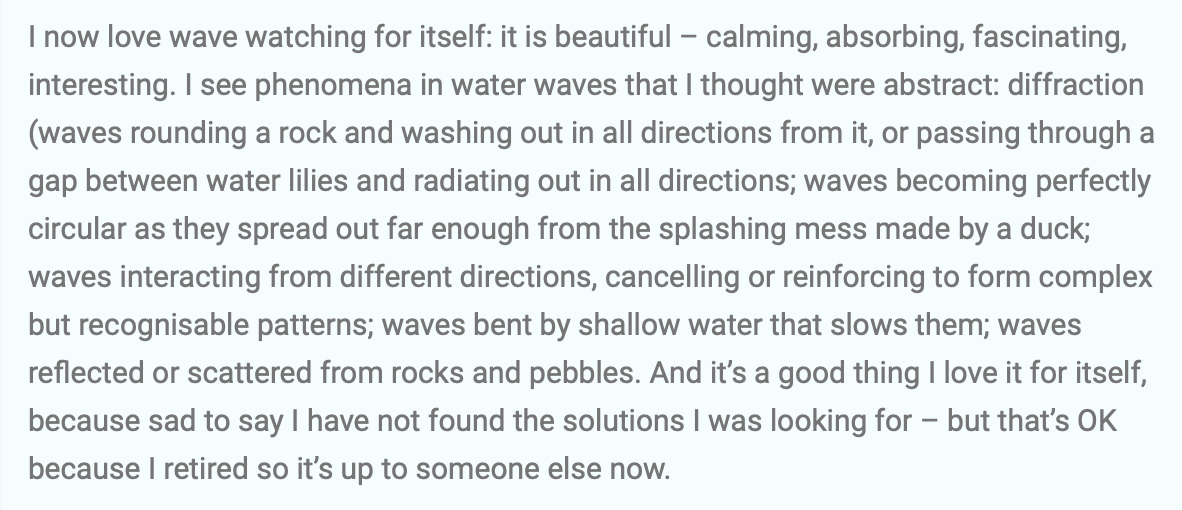

Guest post by Kirsty Dunnett: “Disembodied Science: On why the abstract is difficult to grasp, and some thoughts on the imperceptibility of impending(?) climate disaster”

My most faithful guest blogger Kirsty writes about why things that are far outside of our direct experience are so hard to imagine and thus so hard to understand (and teach).