Currently reading MacInnes et al. (2026) on “Who do we trust on climate change, and why?”

What we believe about climate change often does not depend on what we know about climate change, but on what people around us believe. This makes it really difficult for climate scientists to make their warnings heard and acted upon by people outside their own bubble. In their article “Who do we trust on climate change, and why?”, MacInnes et al. (2026) suggest how to communicate in a way that is perceived as trust-worthy.

I’ve been intrigued in what makes people trust science messages for a long time. Climateoutreach.org, for example, is doing great work on what kind of messages work better than others (for example no polar bears but real people). But I have also been interested in what makes people trust scientists, going back to the work of Hendriks and colleagues. In their model, trust is determined by how competent, benevolent, and integer we perceive someone to be. MacInnes et al. (2026) use a similar model, but they add “communication style and accessibility” (probably the easiest aspect to adapt to target audience to foster trust without losing authenticity!) into the mix. They say that “[a] communicator who uses jargon, speaks opaquely, or dismisses opposing views may be perceived as arrogant or unapproachable, qualities that erode trust”, and that sounds immediately obvious (in our model, Rachel and I might have counted not using jargon, speaking opaquely, or dismissing opposing views as “teaching competence”, but we did split “competence” into “teaching competence” and “subject matter competence” exactly because we felt that they were two different things and should be looked at separately. So this is a different way to do basically the same thing!).

MacInnes et al. (2026) use data from 13 countries, collected in 2023. They compare “believers” and “skeptics” and find that there are different pattern in how trust is formed. While both have a relatively high trust in climate scientists (they are the most trusted source for believers, but still third-most trusted source (out of 14) for skeptics), activists are a lot more trusted by believers than skeptics. Societal leaders (government or business leaders, social media influencers, religious leaders, journalists) are least trusted by believers and a lot more by skeptics (interesting!).

What MacInnes et al. (2026) highlight is that “friends and family” and “people like me” are given a high level of trust across the board of respondents. Especially skeptics seem to rely on relational trust as a proxy for trustworthiness more generally, as well as on “non-dismissiveness” (and they might encounter dismissiveness more than believers, since their views go against the scientific consensus). MacInnes et al. (2026) also point to loyalty and in-group norms to explain their findings of trust in climate scientists, rather than general distrust for skeptics, or trust for believers.

“Academic credentials” are important to 1/3rd of the believers, but only to 1/5 of skeptics. “Other highly valued features of trustworthy messengers (in decreasing order) were that they were easily understandable, did not directly profit, were not dismissive of opposition, had shared values, and spoke passionately.” (“Passion may act as a proxy for intrinsic motivation, suggesting that the communicator cares deeply about the issue and is not simply acting out of self-interest”)

Regarding the trustworthiness of a message, MacInnes et al. (2026) find that “more than half of respondents wanted messengers to supply supporting data and research”.

Implications of this study are that trust does not just depend on what role a communicator holds, but also how they communicate (no surprise here), and that relationships are super important: “trust emerges less from the possession of knowledge and more from the perceived intent, clarity, and cultural closeness of the messenger”. Climate communication should therefore put more effort into dialogue and co-produced engagement, for example through mobilizing trusted lay networks. This could mean engaging “friends and family” and “people like me”, and equipping them as key messengers, for example through training programs, partnerships, tool kits for peer-to-peer engagement, mentoring, etc.. It is also important to focus on communicator credibility and tone: “communicators should be attentive to how they come across; not only as competent, but also as clear, respectful, and authentic”. Specifically, “not being dismissive of opposition, sharing values, and speaking with passion are powerful signals of trustworthiness”. And, importantly, the findings show there can be no one-size-fits-all approach, but that communication and communicator need to fit the target audience.

The focus on relational trust, and especially on not being dismissive (or not “dumförklara”, as the students in our study said in Swedish) fits super well with my evolving understanding of trust and its role in learning. It is interesting to see that the mechanisms between students and teachers seem to be similar to the ones between the public and communicators of climate change information. Trust does not seem to need a one-on-one relationship as we see from parasocial relationships with influencers and other celebrities, but even there there needs to be some sense of “them” caring about “us”. Finding a shared value base with a target audience and starting from that has been recommended in scicomm for a long time, but studies like this one really show the importance of putting in that effort instead of relying on an expert status to do the heavy lifting in trust building!

MacInnes, S., Hornsey, M. J., Bretter, C., Pearson, S., Fielding, K. S., & Bersoff, D. (2026). Who do we trust on climate change, and why? Global Environmental Change, 96, 103096.

Yesterday I managed to leave the office before it got completely dark!

That was important because I really really wanted to take pictures of ice before it disappeared

And lots of fun stuff to see! Like below, where the sea level clearly sank and produced this cool fracture-vulcano thingy [technical term]

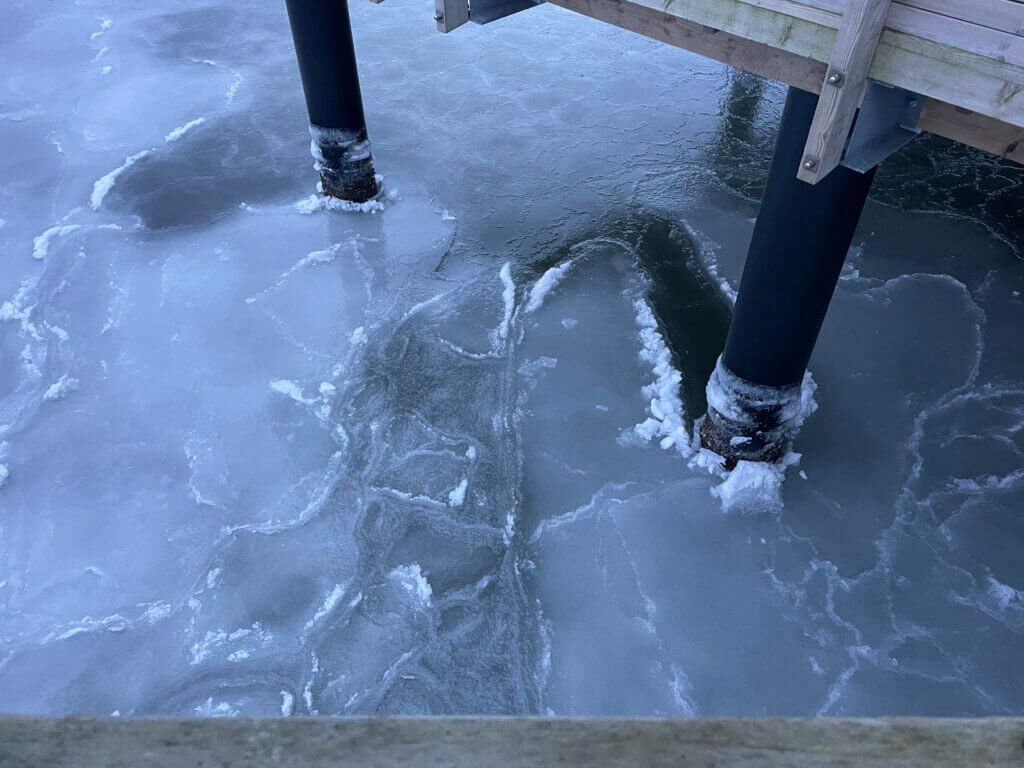

Former and current sea level even more clearly visible here at the ladder and the pillars!

From the other side…

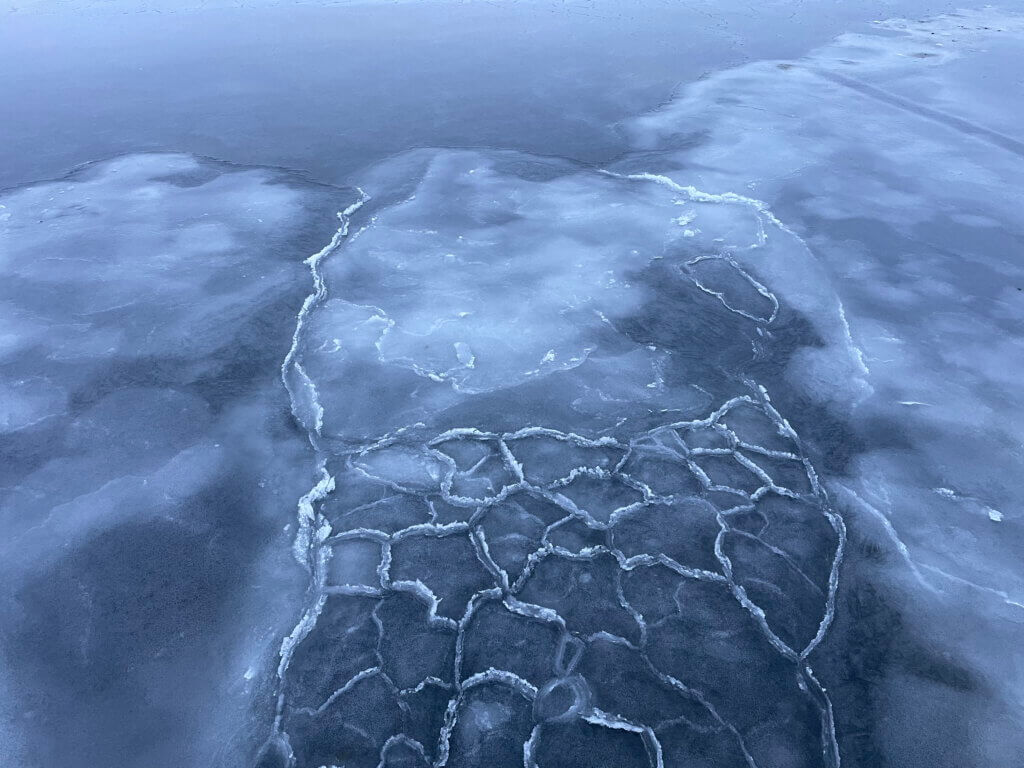

Also cool: a patch of pancake ice frozen into a larger sheet!

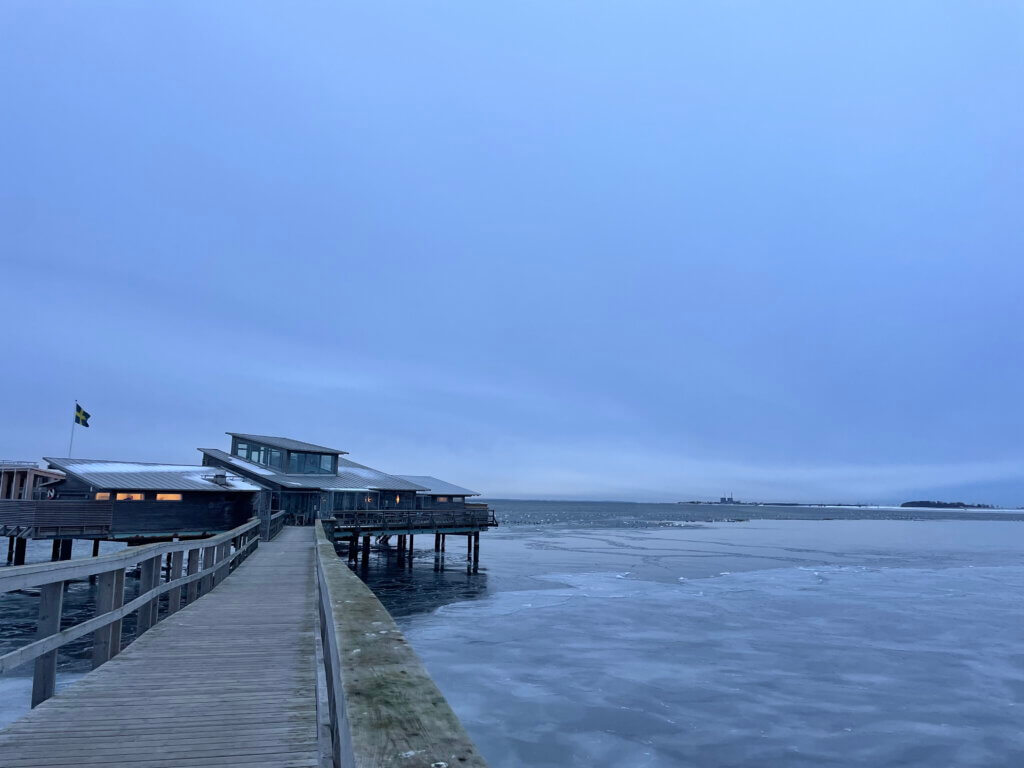

Ice all the way out to the sauna!

And to the bathing stairs

I was tempted to go down and take close-up pictures, but it seems that I learned my lesson last time…

I am glad I went, though!

What you can kinda see below, at least when you know what to look for (but fear not, I am about to tell you!) is that the ice sheet has been drifting upper-right to lower-left. You can see the stripes of broken ice to the left of the pillars!

Close-up of what is going on there…

Now that I had noticed it out on the platform, I could see it almost all the way back to the beach! Here the sheet has been drifting left to right, as you can see from the long stretches of broken ice starting at each pillar and going out to the right

Walking out, my focus was mostly on the other side of the bridge where the ice is still intact. I had noticed one or two of those broken stripes, but attributed them to birds or something during freezing. How wrong was I :-D