmers were inexpensive giveaways, but of practical use on a cruise (to wear under a helmet), and we did observe students trying to finish off their first bingo in order to get one. However, none of the students mentioned them as the reason they were motivated to engage with the bingo without explicitly asking students about it. So even though the small rewards seemed to be appreciated, they did not seem to have a big influence on the students’ perception of the bingo.

Improving future bingos

Complementing what students reported after the cruise, we observed a lot of positive interactions between students and staff, students attempting and succeeding at new-to-them tasks, and using their time on the ship to explore many different aspects of this unique opportunity. We conclude that the bingos served their purpose, and we are thinking about how to use and improve them going forward.

Before, during, and after this experience, we have had many interesting discussions with other teachers and students who see the potential of using similar bingos in their context. For example, one of the experienced students participating in our cruise will be teaching a field course later this year and writes: “the bingo helped me in understanding a bit better what motivates students to get engaged in more activities, and how to make learning feel more “voluntary” and entertaining. I am currently thinking of making a different version for the students of our […] cruise in September.”

Now that you have seen what we do and how we and our students think about it, we are curious to hear your thoughts! How will you use bingos in your context? What suggestions do you have for improving our bingo? Please reach out!

References

Behling, K. T., & Tobin, T. J. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: Human needs and the self- determination of behavior. Psychological inquiry, 11(4), 227-268.

Felten, P., & Lambert, L. M. (2020). Relationship-rich education: How human connections drive success in college. JHU Press.

Glessmer, M. S. (2019). What’s the etiquette on a research ship? “Soft skill” learning outcomes on a student cruise. Blogpost available at https://mirjamglessmer.com/2019/02/07/whats-the-etiquette-on-a-research-ship-soft-skill-learning-outcomes-on-a-student-cruise/

Glessmer, M. S., & Daae, K. (2022). Co-Creating Learning in Oceanography. Oceanography, 35(1), 81-83.

Kohn, A. (1994). Punished by Rewards: A Rejoinder. Beyond Behavior, 5(2), 4-6.

Thaler, R. H., & Sunstein, C. R. (2007). Nudge: Improving decisions about health, wealth, and happiness: Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2008, 293 pp.

Malm, R. H. (2021). What is fieldwork for? Exploring Roles of Fieldwork in Higher Education Earth Science. PhD thesis at the University of Oslo, Norway, available at https://www.duo.uio.no/handle/10852/82828

Orion, N., & Hofstein, A. (1994). Factors that influence learning during a scientific field trip in a natural environment. Journal of research in science teaching, 31(10), 1097-1119.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society. The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Edited by Cole, M., John-Steiner, V., Scribner, S., & Souberman, E. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Exploring the UDL 3.0 version, inspired by an episode on the Tea for Teaching podcast - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] and relatedness; joy and play with activities like active lunch breaks, kitchen oceanography, bingos; and then of course sensitivity to identities and […]

Structuring fieldwork as a jigsaw to increase student responsibility in, and ownership of, their projects - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] outside of the environment where they will be applied. We have previously shared some ideas for how to nudge students to make the most out of fieldwork (using a cool bingo!), but here is another idea that Kjersti and Hans-Christian implemented and that really improved […]