A little bit of hands-on meteorology for a change.

This post is inspired by www.planet-science.com‘s “fog in a bottle” and “make a cloud in a bottle” posts. Inspired meaning that I had to try and recreate their experiments after I saw this when approaching Zurich airport recently:

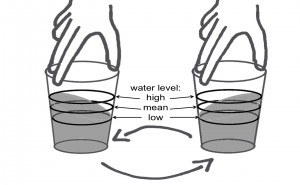

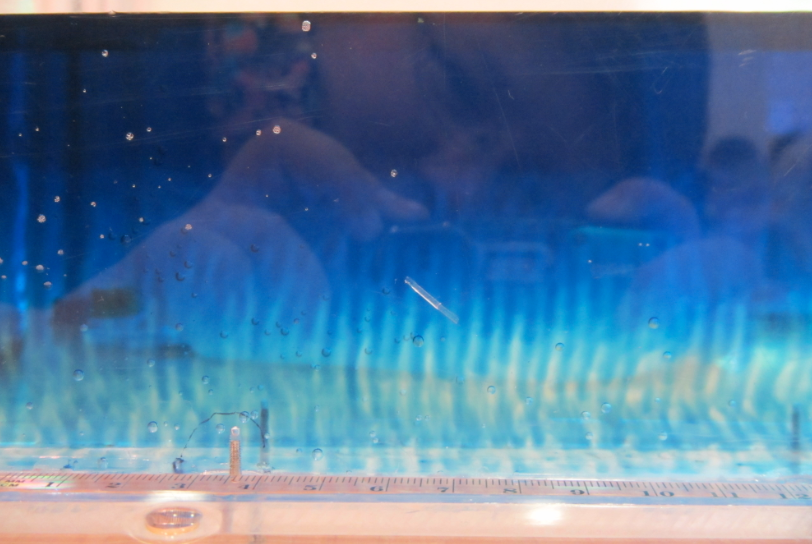

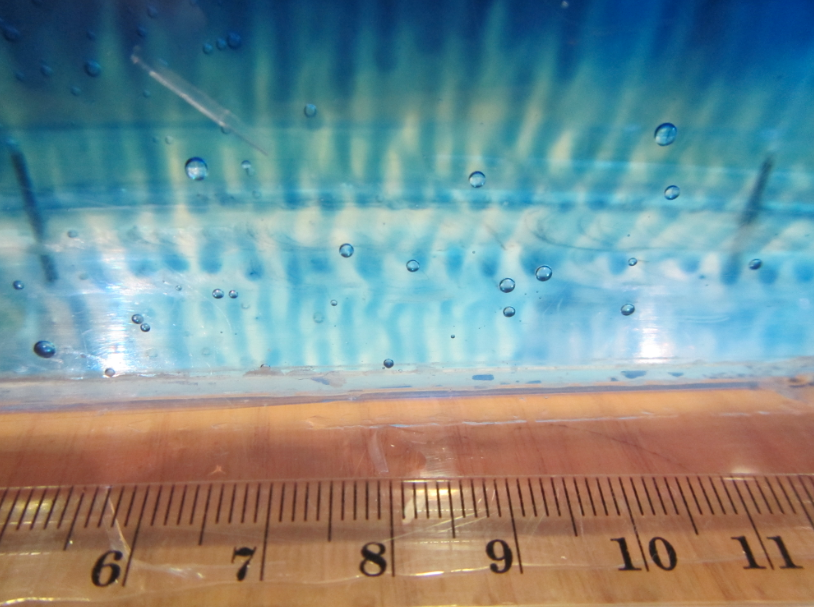

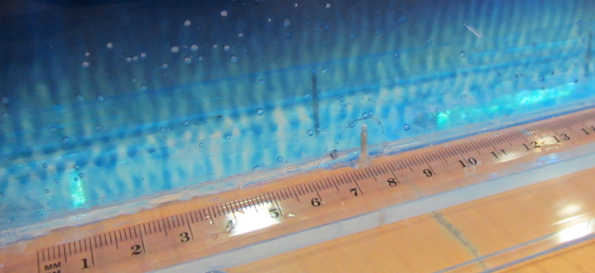

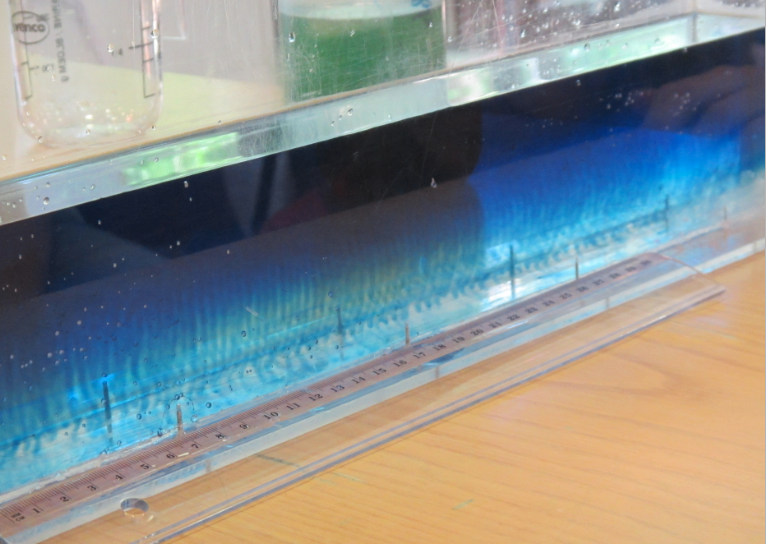

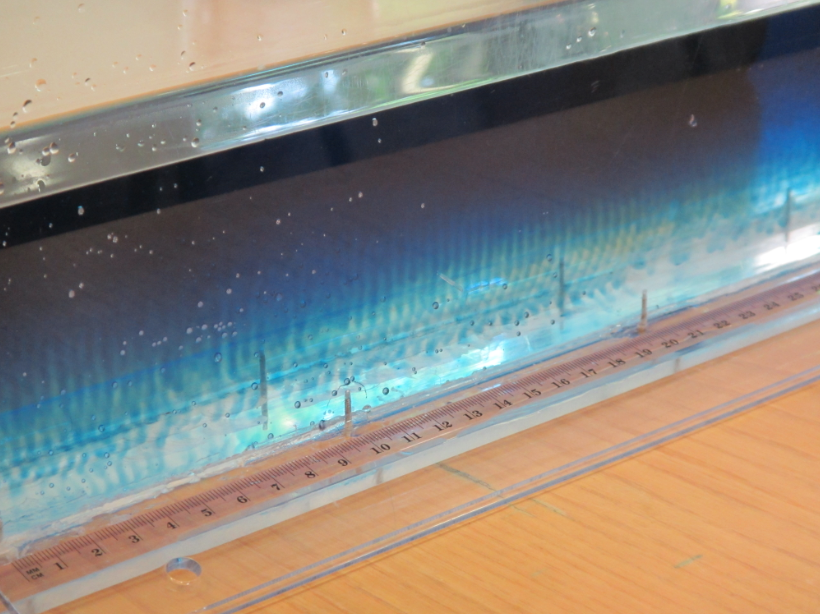

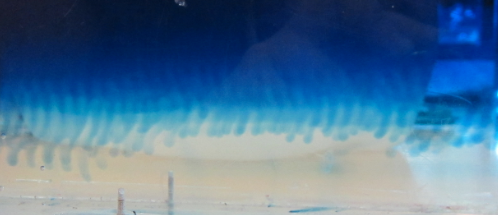

So let’s start with fog in a bottle. I’m doing fog in a jar, because it is easier to balance a sieve with ice cubes on a wide-mouthed jar than on a bottle… There is about 2 cm of hot water in the jar and the sieve with ice cubes is put on top to cool the moist air enough for fog to form.

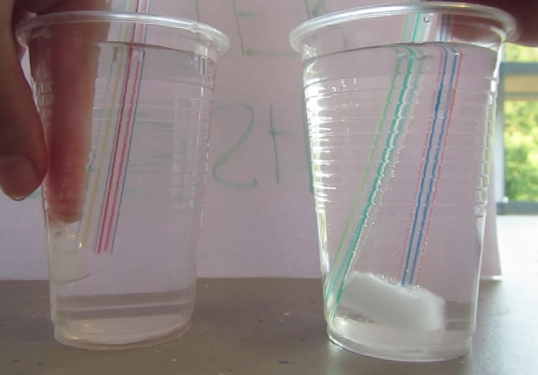

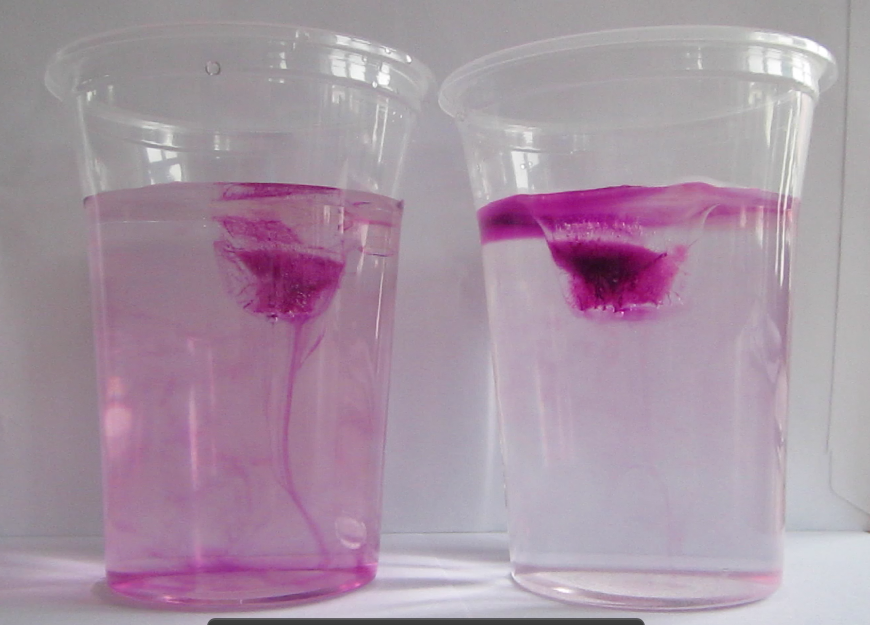

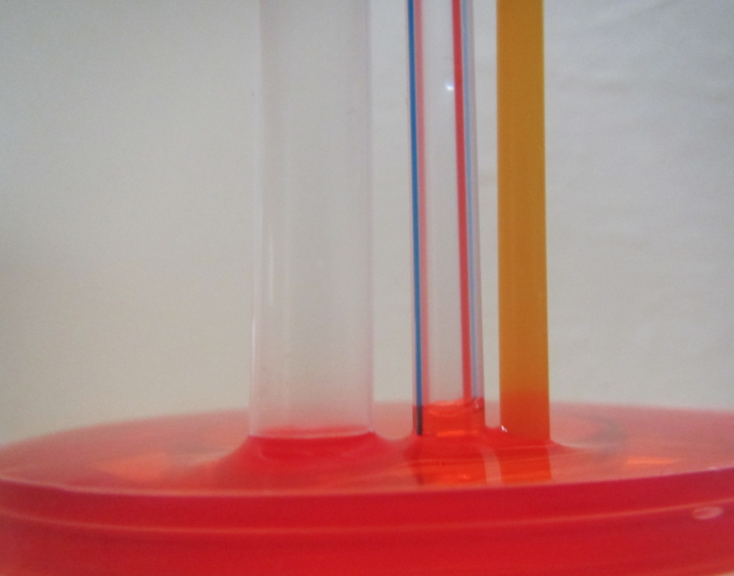

And now the cloud in a bottle. This one is fun! And a lot more impressive in the flesh than in the movie, so try it out yourself! Suck some smoke into a bottle that contains a little water. Close the cap, press and release the bottle and see a cloud forming when you release it. The smoke acts as condensation nuclei here. And pressure changes, temperature changes, yada yada… Anyway, try it yourself!

P.S.: Kristin – erkennst Du die Flasche? Die, die Deine Freundin Dir mitgegeben hatte, damit Du was zu trinken hast, die dann mit in Göteborg war und die ich dem Recycling zuführen sollte? Hat offensichtlich nicht geklappt, aber viele Grüße an Deine Freundin! :-)