I’m still inspired by Cathy’s work on “co-creation”, and an episode of “Lecture Breakers” (I think the first one on student engagement techniques where they talked about letting students choose the format of the artefact they do for assessment purposes; but I binge-listened, and honestly, they are all inspiring!). And something that Sam recently said stuck with me — sometimes the teacher and the students just have “to play the game”. Assessment is something that needs to happen, and there are certain rules around it that need to be followed, but there are also a lot of things that can be negotiated to come to a consensus that works for everybody. So, as a teacher, just be open about your role in the game and the rules you yourself are bound by and the ones you are open to negotiate, and then start discussing! Anyway, the combination of those three inputs gave me an idea that I would like your feedback on.

Consider you want to teach a certain topic. Traditionally you would ask students to do a certain activity. You have specific learning outcomes you want your students to reach. Whether or not they reach those outcomes, you would evaluate by asking a certain set of questions to see whether they answer them correctly, or maybe by asking them to produce an artefact like an essay or a lab report. And that would be it.

But now consider you tell students that there is this specific topic you want to teach (and why you want to teach it, how it relates to the bigger picture of the discipline and what makes it relevant. Or you could even ask them to figure that out themselves!) and that they will be free to produce any kind of artefact or performance they want for the assessment. Now you could share your learning outcomes and tell them about what learning outcomes matter most to you, and why. And then you could start discussing. Do students agree on the relative importance of learning outcomes that you show in the way you are weighing them? Are there other learning outcomes that they see as relevant that you did not include (yet)?

Once that is settled (possibly by voting, or maybe also coming to a consensus in a discussion, depending on your group and your relationship to them. And of course you can set the boundary conditions that maybe some learning outcomes need to count for at least, or not more, a certain threshold), you are ready for the next important discussion. How could students show that they have mastered a learning outcome? What kind of evidence would they have to produce? What might count as having met the outcome, what would still count as “good enough”?

Now that it’s clear what the learning outcomes are and what they mean in terms of specific skills that will need to be demonstrated, you could let students add one learning outcome that they define themselves and that is related to the format of the artefact that they want to produce (possibly public speaking with confidence when presenting the product, learning to use some software to visualise, or analysing a different dataset than you gave them themselves, …). You could have already included 10% (or however much you think that skill should “be worth”) in the rubric, or negotiate it with students.

While negotiating learning outcomes, students will already have needed to think about how each learning outcome will become visible with their chosen way of presentation, and this should be talked through with you beforehand and/or documented in a meta document, so that a very artistic presentation does not obscure that actual learning has taken place.

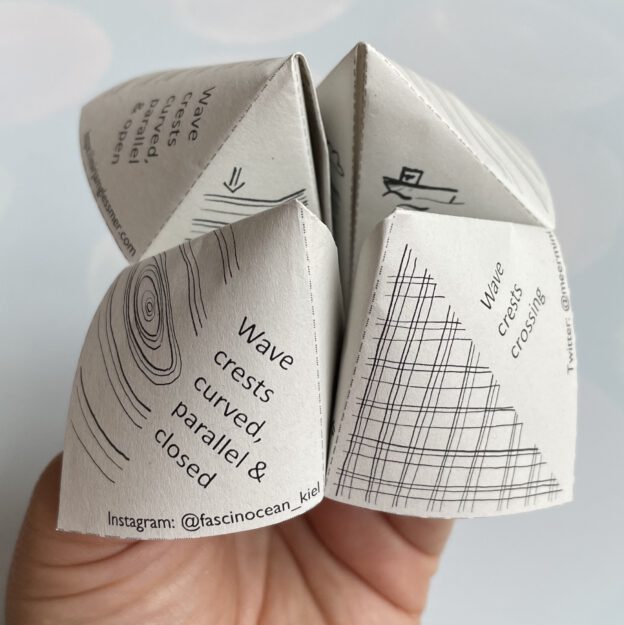

How much fun would it be when people can choose to give a talk, do a short video, present a poster, design an infographic, rhyme a science poem, or whatever else they might like? I imagine it would be super motivating. Plus it would help students build a portfolio that shows their subject-specific skills acquired in our class alongside other skills that they think are fun or important to develop. And maybe some artefacts could be used in science communication, engaging other people by hooking them via a format they are interested in, and then maybe they also get interested in the content? I’ve seen hugely creative ideas when we asked students to write blog posts about phenomena we had investigated in the rotating DIYnamics tanks, like a Romeo-and-Juliet-type short novel on two water drops, or an amazing comic — and there they were confined to writing. What if they could also choose to make objects like my pocket wave watching guide, or to perform a play?

I guess it could be overwhelming when the content is very difficult, the task is very big, and students then also have to consider how to show that they learned it, in a way that isn’t pre-determined. Also timing might be important here so this task does not happen at the same time as other deadlines or exams. And obviously when you suggest this to your students, they might still all want to pick the same, or at least a traditional, format, and you would have to be ok with this if you take them seriously in these negotiations. What do you think? What should we consider and look out for when trying to implement something like this?