“Methoden to go” by E.-M. Schumacher, which you see in the picture above, is a handy collection of well- and less-well-known methods for university teaching, organised by the six different phases of a typical session (getting into a topic, learning about a topic, discussing it, applying knowledge, securing results, and ending a lesson). It’s a collection of colourful flashcards that are loosely bound together, with a short description of a method on either side. I love the format — it’s playful and great to browse for inspiration; flipping through the cards is fun!

I recently re-discovered my copy and want to share a couple of the methods with you: the ones that sparked images in my head right away. But check out the method pool on the constructif website (in German, but many of the methods have english titles so you can either guess or google them) for a more comprehensive overview!

Today: methods to start off your lessons

Awaking interest

One idea to start off your lessons is to find something that sparks student interest in the topic you want to discuss. You could for example use quotes, snippets from movies, or provocative statements. These work especially well when students have an easy way to relate to them, for example because they are related to things that are relevant in their own lives or to their future in the profession.

Examples that come to mind:

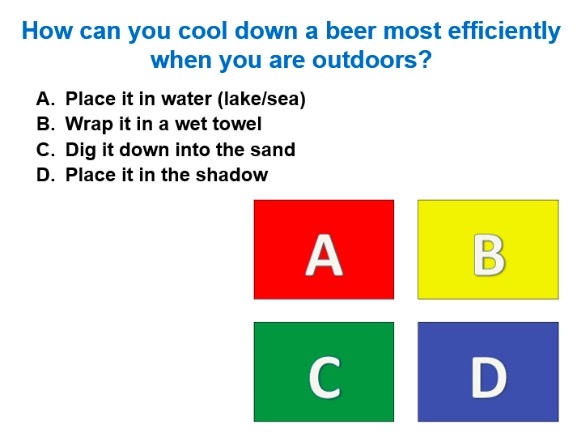

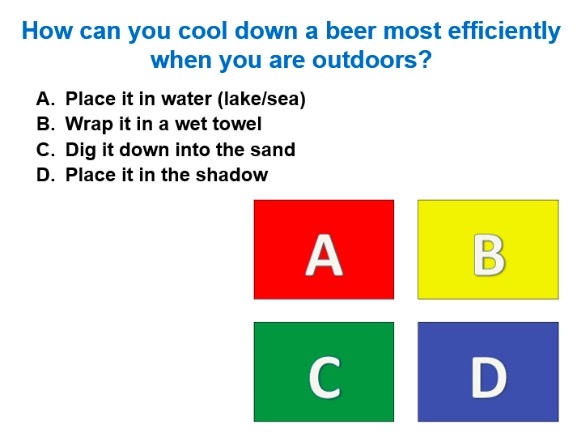

1. A really fun question like Kjersti‘s below: How can you cool down a beer most efficiently when you are outdoors? Isn’t this intriguing even when you have no idea what the lecture is about?

Multiple choice question by Kjersti Daae, used with permission

This can be used as a multiple choice question at the beginning of the class, or just shown then and only picked up again at the end of the class, hopefully inspiring the students to pay attention in order to figure out the answer along the way.

2. Fun memes. I remember starting classes on ocean salinity with one showing a shark and saying something like “Did you know? The ocean is salty because of the tears of misunderstood sharks that just want to play” (tried to find the original source, but there are so many variations of this out there that I couldn’t be sure). Even though it’s probably obvious that this is not the answer we are going for, it still raises the question “why is the ocean salty” in a fun and playful way.

3. Interesting applications. I used to have a picture of a car with its heavy load poking through the front windscreen — it had clearly not been secured properly when the driver suddenly had to brake. Inertia can really be tricky… What’s great about such a picture is that it makes the relevance of an otherwise quite abstract and hard to imagine concept absolutely obvious.

I like having questions and pictures like these up on the screen while students enter the (virtual) room to get them thinking about the upcoming session. If you are really ambitious (in a good way!) you could also rotate through a slide deck with several types of prompts for thought/discussion…

Fast networking

Students interview each other on the topic of the upcoming lesson (maybe there could be an overall question or prompt that they are trying to find information for?) and visualise the results. This activates prior knowledge and, through the visualization bit, also puts different snippets of knowledge into relation with each other.

What’s different from “talk to your neighbour about this for a minute”? The clear roles of interviewer/interviewee facilitate a conversation more easily, especially with students that don’t know each other well and/or are shy.

Living statistics (sometimes also called sociometry)

This is a method that I have used a lot but had forgotten about now that things have been online for me in what feels like forever: asking questions and assigning spaces in the room for different answer options, and have students move around the room to answer them. This method is great when facilitating students getting to know each other, e.g. asking them to place themselves on an imaginary map of where they were born (without too clearly prescribing what is where, so that students need to talk to each other to figure out where to place themselves relative to each other), how much prior knowledge they have, what fields they come from in interdisciplinary courses, … It’s usually easier to remember who stood close by in response to a certain question than to remember everybody that had put their hand up, and especially in large classes where students don’t know each other yet, that is really helpful!

Place mat

For the “place mat” method, three or four students sit around a table together and simultaneously write their thoughts on a given question on a large sheet of paper, each in their own corner. After a while they then compile their thoughts into common notes in the middle of the piece of paper. Those common thoughts are then later shared with the whole group.

I really like this method because I am a big fan of note-taking, both to facilitate individual thinking as well as in group discussions. When I teach virtually, I often use a shared google slides document, in which each group is taking notes on their own slide. This is great for several reasons: a) students take notes so no ideas get lost between when they talk about it and later present it to the large group, b) I can “spy” on the groups’ progress and adjust the length of breakout sessions without interrupting groups by popping in on them, c) I get an idea of what they are discussing and can prepare a strategy for how I want to bring the points from different groups up in the following discussion with the whole group.

That’s it for today! We’ll continue next #TeachingTuesday with “methods to acquire knowledge”!

What other methods do you like for active starts of your lessons?