Haha, I ended my post this morning with “…but at that point I lost interest”, and apparently that’s a great call to action! Kirsty Dunnett, faithful guest blogger on my blog, volunteered to send me the summary of what I had missed! Thanks for sharing, Kirsty, the floor is yours:

Every so often, Mirjam writes about something she’s reading and it aligns almost exactly with what I’ve been thinking. This is one of those cases – but my interest is in the second part of the article: the relation between academics’ understandings of process and outcomes.

In particular, I’ve recently been thinking about how practical work in physics (and possibly other sciences) often seems to be placed as the teaching process (perhaps at more introductory levels), engagement or participatory opportunities in which, as well as the specific activities, students will develop generic attributes. Moreover, these may be almost the only contexts in which opportunities to develop these skills are present, or at least without potential penalisation. Thus, in addition to practical skills that can only be learned in the applied context, one might not be surprised to find that these courses (or parallel project courses) are also almost the only places in a degree scheme where generic attributes such as group work, planning and various writing and presentations skills are explicit learning outcomes. (Things might have changed in the last decade or so since I was more or less directly in contact with courses, but I would not be surprised if this is still more the rule than the exception.)

When it comes to thinking about what students are asked to do in relation to practical work, one cannot help but think that there’s quite an imbalance…

So, back to (or onwards with) Barrie’s article.

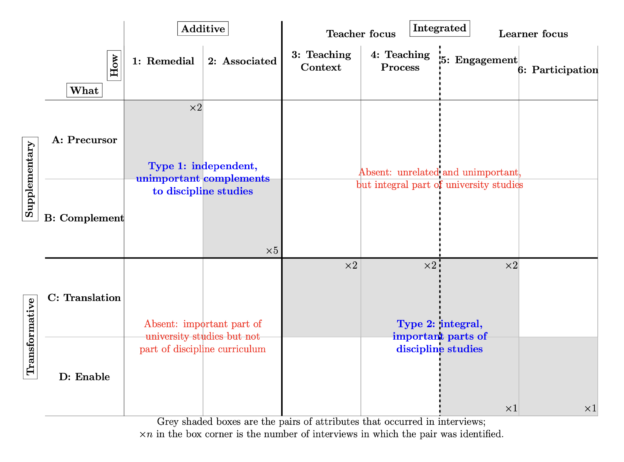

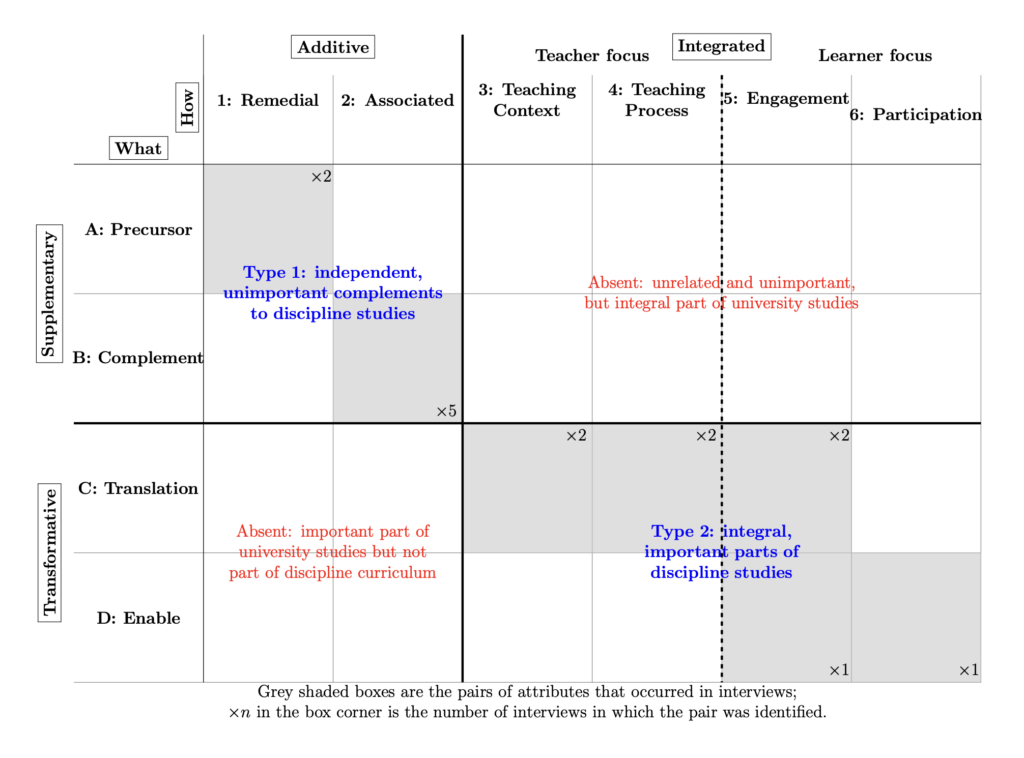

Having described the conceptual framework (as Mirjam’s summarised), the paper then continues to consider what the interviewed academics say about the relation between how generic attributes are taught (or incorporated) into students’ university studies, and what assumptions staff are making about the nature of generic attributes: whether they are precursors to university studies, complement them, are necessary to translate between the disciplinary content of their studies and application beyond the learning context, or are enabling abilities that are integral to university studies. Unfortunately, at least in the copy of the article I have downloaded, the relevant figure is blurry and basically impossible to read (but I did manage to decipher enough to create an abbreviated version, see below).

From the interviews, Barrie found that this 6 x 4 grid can be split into 4 segments. From which three distinct approaches to teaching generic graduate attributes can be identified.

In the first segment (Type one in the figure above), “Generic attributes are unrelated and relatively unimportant outcomes that graduates might posses in addition to the usual learning outcomes of a university education; as such they do not form part of the usual university curriculum. If they are taught at university, it is in a separate supplementary curriculum.” (That is: additive, complementary, unimportant.) This perspective was held by seven of the 15 staff they interviewed (developing generic attributes as complementary skills to discipline knowledge and accorded separate, dedicated courses was the most common structure).

The other segment (Type 2 in the figure above) that was present in the interviews (which Barrie breaks into two sub-sections according to whether the interviewee gave a teacher- or learner-focussed description) is that “Generic attributes are important outcomes that interact with and transform the other learning outcomes of a university education; as such they are an integral part of the usual university curriculum.” (Important, integral.)

Two segments are logically self-contradictory and (perhaps reassuringly) did not turn up in any of the interviews. These are the beliefs that:

a) “Generic attributes are unrelated unimportant outcomes that graduates might possess in addition to the usual learning outcomes of a university education; as such they are an integral part of the usual university curriculum.” (Additive, integral.)

b) “Generic attributes are important outcomes that interact with and transform the other learning outcomes of a university education; as such they do not form part of the usual university curriculum I teach.” (Supplementary, transformative.)

Despite the correlation of the two different (related) scales that Mirjam’s post described, the interviewed academics did not explicitly describe the relationship between the teaching approaches and the nature of these graduate attributes; however, within the exploratory, phenomenographic nature of the study, the causal relation is not in focus… As they remark, this work could be the first stage in a larger, quantitative study (has this been done? I haven’t looked), as well as pointing towards some inherent tensions in modern university teaching and the, often institution- or government-driven explicit inclusion of generic graduate attributes to degree programmes.

Which brings me back to labs: from this data, my observations and experience that a large number of physics courses merrily ignore generic attributes and focus almost exclusive on theoretical knowledge (beyond, perhaps, problem solving, the development of which is facilitated by worksheets that can be marked against pre-determined correct answers), while students are expected to develop transferable skills (or generic attributes) in already time-limited and even de-emphasised practical and project-courses is not something that happens… Could this be because the interviewees in the study had a ‘labs in course’ structure, so the generic attributes were in the course, and any localisation to specific parts of the course was not identified, while I come from a system that typically has separate courses for practical work? Or is it because practical work (of all sorts) is actually seen as part of the ‘secondary curriculum’ and therefore not ‘proper physics’?