How to adapt the same experiment to different levels of prior knowledge.

In this post, I presented an experiment that I have run in a primary school, with high-school pupils, in a Bachelor-level course and in a Master-level course. The experiment itself was run identically in all cases. However, the introductions, explanations and discussions about it obviously differed.

For example, in the primary school, I introduced this experiment by showing pictures of lions and penguins and other animals that the pupils knew live in warm or cold climates, and we talked about where those animals live. In the end this aimed at how temperatures are a lot colder at the poles than at the equator. This is the differential heating we need for this experiment to work. While this is something that I felt the need to talk about with the primary school kids, this can be assumed as a given with older students (or at least that is the assumption that I made).

With the university-level courses, one of the points that I made sure came up during the discussion are the limitations of this model. For example that we apply both heating and cooling over the full depth of the water column. How realistic is that? Or the fact that we heat at one end and cool at the other, rather than cooling on either end and heating in the middle?

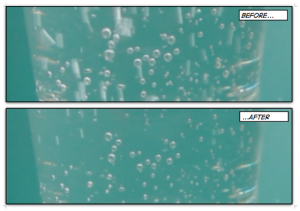

With the university-level courses, we could also discuss other features that we could see during the experiment. Remember this image, for example?

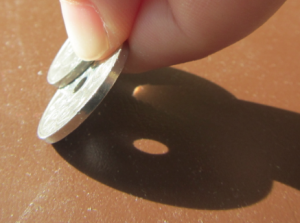

The thermal conveyor belt experiment.

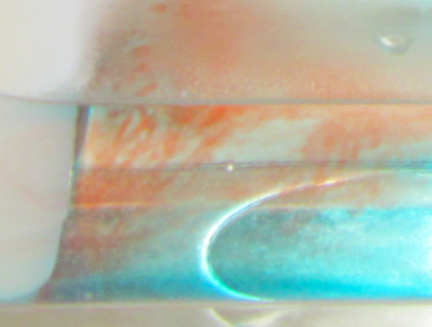

Let me zoom in on something.

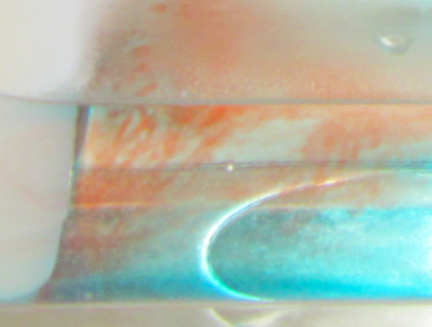

Curious features in the thermal conveyor experiment. Do you know what this is about?

Do you see these weird red filaments? Do you think they are a realistic part of the thermal circulation if it was scaled up to a global scale?

Of course not. What we see here is salt fingering (oh, and did you guys notice that a diagram of how salt fingering works is displayed at the very top left of my header? I wasn’t exaggerating when I said that it was my favorite process ever!). So basically, this is a process that is caused by the different diffusivities of heat and of the red dye. And while it is pretty large scale in our small tank, you cannot scale it up just like that when talking about the real ocean. And it is also really difficult to get rid of salt fingers for this experiment, in fact I haven’t yet managed. But I am open to suggestions! :-)

Another point that I would talk about with university-level students that I would probably not bring up with primary school kids (- although, why not if I had more time than just those 45 minutes per class?) is that ocean circulation is driven by more than just differential heating. Even when just considering the density-driven circulation, that is additionally influenced by changes in salinity. Put that together with wind-driven circulation and we are starting to talk about a whole new level of complicated…

But anyway. My point is that even primary school kids can benefit from doing this kind of experiments, even if what they take away from the experiments is not exactly the same as what older students would take away.

One of the main messages the primary school kids got seems to have been that you need to take curd cheese beakers for your warming element (look here for some reports (in german)). Not exactly my main message, but at least they were very observant of how the experimental setup was designed ;-)