A tool to understand students’ previous experience and adapt your practical courses accordingly — by Kirsty Dunnett

Last week, I wrote about increasing inquiry in lab-based courses and mentioned that it was Kirsty who had inspired me to think about this in a new-to-me way. For several years, Kirsty has been working on developing practical work, and a central part of that has been finding out the types and amount of experiences incoming students have with lab work. Knowing this is obviously crucial to adapt labs to what students do and don’t know and avoid frustrations on all sides. And she has developed a nifty tool that helps to ask the right questions and then interpret the answers. Excitingly enough, since this is something that will be so useful to so many people and, in light of the disruption to pre-univeristy education caused by Covid-19, the slow route of classical publication is not going to help the students who need help most, she has agreed to share it (for the first time ever!) on my blog!

Welcome, Kirsty! :)

A tool to understand students’ previous experience and adapt your practical courses accordingly

Kirsty Dunnett (2021)

Since March 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic has caused enormous disruption across the globe, including to education at all levels. University education in most places moved online, while the disruption to school students has been more variable, and school students may have missed entire weeks of educational provision without the opportunity to catch up.

From the point of view of practical work in the first year of university science programmes, this may mean that students starting in 2021 have a very different type of prior experience to students in previous years. Regardless of whether students will be in campus labs or performing activities at home, the change in their pre-university experience could lead to unforeseen problems if the tasks set are poorly aligned to what they are prepared for.

Over the past 6 years, I have been running a survey of new physics students at UCL, asking about their prior experience. It consists of 5 questions about the types of practical activities students did as part of their pre-universities studies. By knowing students better, it is possible to introduce appropriate – and appropriately advanced – practical work that is aligned to students when they arrive at university (Dunnett et al., 2020).

The question posed is: “What is your experience of laboratory work related to Physics?”, and the five types of experience are:

1) Designed, built and conducted own experiments

2) Conducted set practical activities with own method

3) Completed set practical activities with a set method

4) Took data while teacher demonstrated practical work

5) Analysed data provided

For each statement, students select one of three options: ‘Lots’, ‘Some’, ‘None’, which, for analysis, can be assigned numerical values of 2, 1, 0, respectively.

The data on its own can be sufficient for aligning practical provision to students (Dunnett et al., 2020).

More insight can be obtained when the five types of experience are grouped in two separate ways.

1) Whether the students would have been interacting with and manipulating the equipment directly. The first three statements are ‘Active practical work’, while the last two are ‘Passive work’ on the part of the student.

2) Whether the students have had decision making control over their work. The first two statements are where students have ‘Control’, while the last three statements are where students are given ‘Instructions’.

Using the values assigned to the levels of experience, four averages are calculated for each student: ‘Active practical work’, ‘Passive work’; ‘Control’, ‘Instructions’. The number of students with each pair of averages is counted. This leads to the splitting of the data set, into one that considers ‘Practical experience’ (the first two averages) and one that considers ‘Decision making experience’ (the second pair of averages). (Two students with the same ‘Practical experience’ averages can have different ‘Decision making experience’ averages; it is convenient to record the number of times each pair of averages occurs in two separate files.)

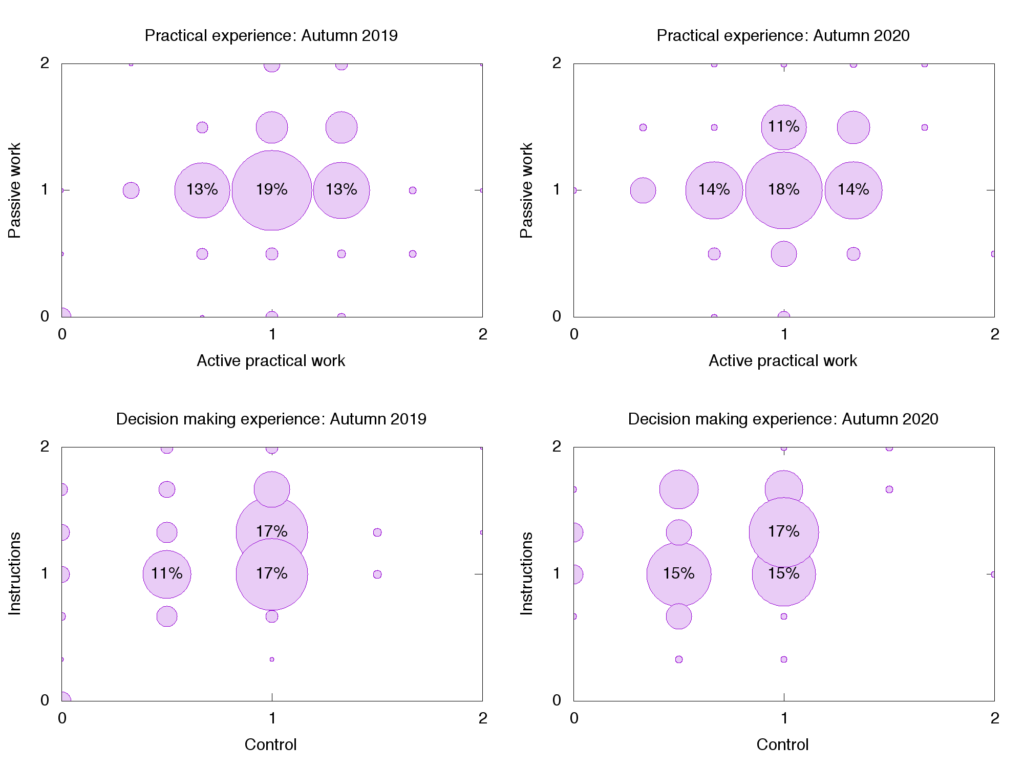

To understand the distribution of the experience types, one can use each average as a co-ordinate – so each pair gives a point on a set of 2D axes – with the radius of the circle determined by the fraction of students in the group who had that pair of averages. Examples are given in the figure.

Prior experience of Physics practical work for students at UCL who had followed an A-level scheme of studies before coming to university. Circle radius corresponds to the fraction of responses with that pair of averages; most common pairs (largest circles, over 10% of students) are labelled with the percentages of students. The two years considered here are students who started in 2019 and in 2020. The Covid-19 pandemic did not cause disruption until March 2020, and students’ prior experience appears largely unaffected.

With over a year of significant disruption to education and limited catch up opportunities, the effects of the pandemic on students starting in 2021 may be significant. This is a quick tool that can be used to identify where students are, and, by rephrasing the statements of the survey to consider what students are being asked to to in their introductory undergraduate practical work – and adding additional statements if necessary, provide an immediate check of how students’ prior experience lines up with what they will be asked to do in their university studies.

With a small amount of adjustment to the question and statements as relevant, it should be easy to adapt the survey to different disciplines.

At best, it may be possible to actively adjust the activities to students’ needs. At worst, instructors will be aware of where students’ prior experience may mean they are ill-prepared for a particular type of activity, and be able to provide additional support in session. In either case, the student experience and their learning opportunities at university can be improved through acknowledging and investigating the effects of the disruption caused to education by the Covid-19 pandemic.

K. Dunnett, M.K. Kristiansson, G. Eklund, H. Öström, A. Rydh, F. Hellberg (2020). “Transforming physics laboratory work from ‘cookbook’ to genuine inquiry”. https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.12831

Apostolos Deräkis says:

Very interesting article! Supposing* that we can trust the data students give us, what does that tell us about setting a realistic, personilased target for the end of the term (as opposed to some guidance on how to run the next educational activity)

*even if students accurately report what has happened, is that closely related to their aptitude and skills? Or maybe just a reflection of the opportunities they happened to have?

Apostolos Deräkis says:

(replying to my own comment here… :-) )

I am still reflecting on this… what is the important factor here? the students’ past experience?

How should we go about identifying their *aptitude* towards enquiry learning, both at the personal and group level?

Kirsty Dunnett says:

Hi!

So it’s certainly not designed for individual tailoring or evaluation, but for higher level instructional design. In a large part it will simply reflect the opportunities students have had, which is why it’s so important to collect one’s own data, and do so every year if possible.

Should there be any reason to *not* trust students when reporting on their past experience? They’re certainly going to have a better idea of what they did than any staff who passed the equivalent level many years ago and possibly in an entirely different educational system.

It should provide an indication of what sort of thing it may be reasonable to ask of students. For example, that most students have had *some* experience of control over practical work indicates that providing a modifiable experimental set up and a basic task, perhaps with theory, and asking students to create their method would probably be appropriate in terms of providing sufficient structure while also encouraging independence – planning, thinking, decision making etc.

A lot of ‘aptitude’ can probably be developed through experiences that support development, but alignment of courses often focusses on assessment rather than checking that provision is appropriate.

One reason for never considering individual tailoring is that it may widen inequities by grouping those who have more confidence or have had more previous opportunities together and even encouraging them to gain experiences that others are not able to share in.

I hope that makes sense. In short: trust your students and they requite your trust; consider development without asking students to do something that is likely to harm their self-efficacy or deliberately benefitting those who have already got/had plenty of advantage (don’t harm them, but, more importantly, don’t leave anyone behind).