Recap of the first meeting of my new course “Teaching for Sustainability”

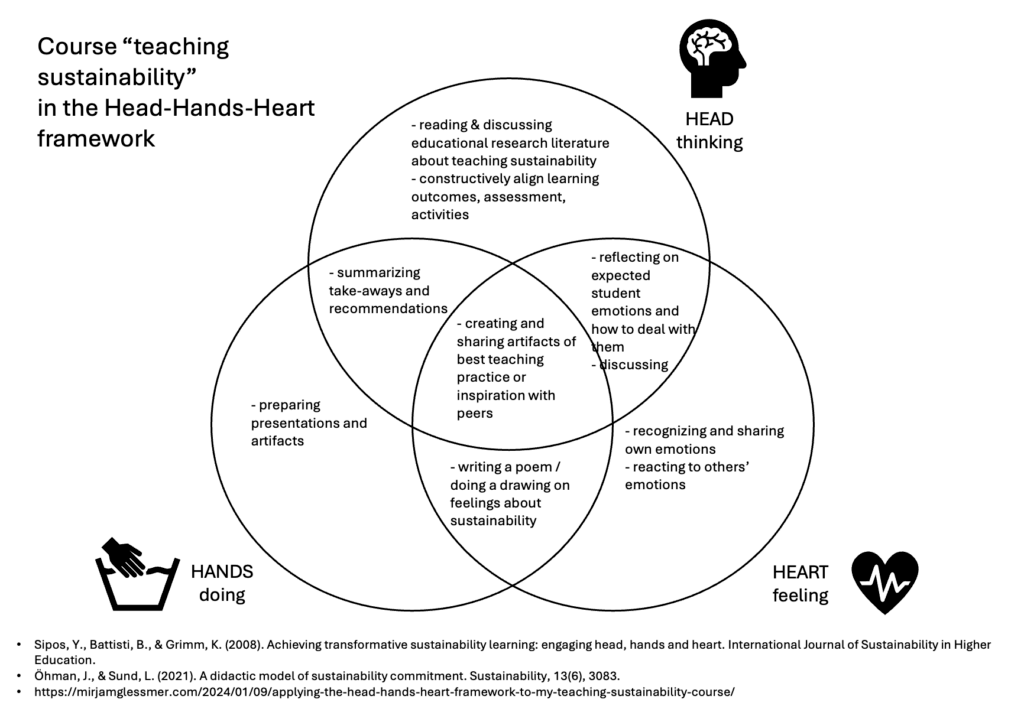

Yesterday was the first meeting of this spring’s installment of my “teaching for sustainability” course and it is so inspiring and energizing to meet so many motivated and engaged teachers! Here is what we did.

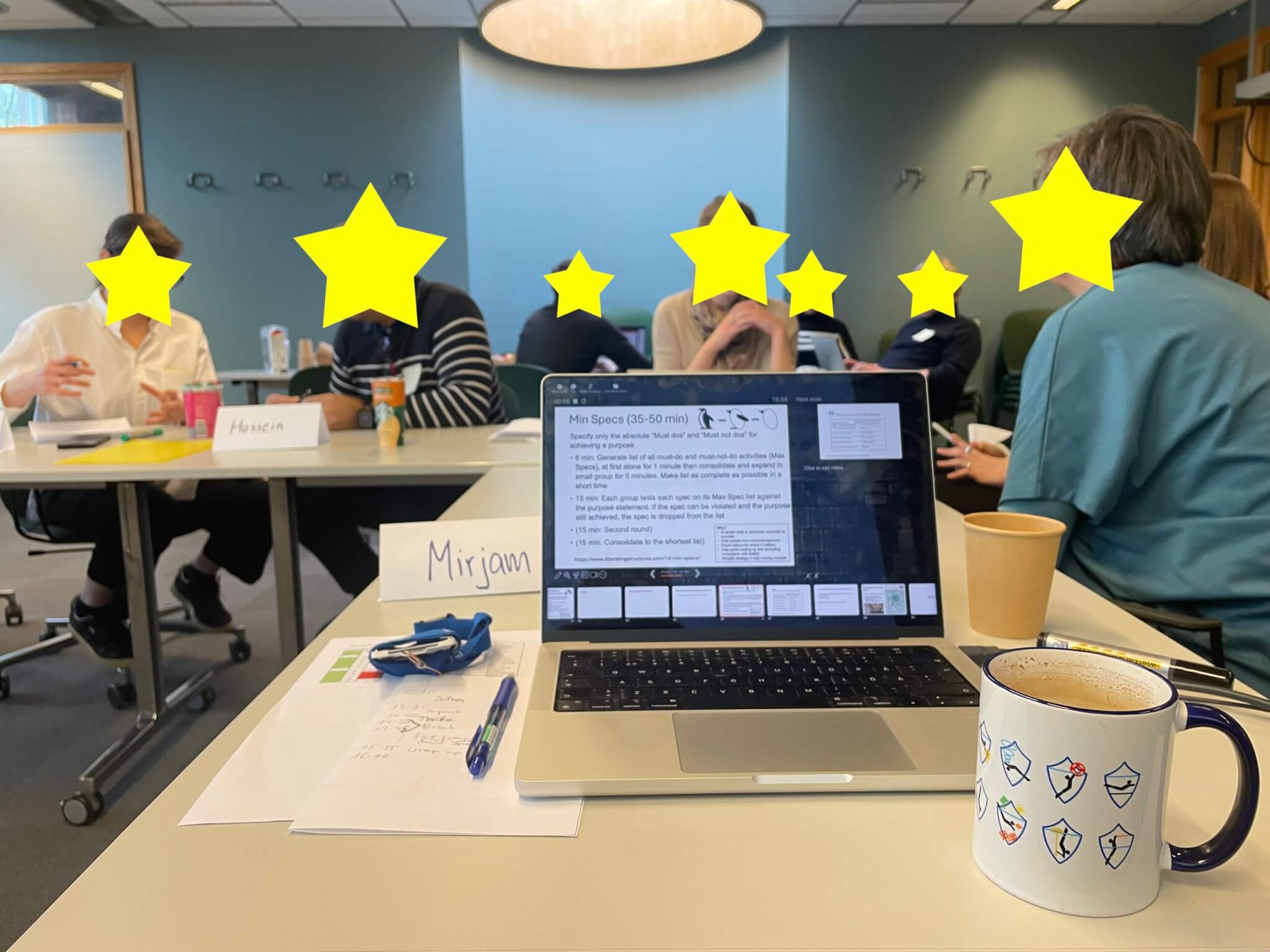

We started out with “impromptu networking” (see figure below for instructions) so each participant got to speak to three others for a couple of minutes each. In our context, this is an unconventional way to start, but I loved observing how quickly the conversations developed between people that mostly did not know each other before entering the room. It feels interesting to not have a classical introduction round, going clockwise around the room, where everybody says something, but the idea with the impromptu networking method is to give opportunity for many parallel connections to be formed, but also to help people figure out what they are hoping to get from a meeting and what they can contribute themselves, by taking about it with three different people. And maybe people even got ideas for their own teaching already now? Impromptu networking is one of the liberating structures, designed for “including and unleashing everyone”.

After this, I already felt very comfortable with the group — seeing everybody engaging in a positive way is so reassuring for any teacher ;-) — and I hope the same held for everybody else. So now I presented my own goals for the course:

- Participants work on a project of their choice. It should ideally be useful for other teachers, too, but it has to be something that they think will improve their own teaching

- I want participants (and myself, hence this post) to create artifacts of our learning in this course that we can share with others

- I hope participants will grow their supportive network and find inspiration!

The course is designed to support these goals:

- In the first meeting (which I am describing in this blog post), participants get to know each other, we talk about Teaching for Sustainability on a general level, participants articulate the topics they are interested in, find themselves together in groups, and start working on defining their projects

- Between meetings, participants individually find, read, and summarize an article which is relevant to their project, and they meet up with another teacher from outside the course to either observe them teaching for sustainability, or to have an “inspirational fika” with them where they talk about it, and which they report on in writing

- In the second meeting, we share experiences, ideas, inspiration from the literature and conversations, and groups really buckle down and start working on their projects

- Between meetings, the groups work on their projects. They submit a draft, read each other’s draft and prepare feedback

- In the third meeting, we do peer feedback and more working on the projects

- Between meetings, groups get input from a “critical friend” (read more about that role here), and prepare a presentation

- The fourth meeting is open to interested colleagues from across Lund University, and here we present the projects! I’ll explain my reasoning for organizing the meeting that way below.

- Then participants submit a report and get two weeks of credit

Now with this out of the way, let’s talk about sustainability! (Actually, what a teacher-centered way of thinking. Participants did talk about sustainability to each other before, it’s just that I did not…)

Anyway, I started out talking about how it’s a bit of a trap to try to define what “sustainability” actually means (see Block & Paredis (2019)’ second misunderstanding), while also raising that we need to think not just about ecological concerns (see Block & Paredis (2019)’ first misunderstanding), but also about economical and societal, and also make this clear to our students. And that, if we think about sustainability in that way, really everything we do becomes related to it. I really like the quote in Högfeld et al. (2023): “If [making connections to sustainable development] is not relevant for the … project, if it doesn’t have any economic aspects, ecological aspects, or social aspects, then why are [the students] even working on it?”. Sustainability is relevant everywhere, we just need to point it out!

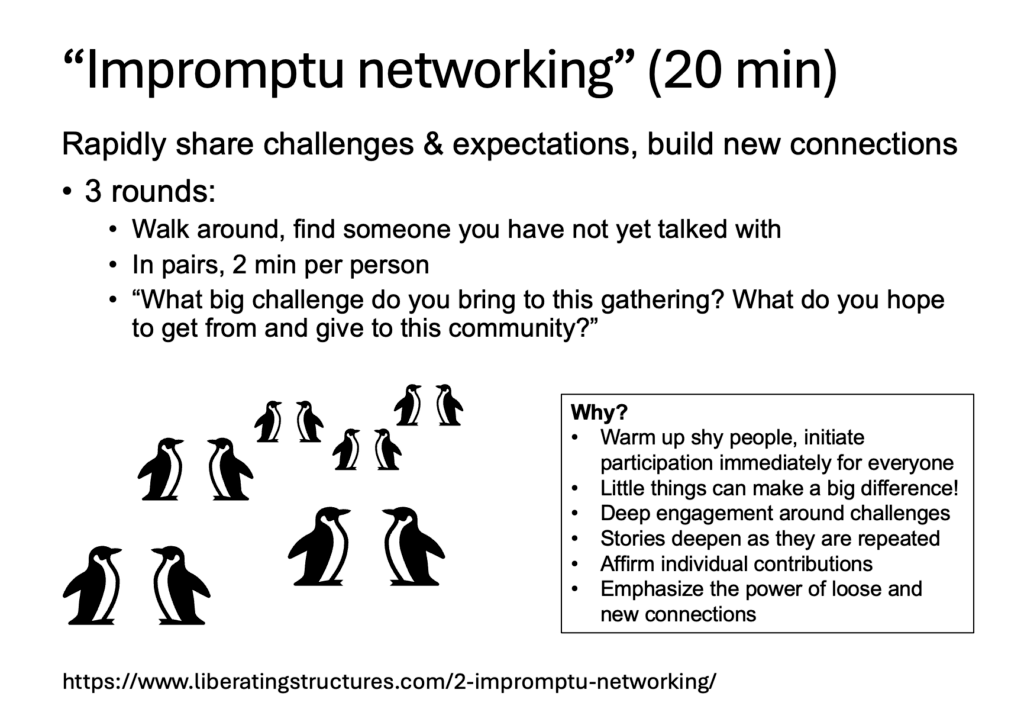

But so what is it that I mean when I talk about “teaching for sustainability”? To me, there are different facets to this, which I tried showing in the image below (and I only came up with this last week, so happy to get feedback and suggestions for improvement here!).

As a quick overview, and I will elaborate on the individual points below: In my opinion, only a small part of what we need to do to teach for sustainability is typically visible, and that is that there is sustainability content (typically defined through the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and we know from literature and experience how to teach that), and sustainability competencies (we also know a lot about those, and how to teach them). But what is mostly invisible but needs to happen is normalizing conversations, and creating a classroom climate and norms that support equitable learning and expression. The latter one we also know how to do, but the “normalizing conversations” part is the difficult part, because it makes us vulnerable as people (or might feel that way). And lastly, the whole iceberg floats — is supported — by “inner development” that we as teachers need to do.

In the picture above, I checked off the points that I think “we” (meaning the international community, not necessarily me personally) know enough to be able to find reasonably good answers about what and how to teach. The two non-checked points I haven’t read about enough yet to be equally confident, but those are the areas where I am currently reading a lot. So maybe there is “enough” out there already, and I just have to read more!

But let’s go through the points individually.

Sustainability content

In terms of what content to teach, teachers probably don’t have a huge amount of flexibility in the short term, since this is what is mostly prescribed in syllabi. Sustainability content is described for example in the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and elaborated on in the learning objectives, so if your topic fits any of those, it’s nice to make that connection explicit. Or maybe there are examples that you can use that make the connection more explicit. This is something that we need to look at for each course individually (and of course also relating to a whole program), but it is too individual to discuss more here.

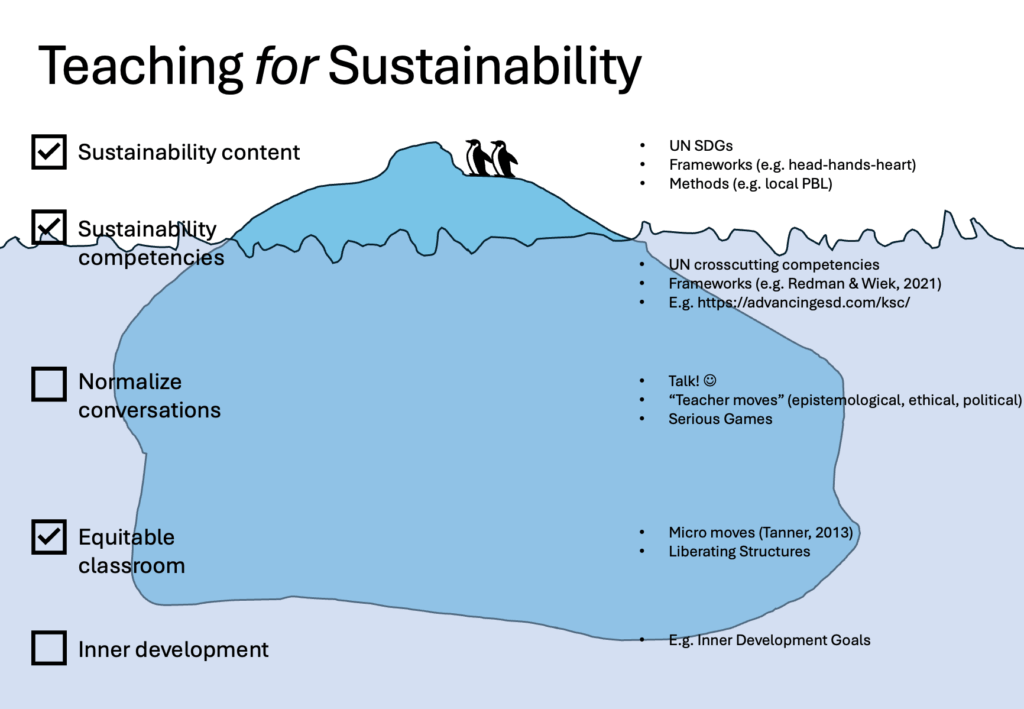

But we know how to teach sustainability content, there are several good frameworks, and I presented the head-hands-heart framework (see figure below). In a nutshell: For best learning, we need to engage not just the cognitive part of the brain, but also emotions and practical aspects. When I applied it to this specific course (read it in more detail here), I realized that I needed something with a bigger purpose that brought together all the reading and thinking and expertise with emotional connections in a community and the creation of some nice artifact, and the idea of opening up the fourth meeting to the wider community was born. It raises the status of the projects, makes them meaningful also as contribution to the community, gives visibility to engaged teachers, provides opportunities to connect with others; I don’t know why it only occurred to me now to do it this way (in contrast to an internal presentation), but at least it proves my point that the framework is actually helpful!

If you are curious about the poetry part: I mentioned my Science Poetry phase (check out examples here), and want to give a big shutout to all of Sam Illingworth‘s work on this!

I also quickly showed the bicycle model for climate change communication as a good alternative framework.

And we know what kind of methods work well: experiential, problem-based with links to local stakeholders. Lots of literature on that! And what that could look like for specific cases, we can explore together in the course.

Sustainability competencies

Here, I like to quote Wiek & Redman (2022): “While more momentum needs to be created in changing the educational practice and underlying drivers, from institutional support to individual responsibility, one aspect we feel compelled to advise against: no more reinventing competencies in sustainability! There is so much work to be done to make the practice of sustainability education more effective and efficient, before running out of time, that all of our collective effort should shift there. The existing convergence on a framework of key competencies in sustainability problem solving seems sufficient for moving forward on advancing the educational practice that the well-being of people and planet depends upon, at least to a significant extent.”

We know enough about what the competencies are (and I like to go with Redman &Wiek, 2021), we “just” need to implement them into curricula and teach them. Inspiration on how to do that can be found for example at the website “Advancing Education for Sustainability“, and again, what that might look like for specific cases, we can explore together in the course.

Normalizing conversations

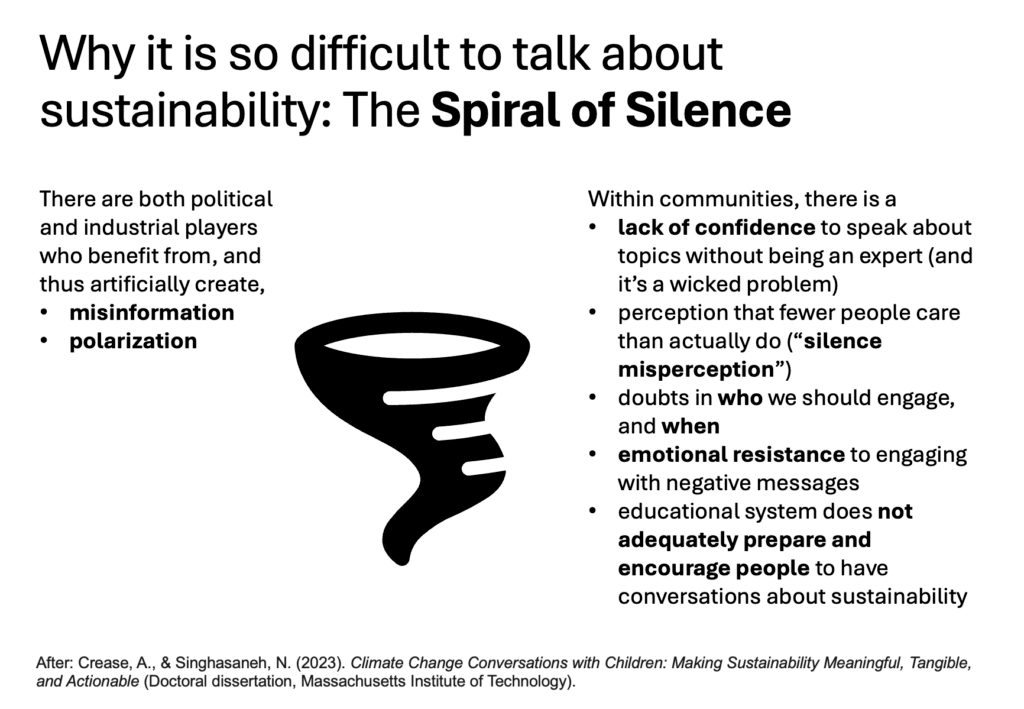

This, I think, is one of the biggest challenge: Just making it a normal and everyday thing to talk about sustainability topics. I found the “Spiral of Silence” (see figure below) in a thesis about climate change conversations with children, but I think it is a very helpful model in any case. The Spiral of Silence is really helpful to understand why it is so difficult to talk about sustainability:

There are political and economical reasons for many people to not want to have good conversations about sustainability, so there are powerful players that benefit from, and thus artificially create, misinformation and polarization, thus inhibiting conversations.

But also within communities, there are several factors that make conversations difficult:

- Many people (even teachers) feel that they don’t know enough to have conversations about sustainability. That is very relatable, but the problem is that it is a wicked problem, meaning that there is no one right solution, so there are also no experts that have a solution. Everybody has a lack of knowledge about some aspect, and we have to get over that and still engage in conversations, but be prepared to learn from each other or by ourselves

- The silence about the topic of sustainability makes it seem like it is not a topic that matters to people (because otherwise they would surely be talking about it?), but that is of course a vicious circle – if we don’t talk about it because so few other people are talking about it, what will encourage them to keep talking?

- This is maybe where the model is most clearly related to children, but people have doubts about who to talk to, and when. We don’t want to take hope for a good future away from children, or overburden them at a too young age, but also with students some teachers feel like “here, they should focus on learning x, and I want them to focus on that and not get caught up in despair or discussions that are beyond the scope of my course”. But of course at some point, someone needs to talk about it somewhere!

- But this emotional resistance to engaging with negative messages is a powerful obstacle to conversations, as is the

- educational system that does not adequately prepare or encourage people to have the conversations. But this is where we are working for change now!

I find this Spiral of Silence so helpful because it shows how complex the problem is. It is not just that there are players who don’t want us to talk about sustainability, even within us there are so many obstacles to overcome! But becoming aware is a good first step, and maybe reflecting on which of those (and possibly other) obstacles are relevant in our case. This is something we can then take up in our “inner development” (see below) and work on overcoming.

Of course, we also have ideas on how to do that. For example using Serious Games early on in study programs, or just as a standard asking at least three students to answer the same question, so that even if the three responses are essentially the same, we get used to listening to different people expressing things in different ways, and acknowledge that each of them is probably saying it in a way that some other people can relate more to than the other versions. Which leads us to creating an

Equitable classroom

There are so many things that we can do on different scales: For example using the Tanner (2013) equitable teaching strategies (that I have summarized here), or using Liberating Structures as I am doing in this session. Doing that, we can teach both about sustainability by explaining how the way we structure interactions can lead to the fastest and loudest person getting the most airtime, or making everybody’s ideas equally visible and having them being evaluated based on their value rather than on who brought them up. And of course, generally working for an inclusive classroom!

So much for what we do “in the classroom”. But then there is also our, the teachers’,

Inner development

And this is whre I am also thinking a lot right now, both for myself, and for how we can support and inspire each other in this. This is something that has to happen in community, but I believe there is also a lot of work to be done individually, to open ourselves to doing things like privilege mapping, and checking ourselves constantly for whether we are actually thinking critically and open to changing our minds if better evidence and arguments come along. In my iceberg analogy, this inner development and being a human in community is what provides buoyancy to keep the whole iceberg floating.

And at this point in the course, we needed a break (and luckily I had planned one).

After the break, we had to solve the puzzle of how to bring participants that all come with their own project idea into meaningful groups, so they can work together. Luckily, my idea for that worked out quite well: One by one, participants stood up and talked a bit about their project ideas, and then positioned themselves relative to the other ones that were already standing up; the closer the better the fit was with their own idea. And miraculously this worked out! And groups worked on their project ideas for some 45 minutes before…

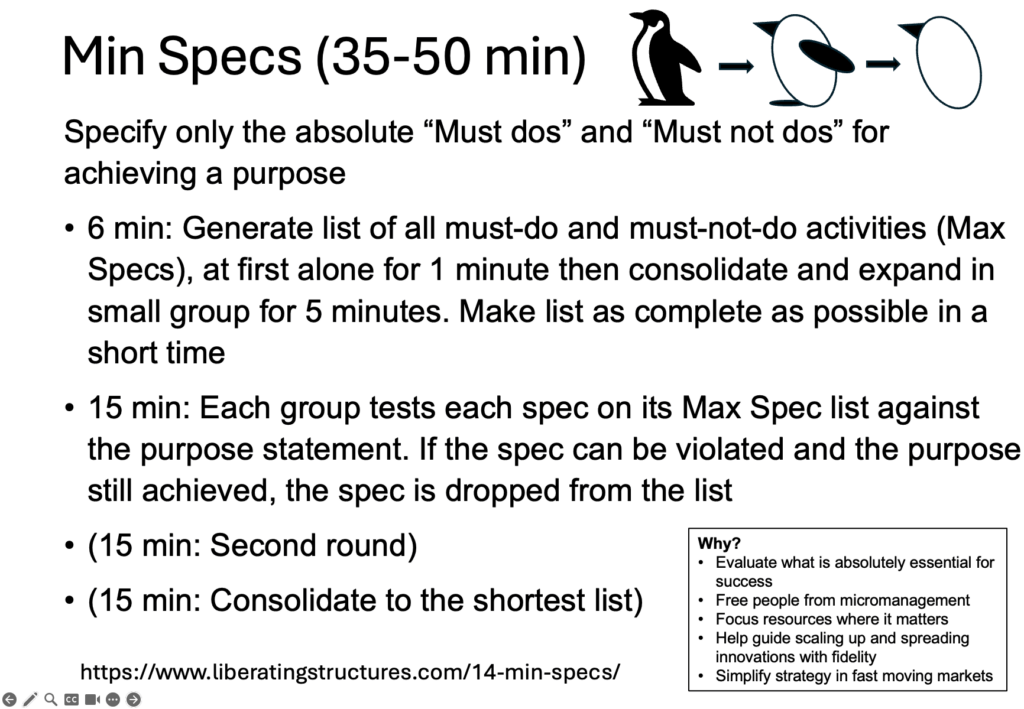

I introduced a second liberating structure: Min Specs (see picture below, and please note my visualization of a Min Spec penguin!). The purpose was to make sure their projects stay manageable — in a course that is “only worth” two weeks of credits, a lot of things can be achieved, but it is also important to stay realistic in order to not get too frustrated. One example for this is that the things that are really necessary for a successful meeting are a) communication about the time and place, and b) a shared goal, while things like an expert speaker, a detailed agenda, or slides are nice to have and often very useful, but optional. This is a very useful method!

So now we have a lot of great project ideas, and I cannot wait to see how they develop over time! But that is for the participants to report on at some later time, not me.

At this point, we were done with yesterday’s session, so lastly, about the featured image: Yesterday’s group in deep discussions. Note the name tents (read here about why it is always a good idea to use those! We even had post-it name tags because participants moved around a lot and I didn’t think it would be feasible to carry the name tents with them. I must say, I tried using post-its as name tags for the first time, and it worked surprisingly well!). Also note my coffee mug that I can now finally wash. I used coffee mugs to illustrate how sustainability topics can become very complex very quickly. We have this ongoing discussion about how to best cater coffee in our events. Single-use plastic mugs are out. But paper is also not a perfect alternative: Apparently it is also really energy-intensive to produce (and of course the paper needs to grow first, too, which needs area and water), and they are coated with something that is really toxic when it gets into ground water. Borrowing reusable mugs from the caterer seems an obvious solution, until they told us that they are legally required to use really strong industrial dish washing soap which is really also really not good, so they recommend as most environmentally-friendly alternative that we hand-wash, which we can do with less toxic soaps. But then this needs to be discussed in also a social context: Who does the hand-washing? Is it my job as the teacher, or do I put that task on our secretary, who also has other tasks to do but is in a weaker position of power? Or do we take turns between participants? Or does everybody bring their own mug and just washes them at home? That is probably the second best alternative for now, the best being demonstrated by my mug in the photo: Bring your own mug, but don’t wash! (Just kidding, obviously, it has been washed right after the course, I just brought it like that to make a point).

Wiek, A., & Redman, A. (2022). What do key competencies in sustainability offer and how to use them. In Competences in Education for Sustainable Development: Critical Perspectives(pp. 27-34). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Reflections on the workshop “How to deal with climate anxiety as teachers and researchers?” - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] vulnerable to social construction to silence” — see also my interpretation of the Spiral of Silence, I believe that is a very real problem!), and women are more likely to be anxious. But […]

#WaveWatchingWednesday - Adventures in Oceanography and Teaching says:

[…] Read more (and in a readable font size) here […]