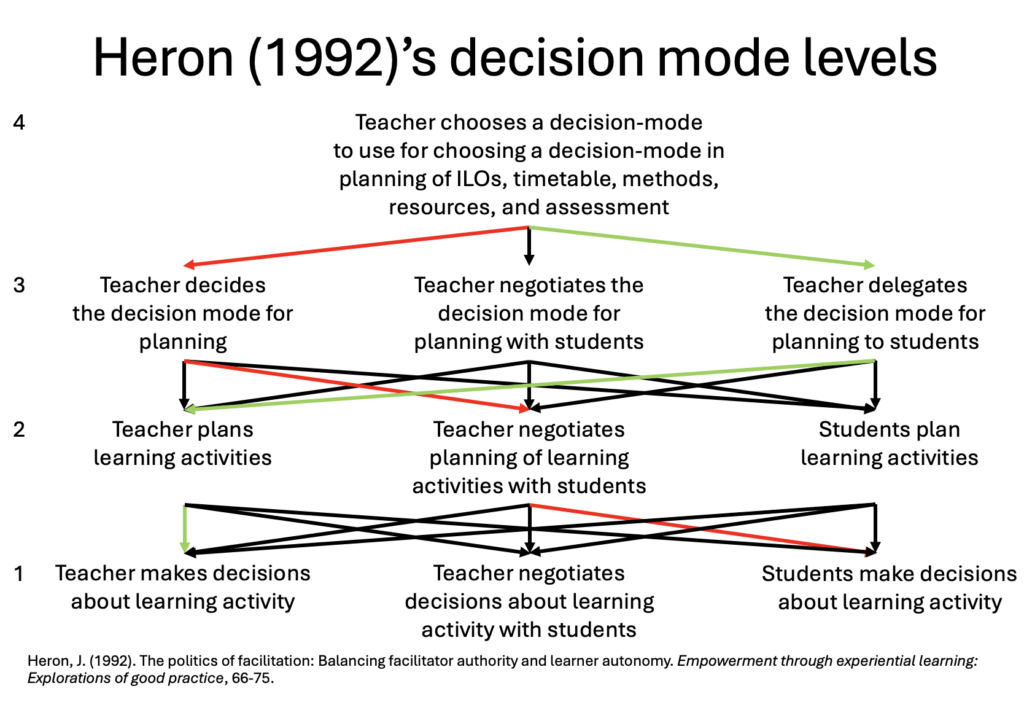

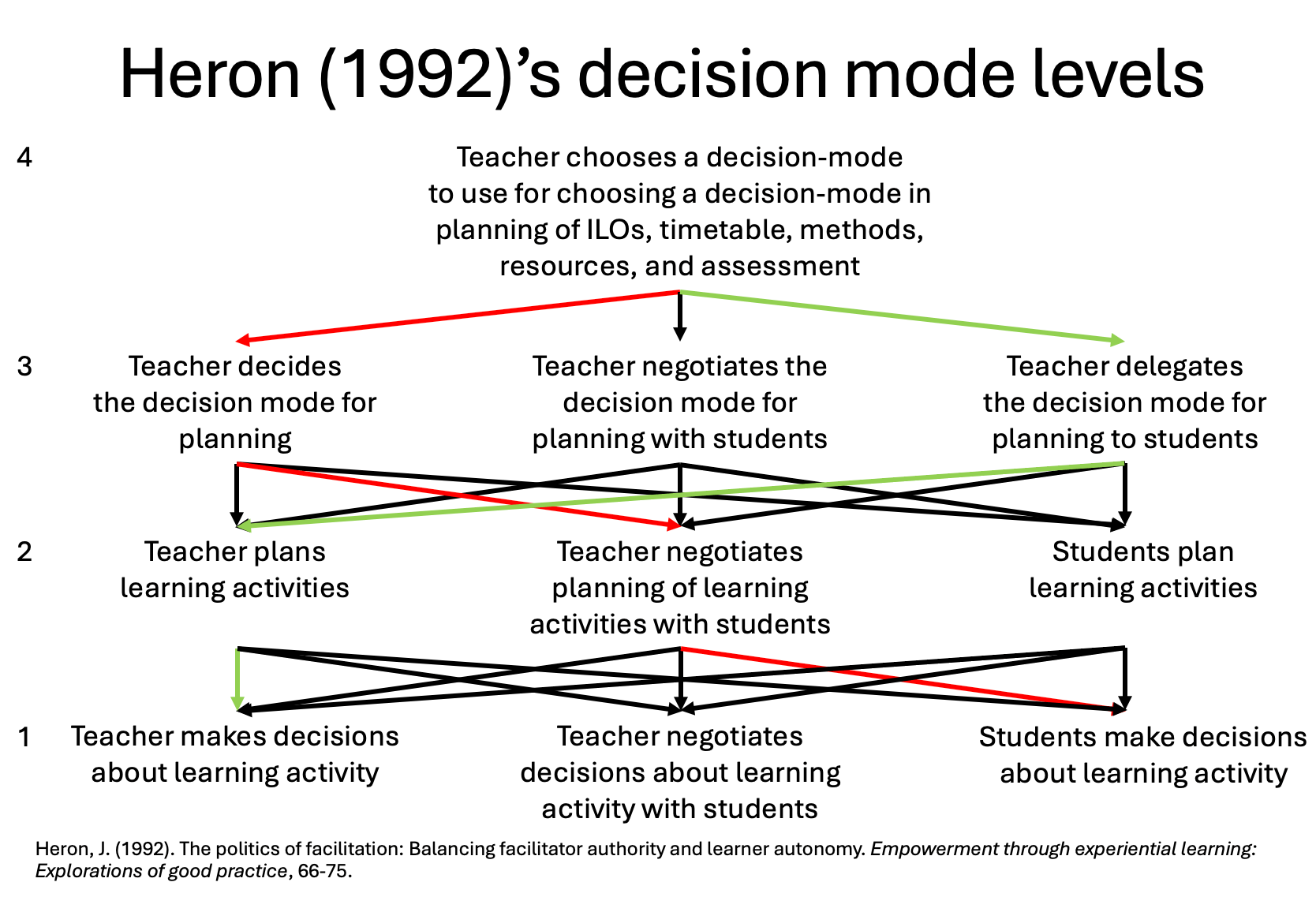

On all the levels of decision making when sharing responsibility for learning (after Heron, 1992)

I have been thinking a lot about how we want to share responsibility when co-creating, responsibility for what, and sharing with whom, and then Cathy recommended the Heron (1992) chapter “The politics of facilitation: Balancing facilitator authority and learner autonomy”, and suddenly I have a super helpful framework to think about these things!

Heron (1992) distinguishes three types of authority that a facilitator (or teacher) holds:

- Cognitive authority is about the knowledge and skills that the teacher has

- Political authority is about taking decisions regarding the content and process of learning

- Charismatic authority is about being a role model in how to act in the role

We know that people learn best when they take on responsibility for their learning and are involved in shaping what, when, how to learn. So there is a bit of a tension between “classical teaching”, using political authority to make decisions about content and process, charismatic authority to model and punish, and cognitive authority to talk about content, on the one hand, and on the other giving learners autonomy to direct their learning. But if we give all the control to the learners, then why still have a teacher? How can we navigate this tension?

Heron (1992) develops a “model of teaching as initiation into autonomous and whole personhood”. In that model, cognitive authority is dialled back so the teacher is more of a facilitator or consultant. Charismatic authority then means “emanating respect for the autonomy and wholeness of learners through a tone of voice, timing, behavioural manner, as well as choice of ideas and language, so that these things also elicit the emergence of such autonomy and wholeness – at all times”. But political authority is the most interesting aspect, where the teacher goes from making all the decisions to only deciding on one of three decision-making modes (direction: the teacher makes decisions for the students; negotiation: the teacher makes decisions with the students; delegation: the teacher lets the students make decisions) in the five areas of the intended learning outcomes, the schedule, the methods, the resources, and the assessment. The teacher thus controls the degree and pacing of empowerment.

This happens on four levels: The activity itself, the planning of the activity, the planning of who is planning the activity, and at the 4th level, where the teacher needs to make the decision to make a decision about all the levels below. I have re-imagined the Heron (1992) figure where this is illustrated (see below).

In the figure, you can take many different paths depending on the decisions you make at different levels (and, actually, this should be a lot more complicated, since this tree can be done in different ways for each of the five areas of educational decisions mentioned above!). But just for illustrative purposes: In the red case, a teacher decides that they want to make decisions about learning activities in negotiation with students, and the outcome of these negotiation is that students take full responsibility for the learning activity. In the green, maybe less likely, case, the teacher decides to delegate all decision-making about the planning to the students, who in turn decide that the teacher should do the planning, and also make all decisions in the learning activity.

But the main point is that these decisions happen on many different levels, and that students can be involved on one, two, or three of them, depending on how reflected the teacher is and if they start on level 4, 3, 2, or 1.

To me, this is a super useful framework to think about co-creation, and how much responsibility I want to share. One thing that I think needs more thought here is “the students”. Who are they? In my recent review of the Lowe (2023) book, I mention some barriers to student involvement, like caring responsibilities, missing social capital, lack of confidence, or immigration status that prevents employment. But assuming we get rid of those barriers somehow, even the method how we include students itself determines how many students ARE included, for example using focus groups or student representatives does not include ALL students. Which, if our goal is a democratic university, we should aim for. So how can I bring these thoughts above together with the ideas behind Liberating Structures? Stay tuned, I will think about that! :-)

Heron, J. (1992). The politics of facilitation: Balancing facilitator authority and learner autonomy. Empowerment through experiential learning: Explorations of good practice, 66-75.