Thinking about citizen- and active student participation, inspired by Arnstein (1969), Varwell (2022), Biesta (2026), and others

Since listening to Gerry’s defense of his PhD thesis the other day, I have been thinking about partnership a lot, and how we need to practice partnership also in order to practice democracy. And I vaguely remembered having seen an article where the typical “ladder” is wrapped into a circle, so that rather than being the opposite ends of a spectrum, the lowest and highest levels of participation become neighbors between which one can transition. I found that paper (Varwell, 2022), but in order to really make sense of it, had to go back to Arnstein (1969)’s “ladder of citizen participation”. And I realized that this is really relevant for “teaching through sustainability” (or possibly even for?) in our upcoming MOOC!

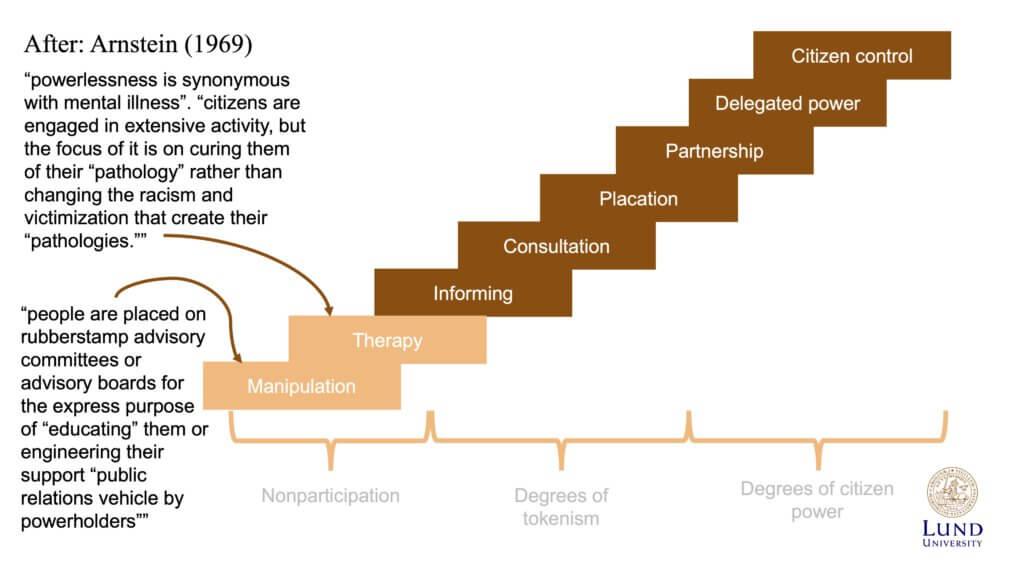

But let’s start at the beginning. Arnstein (1969)’s ladder of citizen participation is a typology that classifies different ways of involving people into decision making. It is not from an educational context and also from a different time, but it is nevertheless interesting to consider for us, as it has been used as inspiration for work in education later. In Arnstein (1969)’s ladder, there are three main degrees of participation: Nonparticipation, degrees of tokenism, and then finally degrees of citizen power.

The bottom two steps in the Arnstein (1969) ladder in the area of nonparticipation, therapy and manipulation, are described as “powerlessness is synonymous with mental illness”, so on this step, “citizens are engaged in extensive activity, but the focus of it is on curing them of their “pathology” rather than changing the racism and victimization that create their “pathologies.”” And at Arnstein (1969)’s “manipulation” step, “people are placed on rubberstamp advisory committees or advisory boards for the express purpose of “educating” them or engineering their support “public relations vehicle by powerholders””. After that, higher steps are about gradually more inclusion into decision making until finally, citizens take control.

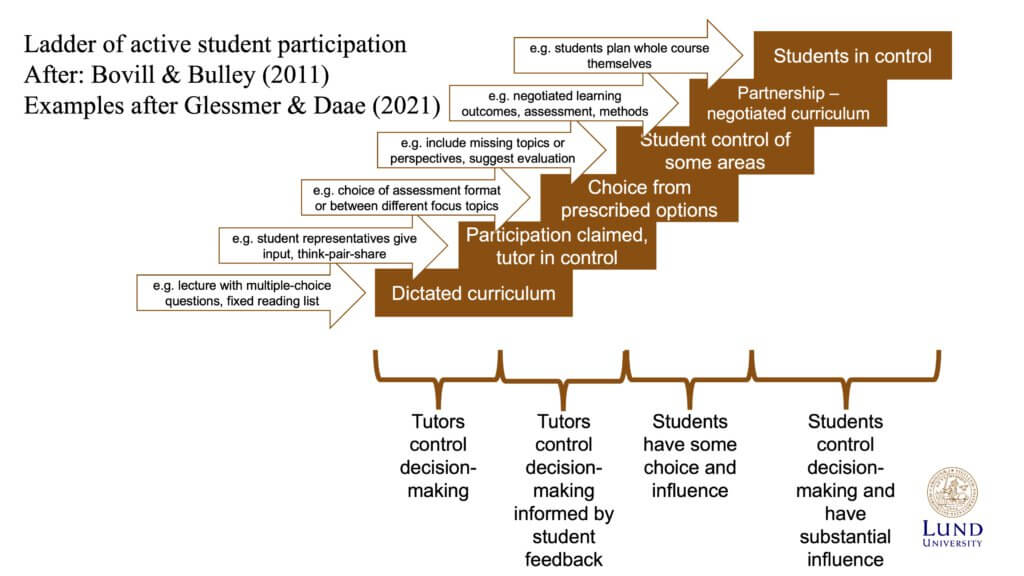

This ladder — minus the two bottom steps, because we would hope that they don’t exist in teaching — is often used in different variations as inspiration to describe active student participation (note my recent blogpost on problems with that if participation is interpreted as taking up airtime, not also quietly engaging with texts etc), for example in Bovill & Bulley (2011). Kjersti and I have adopted their ladder for our own work, and here we have added lots of examples for what each step could mean in practice. For example, where the teacher controls an active learning scenario, they might include multiple-choice questions, or think-pair-shares. Whereas when students gradually take on responsibility, they become involved in planning, facilitating, evaluating a class. In the image below, I changed Arnstein’s labels to the equivalents in education that are commonly used, but the steps are basically the same.

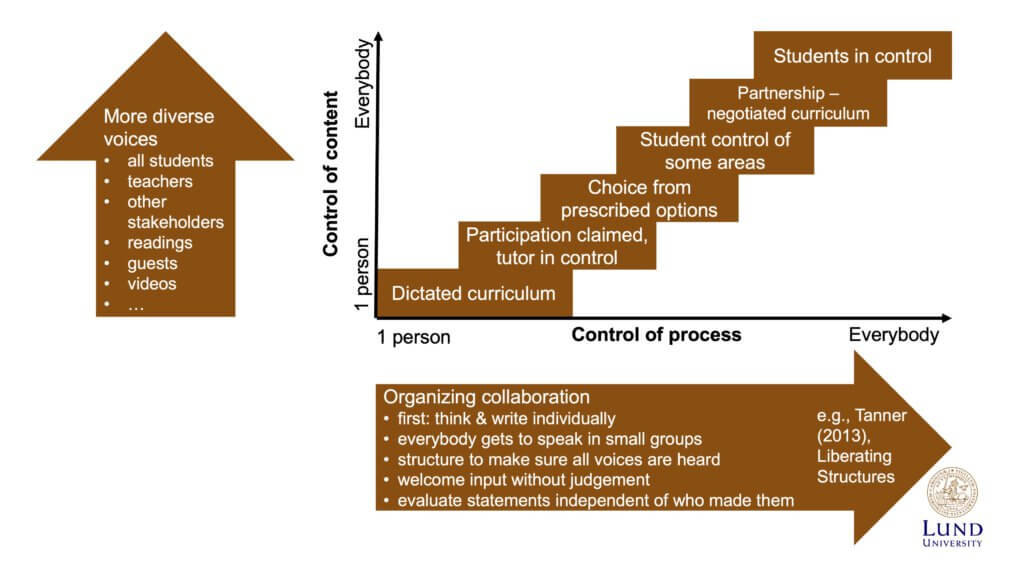

Lately, I have started adding the axes “control of content” and “control of process”, each running from 1 person (usually the teacher) to “everybody” (meaning teacher and all students in the classroom, or all stakeholders in curriculum design. One interesting question is, of course, who gets involved and who does not, and one interesting finding of Gerry’s PhD thesis is that paying students for their involvement in partnership outside of regular class time can really be what enables them to participate). Typically, but not necessarily, as students take more control of the process, they also take more control of the content. These axes seem to be useful when discussing student participation because they make it more obvious that there are different aspects of learning that students can be actively involved in.

If we want to move towards shared control of content, towards more diverse voices being heard, we can do that not only by making sure that all students are heard, but additionally by bringing in other voices that would otherwise not be represented, for example through other teachers, guests, or if we don’t have access to people that can join us physically or virtually, by making sure we offer a wide variety of readings from authors that are diverse in opinions, but also markers like gender, discipline, geography, etc.. To enable more student control of the process, we can make sure that we organize collaboration accordingly. There are great ideas in the liberating structures collection, in Tanner (2013), and in many other places, but in a nutshell:

- first: think & write individually

- everybody gets to speak in small groups

- structure to make sure all voices are heard

- welcome input without judgement

- evaluate statements independent of who made them

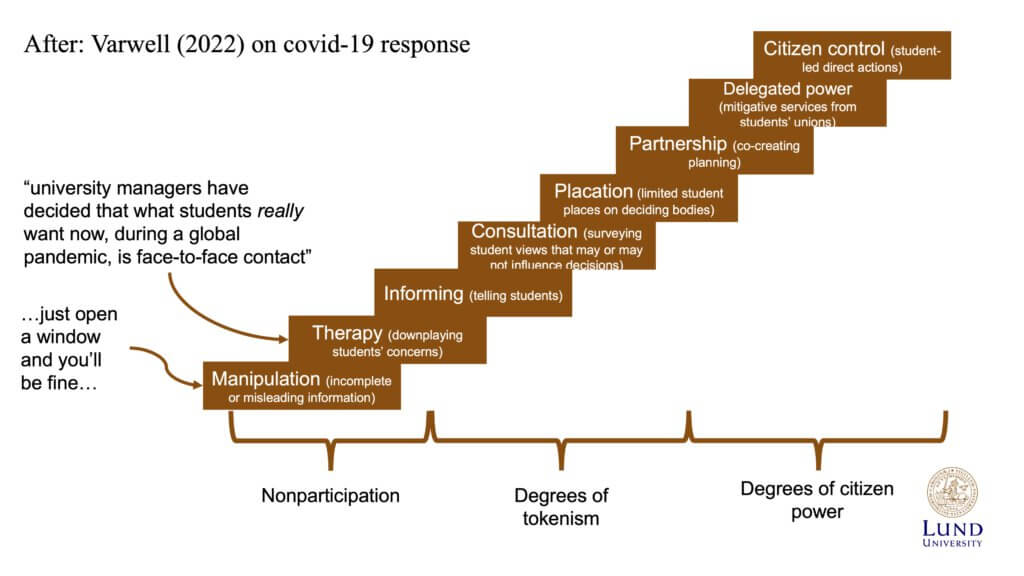

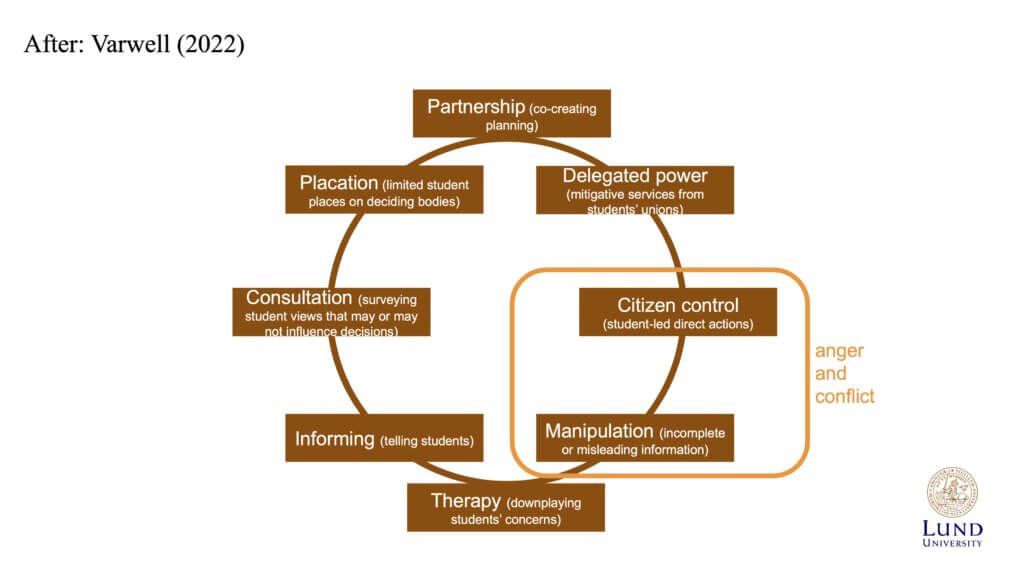

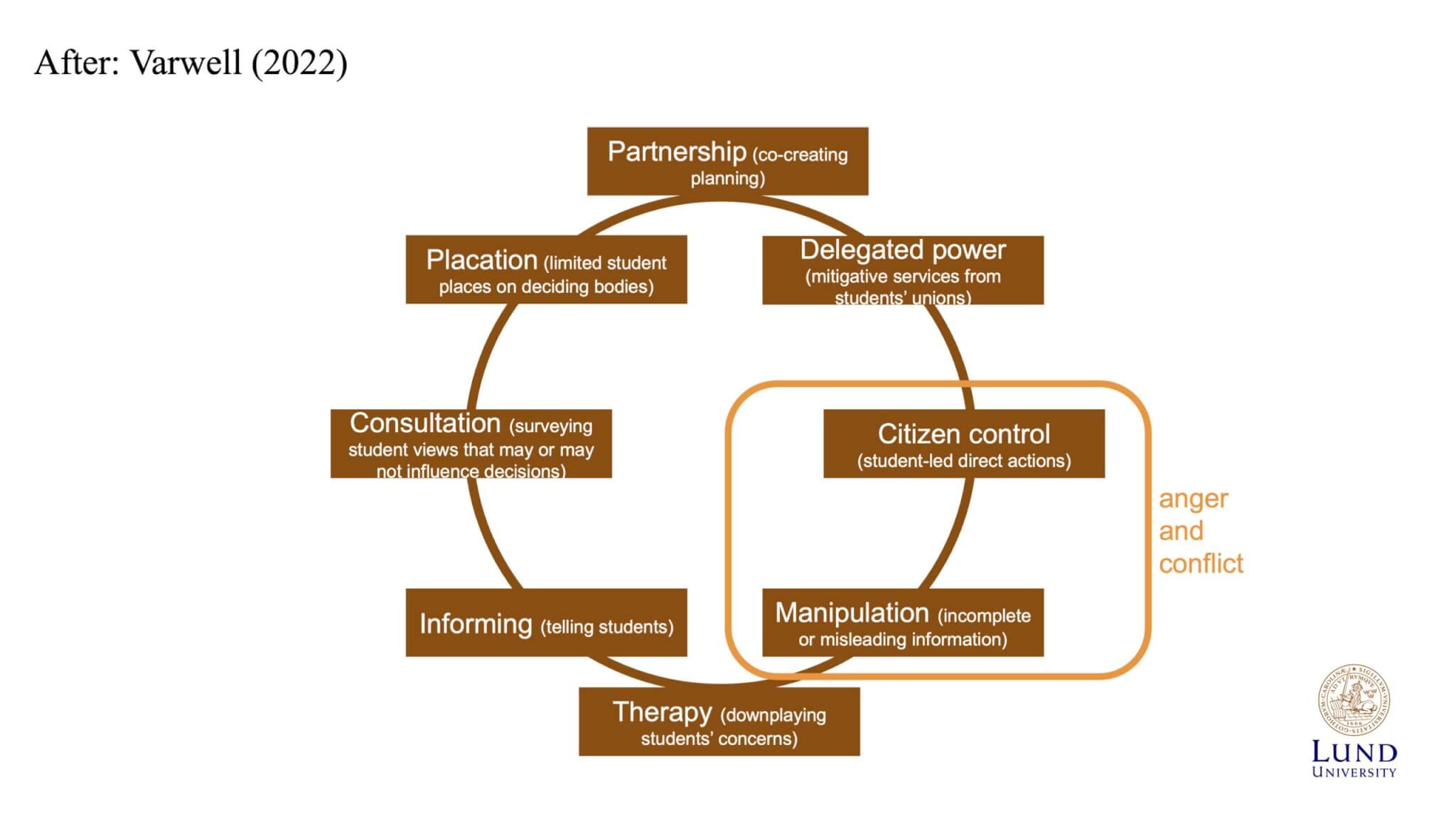

In 2022 in the context of a global pandemic, Varwell brought back the original ladder including the bottom two steps, because it turns out that they do exist in an education after all (see image below for the education-related descriptions of Arnstein’s original labels). These steps are about not taking student concerns seriously and some decision makers making decisions about “what students really want” without actually working with students on that. And that also happens outside of a pandemic, me thinks…

Arnstein’s “therapy” step could, in sustainability teaching, correspond to not taking student concerns seriously, and recommending mental health interventions to “fix” them. Mental health support, I haste to add, is an important part of what students, and we all, should do to cope with the world! The problem here is if we don’t actually take the concerns seriously and help students to find agency in the world, but only recommend they take up yoga or mindfulness meditations, instead of working with them to build agency to actually do something constructive to also fix the root of the problem, not only the symptoms.

Also the “manipulation” step could happen in sustainability teaching: this is where we talk about sustainability, but only as a shallow tick-box exercise and not engaging with student concerns or interests.

Varwell (2022) then reimagined the ladder to form a circle, which brings “manipulation” and “citizen control” right next to each other, in a tension that he lables as “anger and conflict“, and descibes that non-participation can quickly turn into direct action, closing the loop of citizen/student participation. And I can imagine how feeling manipulated and not taken seriously can be a powerful motivator for taking control! He writes that “Specifically at a time of crisis, therefore, there can and must be a model of partnership which is distinct from both the disenfranchised and unengaged citizen-student and the angry and potentially unrepresentative student activist, and which stops the former from converting rapidly to the latter” (and that is not to say that direct action is bad at all! But if we are going for partnership in teaching, we would hope that any direct action being prompted also happens in partnership, not without us…). He was talking about the crisis of the pandemic, but I would argue that we are in a sustainability crisis, so this model works in that context, too.

I feel like this circular visualization of the ladder makes it easier to discuss what kind of partnership we are going for. The conventional ladder evokes the idea that higher up on the ladder is better, but here we can see that if we want true partnership, to support students to be active citizens in a democratic society, we as teachers still have an important role to play, and one that involves negotiation with students. In a 2026 interview with Gerd Biesta, he says “Teaching is about being given what you were not looking for, something you did not even know you could ask for”. Tashdjian summarizes their discussion

“Democracy asks something of us,” Biesta explains. “It runs against pure self-interest or simply doing whatever we want.” He describes this not as a flaw, but as a “valuable difficulty” that makes living together possible. Education, then, should not aim to remove this difficulty. It should help students recognise why it exists and why it matters.

And this is where my on research interest, trust, comes in: The only way we are abloe to negotiate and work through those valuable difficulties is if we have built trust first.

Note: Even though there are LU logos on the images above, this is still my personal blog… I am just preparing these slides for a future presentation and writing through my thoughts here to sort them…

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of planners, 35(4), 216-224.

Bovill, C., & Bulley, C. J. (2011). A model of active student participation in curriculum design: exploring desirability and possibility. In: Rust, C. (ed.) Improving Student Learning (ISL) 18: Global Theories and Local Practices: Institutional, Disciplinary and Cultural Variations. Oxford Brookes University: Oxford, 176-188.

Varwell, S. (2022). Partnership in pandemic: Re-imagining Arnstein’s ladder of citizen participation for an era of emergency decision-making. The Journal of Educational Innovation, Partnership and Change, 8(1).