I’ve been fascinated by gooselings recently, mainly because they are super cute. But I can tell you about what makes wave watching special when the waves are made by geese — it is an extra challenging type of wave watching! (Check out this post for a more general — and likely much more useful — guide to wave watching)

I dug through my phone (all these pictures are from this year, but they aren’t posted chronologically as you’ll see from the size of the gooselings) and found quite a collection. This is for you, Yasmin and Maike!

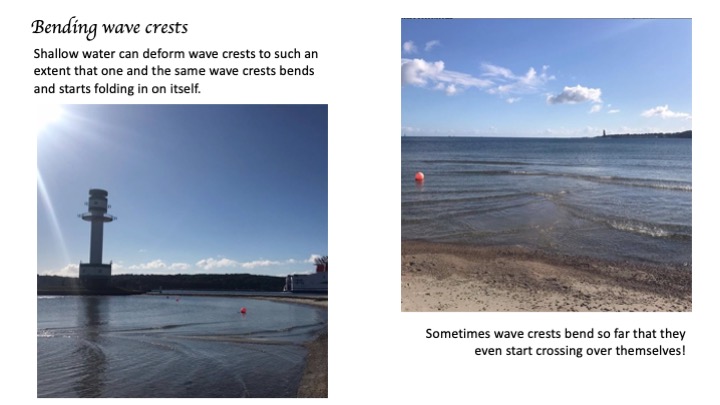

Let’s start out with a couple of pics that work well for wave watching purposes, but that already show hints of the challenges discussed below.

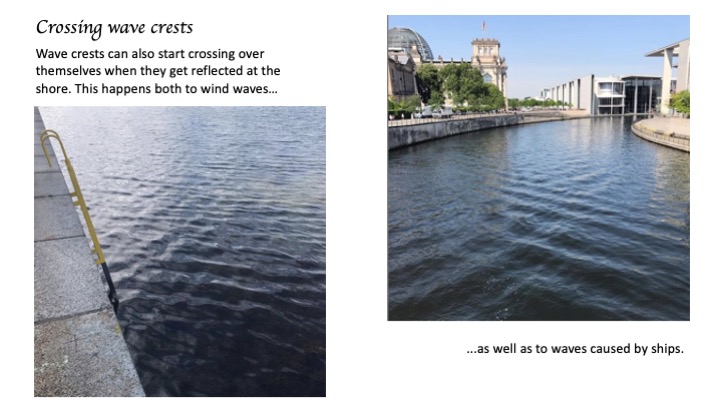

Here all three gooselings and the goose that is still closer to the shore are swimming fast and are making beautiful wakes; those feathery, V-shaped waves that are caused by them swimming faster than the speed at which waves can spread. The goose swimming in the front is swimming slower than that critical speed: See how there is a wave the goose is pushing in front of itself, but how it doesn’t break into these feathery structures? And the background wave field, those large curved waves, were likely caused when one of the large geese jumped into the water, or at least something close to the lower left corner of the picture falling at about the time it would have taken the front goose to swim to where it is now at a slow (but typical) speed.

And here, the geese are doing what I’m always hoping I’ll snap a good picture of: Swimming exactly in a row. This should be energetically really good, because the goose swimming in front already creates the wake and lowers the resistance for all the other geese swimming in its wake. You see that both families are doing it in this pic, but then the duck still takes the price for the prettiest wake.

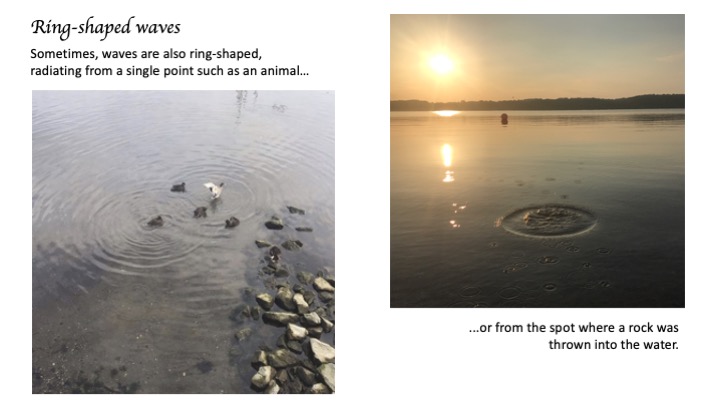

Here is another example of the front goose doing the hard work and the gooselings following in its wake. For some reason, geese never have such nice distinct wakes as ducks! Maybe it’s their bow shape in addition to their erratic swimming behaviour?

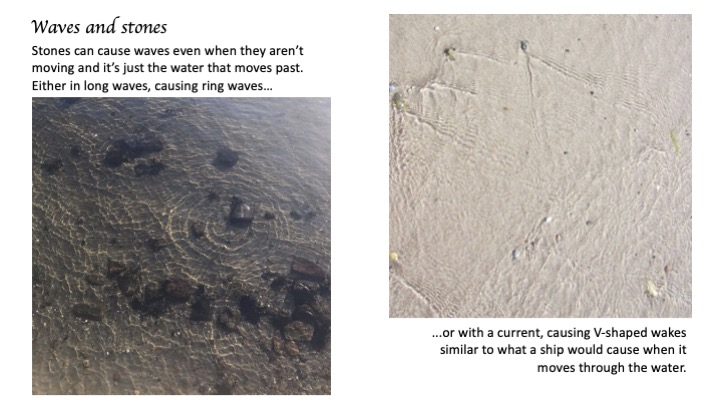

This picture gives you a glimpse of the problems we are about to discuss below. See the resting gooselings on the tree trunk in the right? Cute, but not helpful for wave watching. And the ones that are swiming, although making comparatively pretty waves, are changing speed and direction so much that the wave field looks quite messy. You can see they all started out fom the left side of the partly submerged tree trunk (the one the other family is sitting on on the right)

Here again: They CAN make petty waves if they choose to, but they are often moving quite erratically. Speeding up, slowing down, changing direction… But the right family is making pretty waves!

So why is it so difficult to get good pictures of geese-made waves? Continue reading