Structuring fieldwork as a jigsaw to increase student responsibility in, and ownership of, their projects

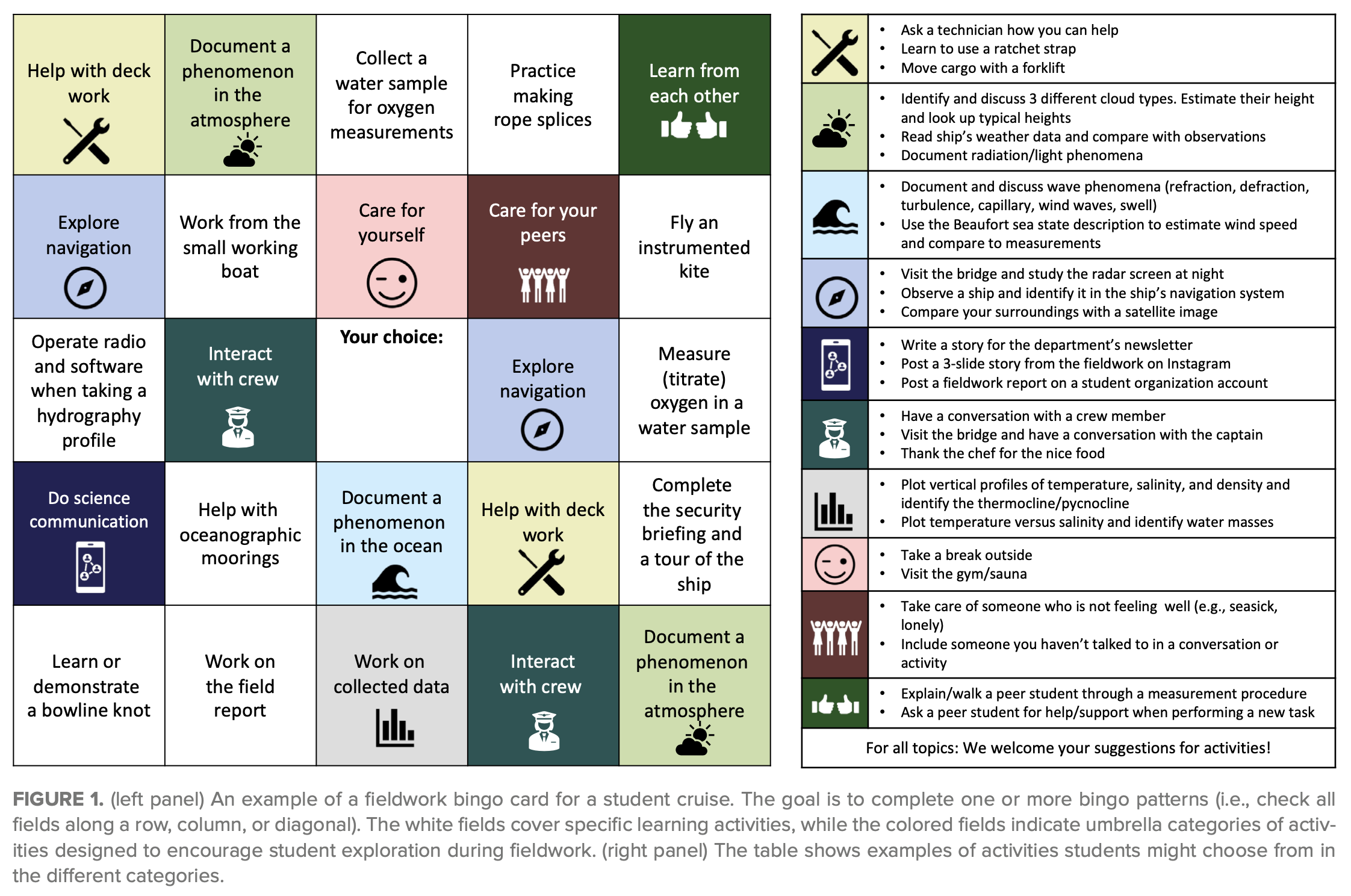

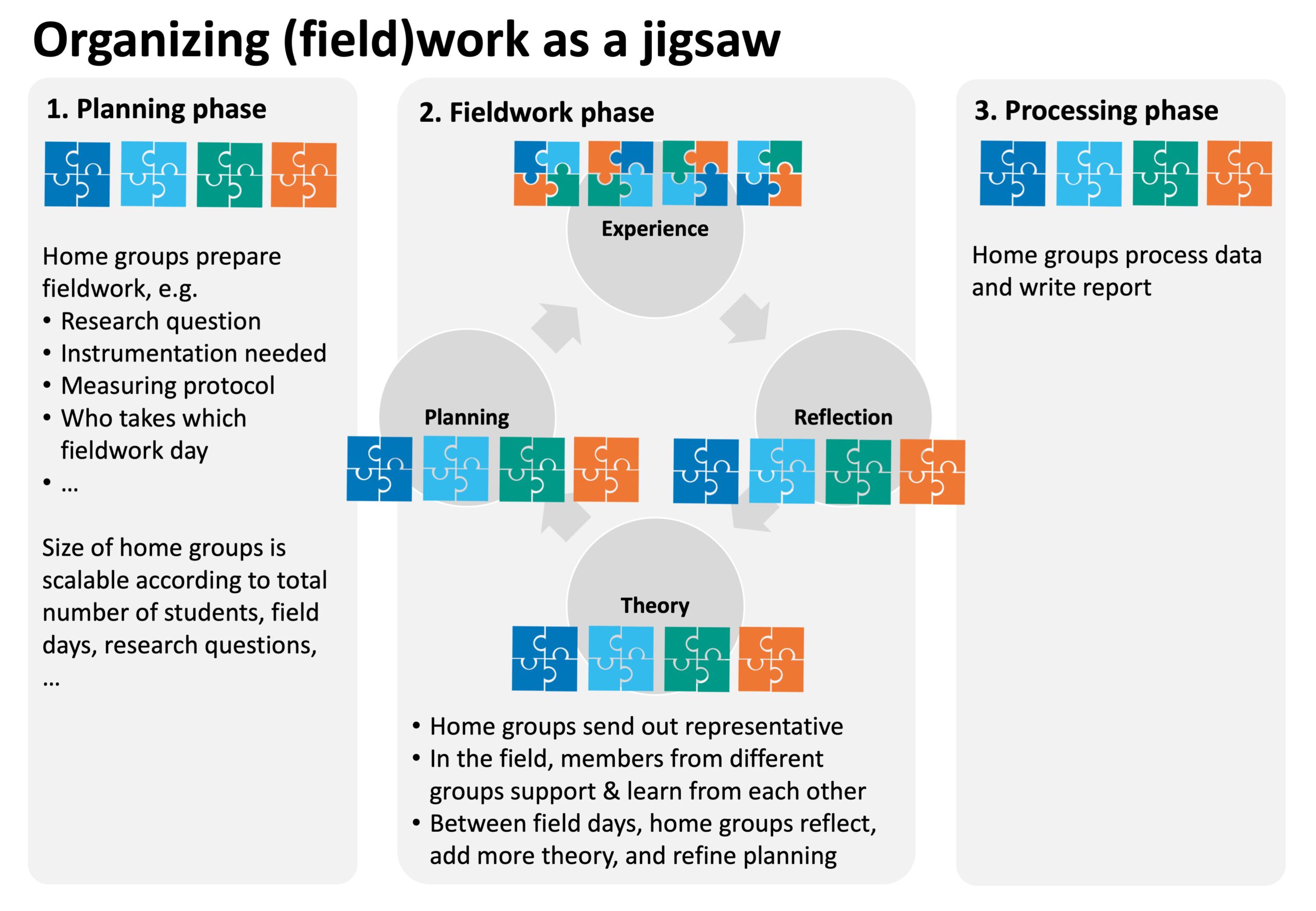

I am a huge fan of Kjersti‘s excellent teaching, it is always so inspiring! She, together with Hans-Christian, developed a jigsaw method to structure preparation for a student cruise, the cruise itself, and then writing of cruise reports. We wrote it up and submitted it for a forthcoming book on field teaching (which I will […]