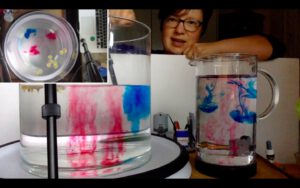

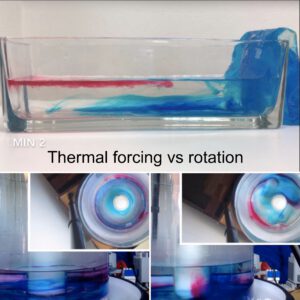

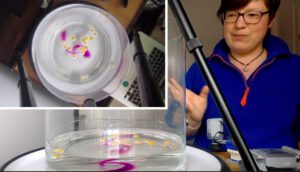

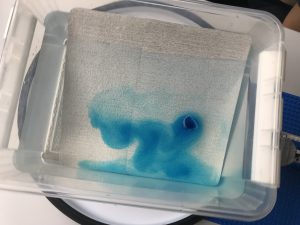

Throwback to the pandemic and teaching from home: “An ocean in a bucket”

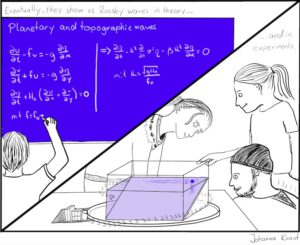

I had completely forgotten about a video that Kjersti and I produced in 2021 to prepare her students for rotating tank experiments by addressing a common misconception before they ever…